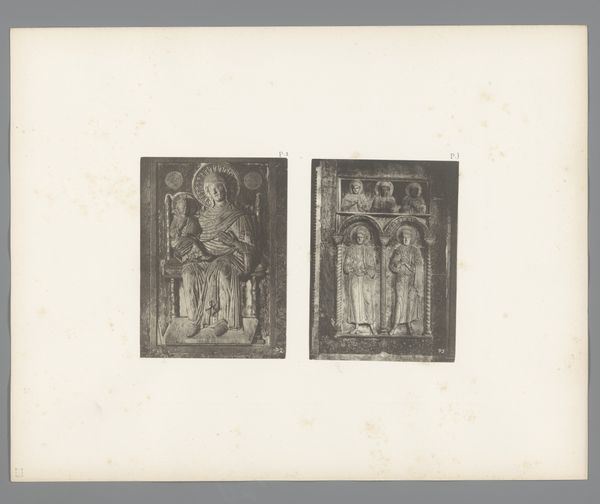

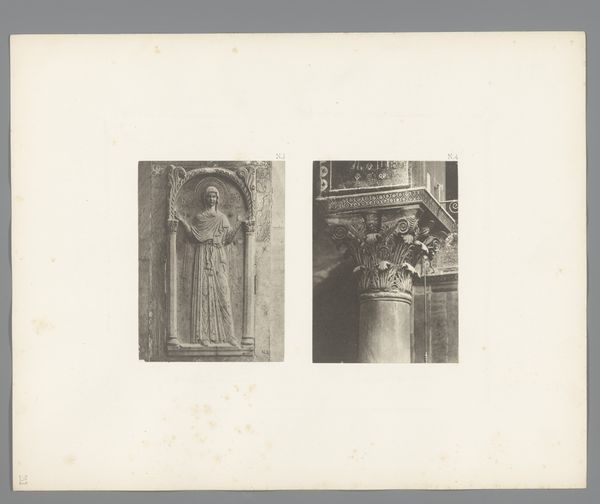

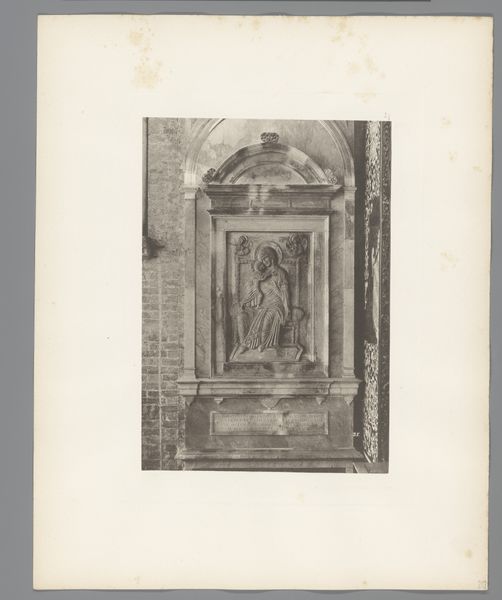

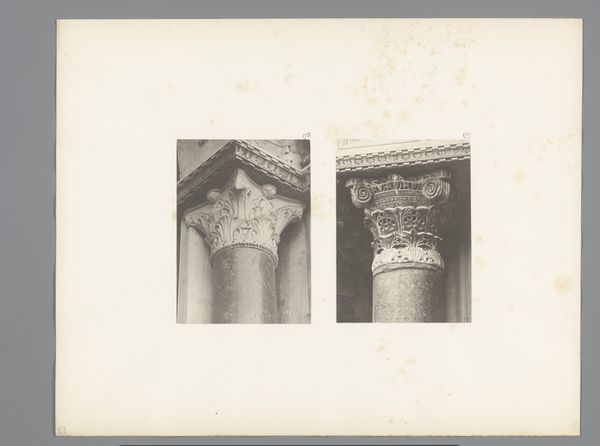

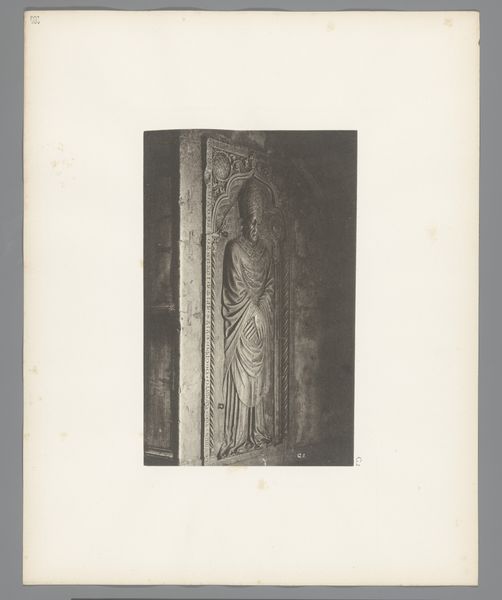

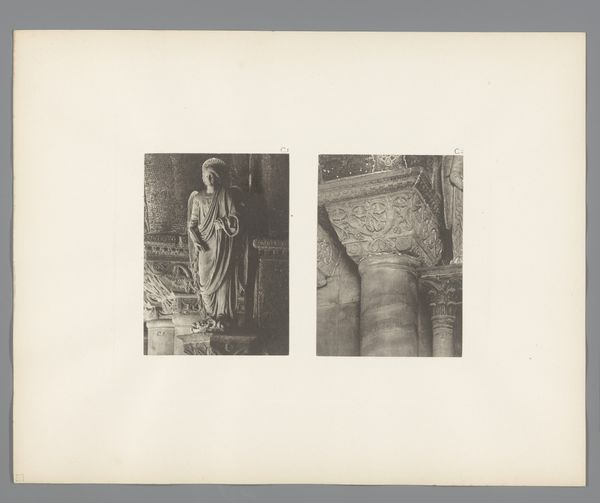

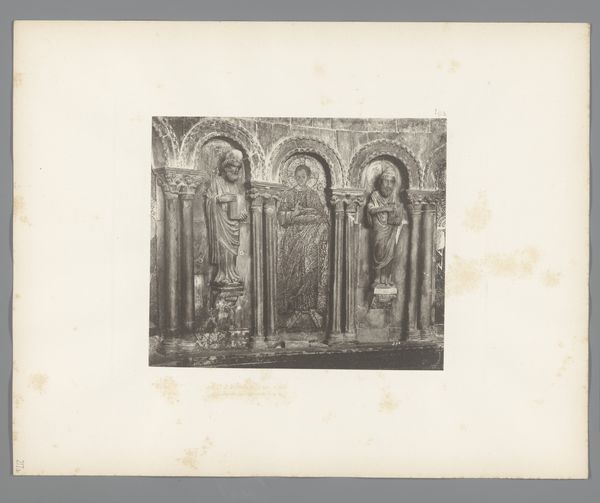

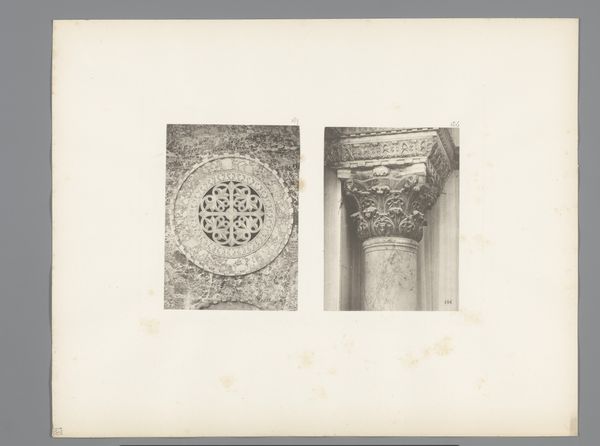

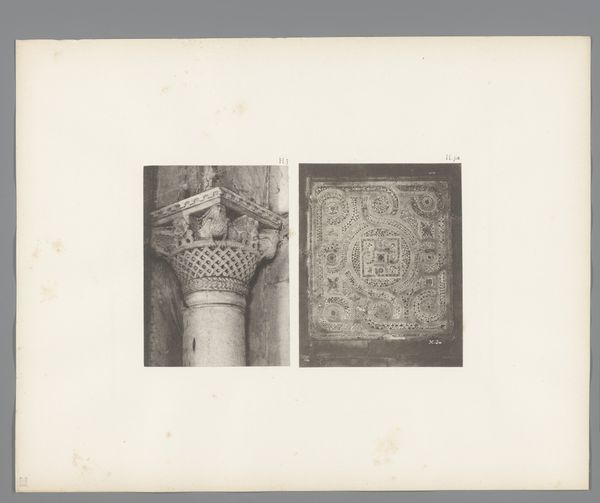

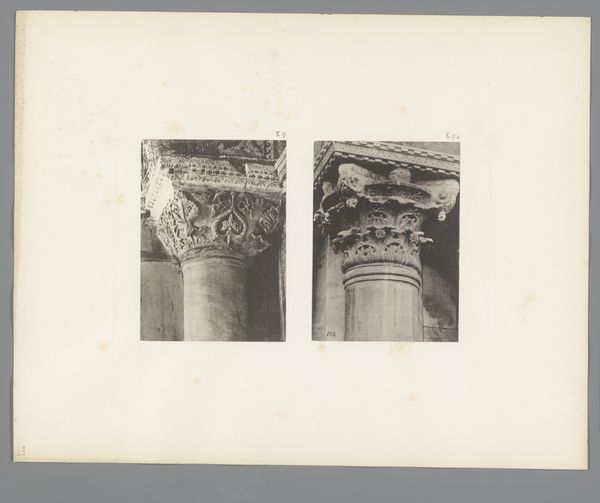

Reliëf van een heilige en een Korinthisch kapiteel van de San Marco in Venetië before 1885

0:00

0:00

print, relief, photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photo of handprinted image

#

still-life-photography

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

relief

#

classical-realism

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 311 mm, width 396 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this gelatin silver print, "Relief of a Saint and a Corinthian Capital of San Marco in Venice" by Carl Heinrich Jacobi, predates 1885. The composition is