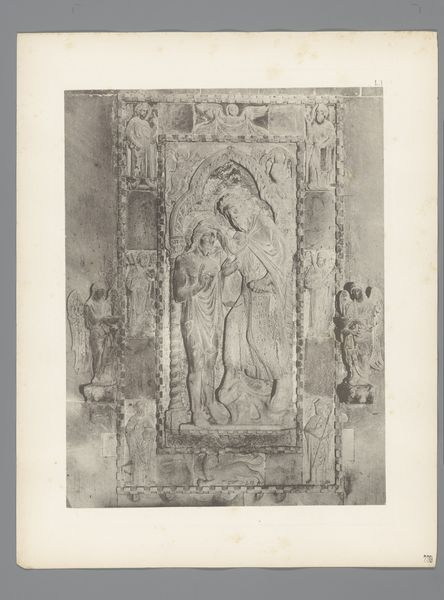

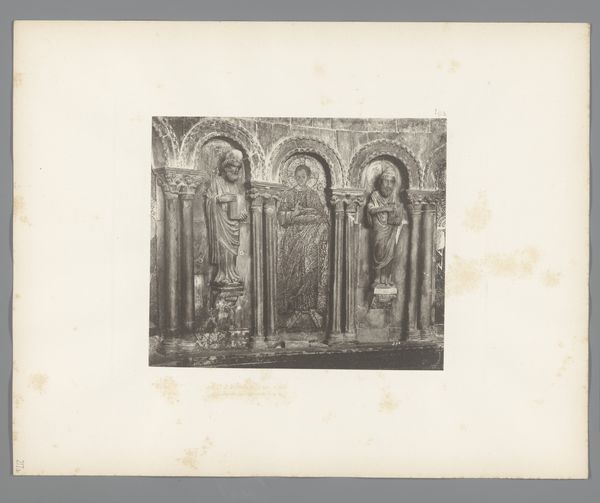

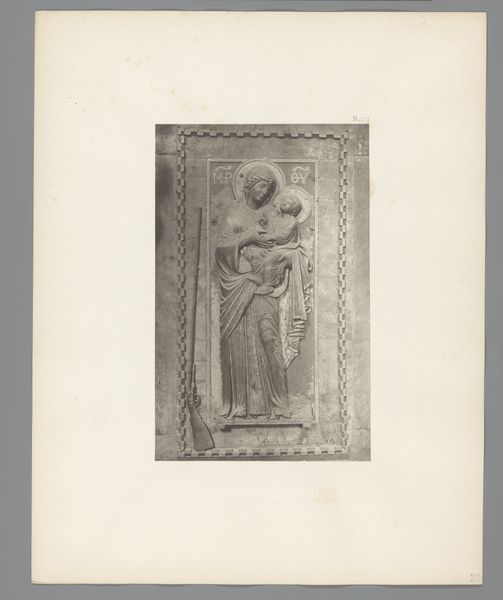

print, relief, photography, sculpture, marble

#

portrait

# print

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

relief

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

marble

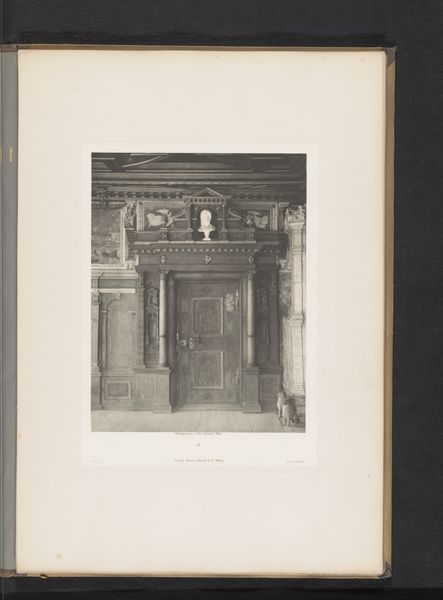

Dimensions: height 395 mm, width 313 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have a photograph taken by Carl Heinrich Jacobi before 1885, capturing a relief of Mary and Christ from San Marco in Venice. My first thought? How heavy, yet how graceful! The photograph renders stone almost ethereal. Editor: Heavy is right. You can practically feel the weight of the marble—its dense grain, the labor involved in extracting, carving, and transporting it all to Venice. It’s about materiality as much as divinity, right? The stone is speaking as much as the subjects represented. Curator: Exactly! And that interplay, the material whispering beneath the spiritual narrative, is so Venetian. There’s a real earthiness there too. Look at Mary’s pose; a mother holding her child—an intimate moment caught in solid rock. Editor: Marble’s not chosen lightly. Consider how sculptors often employed slave labor or were patronized by religious institutions who demanded displays of their material wealth and political dominance through objects like this. Curator: Indeed, a photograph mutes these contexts. Though it's about capturing history, perhaps smoothing away certain harshness, that’s often what light does; it allows for a kind of forgiveness in looking. That original, haptic reality—the cool, textured stone— becomes filtered, abstracted by the lens. We’re twice removed, then. Editor: The photographic print further flattens the three-dimensional form and renders even more ambiguous. Though intended as documentation, such images also transform an artifact of class and industry into a fetishized form of mass consumption. Curator: Well, looking at this now I’m struck by the enduring dialogue between human intention and natural elements. It began in a quarry long ago, then manifested into form. A kind of artistic alchemy continues—changing, changing, changing... Editor: Ultimately, that metamorphosis is one we as art historians play a role in, shaping its meaning for today and whatever conversations come tomorrow. Thank you, Jacobi.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.