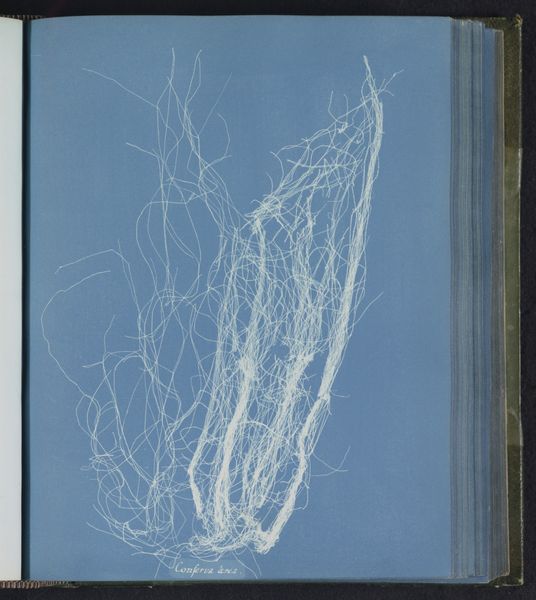

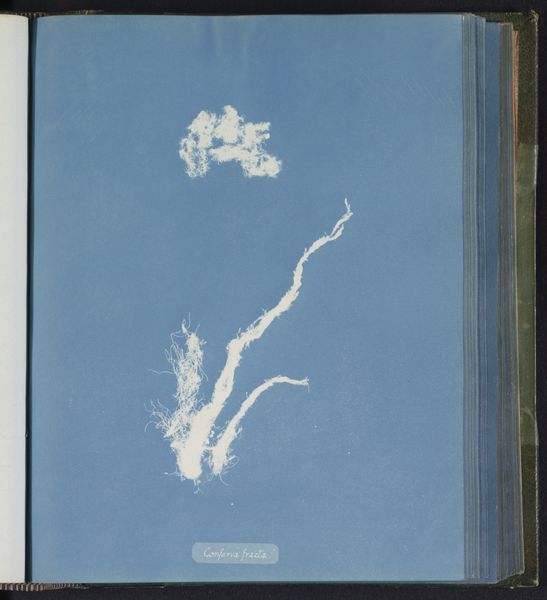

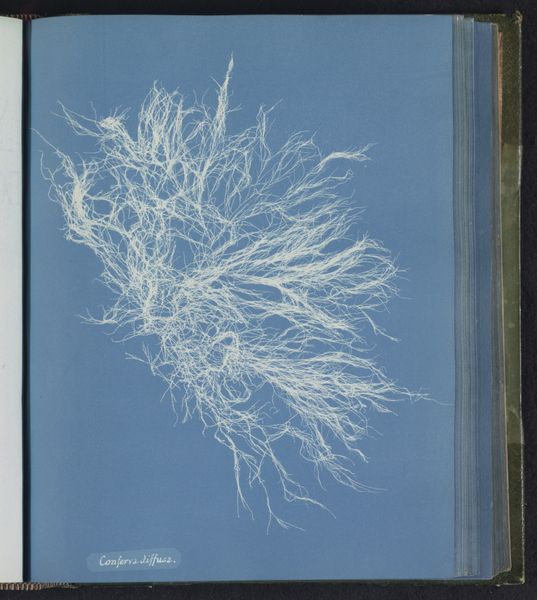

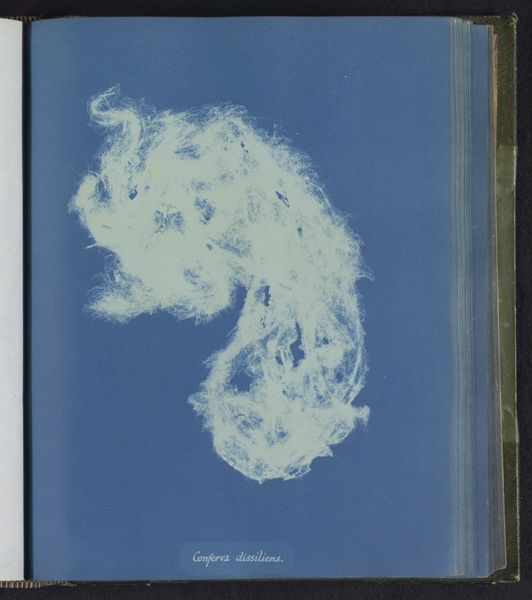

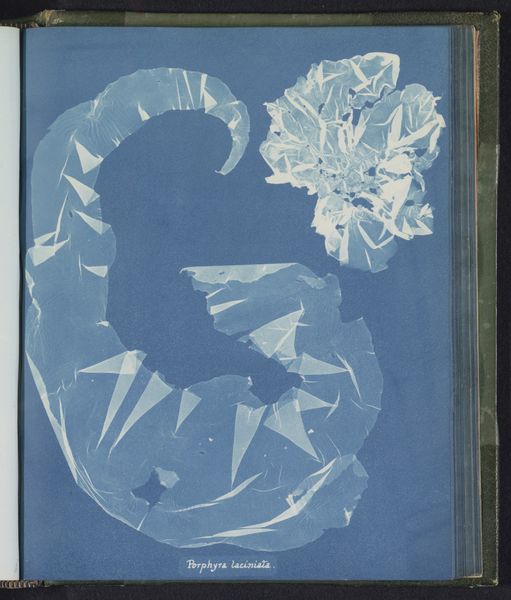

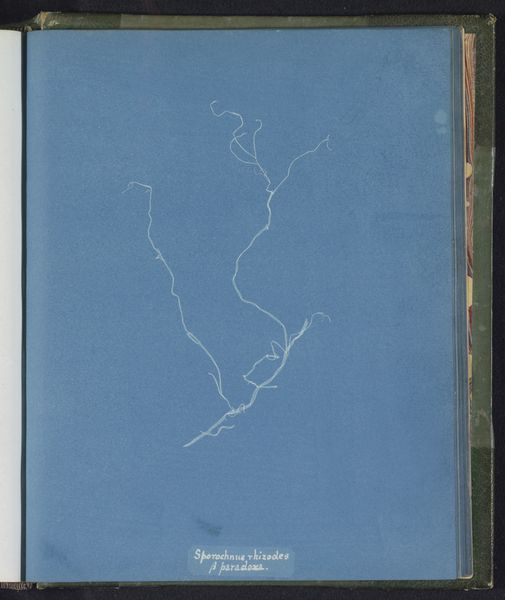

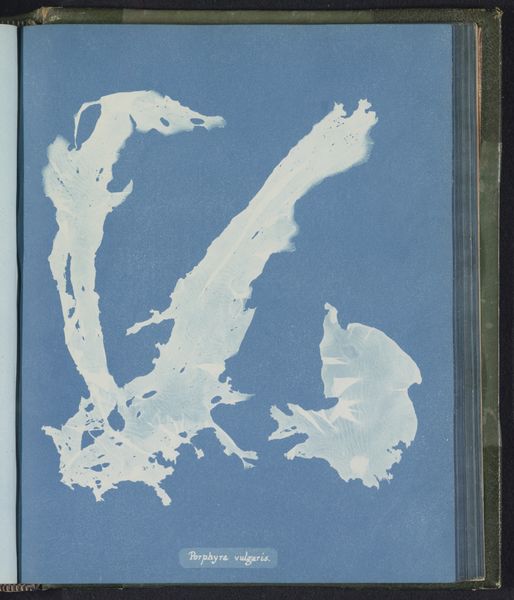

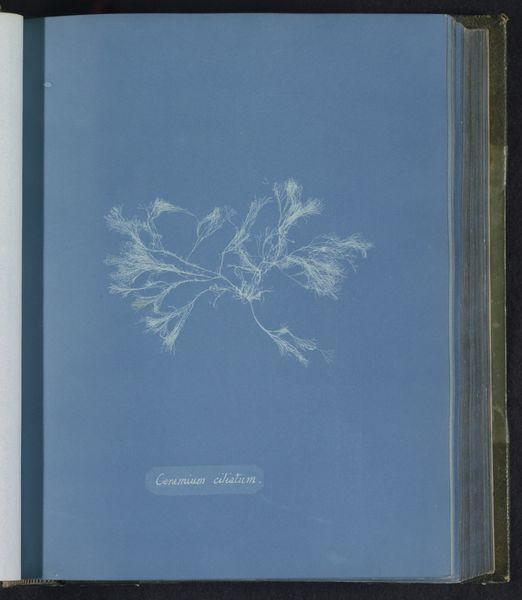

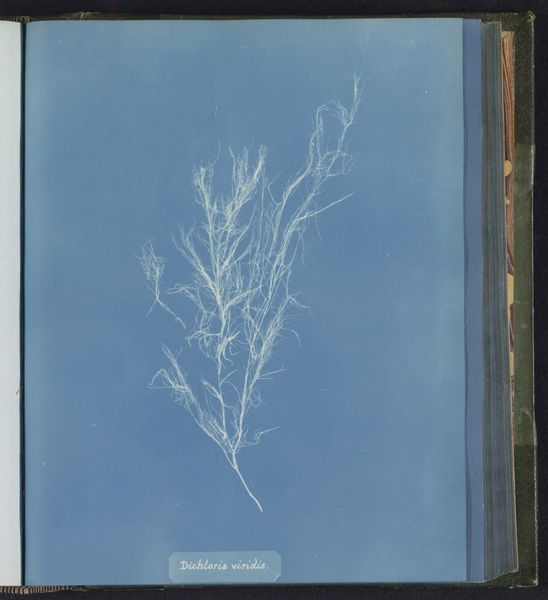

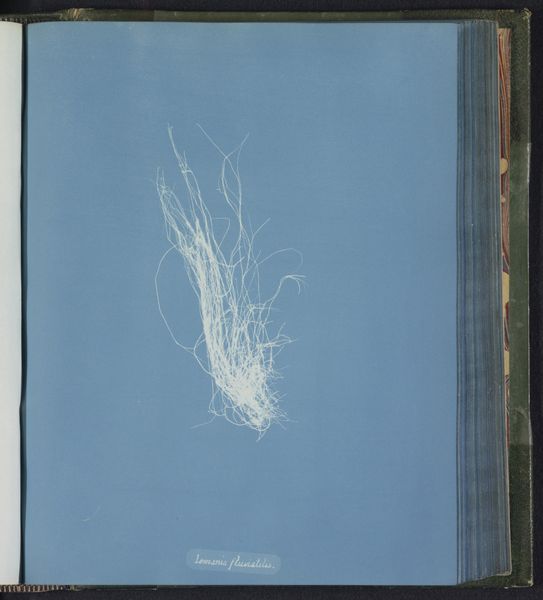

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

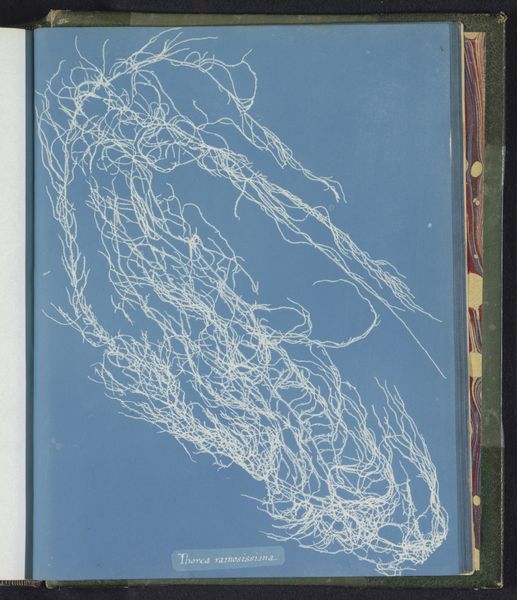

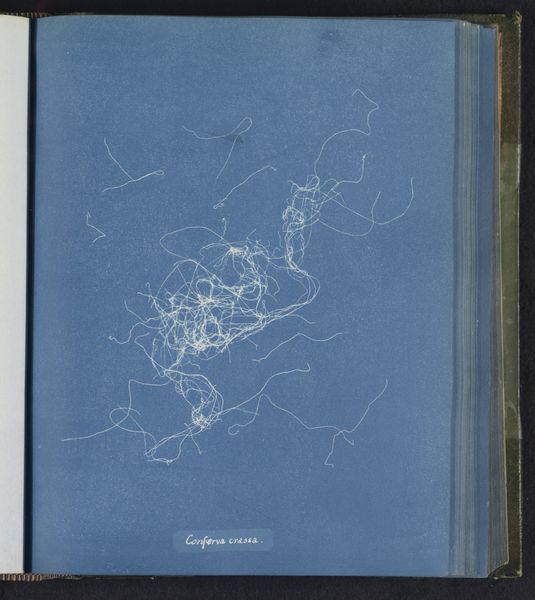

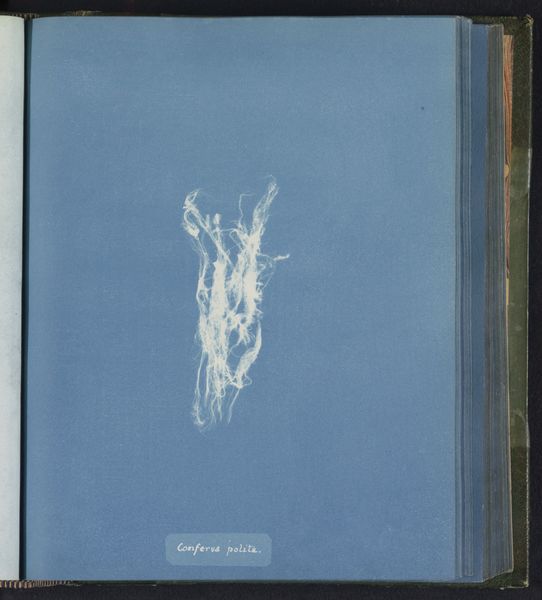

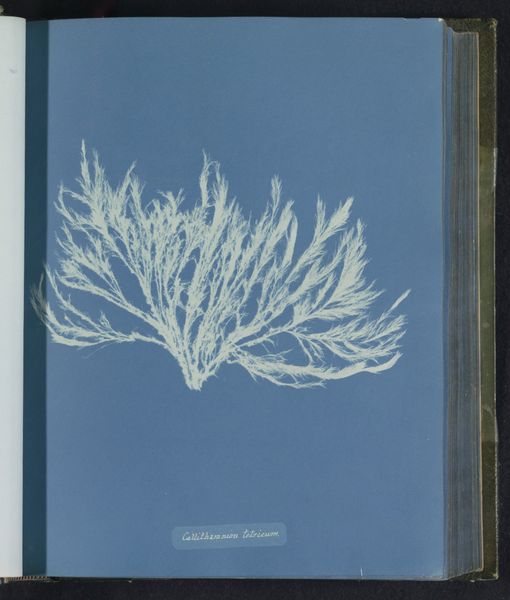