quite stark, presenting two distinct architectural elements. What strikes me is how photography, as a new means of reproduction, captured and disseminated these historical artifacts. What do you make of it? Curator: What I find compelling is how Jacobi's work highlights the evolving relationship between artistic creation and industrial processes. Before 1885, photography was increasingly democratizing access to art and architecture, breaking down geographical barriers to viewing relics. Think about the labor involved in creating the original reliefs and the Corinthian capital versus the relatively less intensive process of photographic reproduction. Editor: That's fascinating. So, you are focusing on how photography as a production method changes how art is consumed. Does the printing medium itself--the gelatin silver print—play a role here? Curator: Absolutely. The choice of a gelatin silver print—a relatively inexpensive and reproducible medium—suggests a move away from unique, handcrafted artistic objects towards mass production. Consider the social context. Who was this photograph intended for? Was it for educational purposes, documentation, or simply to satisfy a growing market for visual representations of European landmarks? These photographs become commodities. Editor: So, it's less about the artistic intention and more about the production, circulation, and consumption of this photographic print? Curator: Precisely. The image is interesting, of course. But focusing on the materiality and context illuminates a broader shift in art production and consumption in the late 19th century. What does it mean when religious iconography becomes so easily reproducible? Editor: This has really changed how I'm thinking about photography! Instead of focusing solely on subject, consider production processes as another interpretive angle. Thanks for shedding some light on this. Curator: My pleasure, thinking materially can yield so many exciting revelations!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.