Curator: Looking at this image, one can't help but be struck by the ghostly quality, those translucent forms against that striking blue. It evokes a kind of dreamscape, or perhaps a scientific illustration filtered through an artistic sensibility. Editor: Exactly! This is a cyanotype, made circa 1843-1853 by Anna Atkins. She was a British botanist and photographer, and this image is from her series documenting algae – specifically, Enteromorpha intestinalis, a type of green algae. What’s truly radical here is that these works are considered some of the earliest examples of photography, period, especially by a woman. Curator: It is as much about her as about botanical classification! The choice of cyanotype lends the specimens an ethereal almost otherworldly quality. The plant life becomes symbols. Think of blue's long association with truth and fidelity; could Atkins be subtly commenting on photography’s claim to accurately depict the world? Editor: Absolutely. In the 19th century, museums and scientific institutions wielded significant power in shaping public knowledge and taste. Atkins, by choosing photography over traditional botanical illustration, engages with that power dynamic. These prints became part of a larger discourse about the authority of scientific representation. It begs the question of what power dynamics she would navigate today as a female scientist and artist in a contemporary cultural institution. Curator: I find myself thinking about the shadow self. We see these shapes as negatives. Does it speak to her experience of living in a certain social expectation of the time. She created her own rules using an exciting scientific approach. Editor: Cyanotypes, because of their accessibility, also democratized image-making to a degree. These allowed her botanical information to be shared broadly in the burgeoning scientific community. Curator: What endures is her unique sensibility; she sees her subject not as mere specimens but almost as portraits. These seaweed are ghostly apparitions with lives of their own, caught in her indigo dream. Editor: She bridges scientific pursuit with art history, leaving a lasting legacy and invites continued questions about representation and power that resonates powerfully even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.