#

comic strip sketch

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

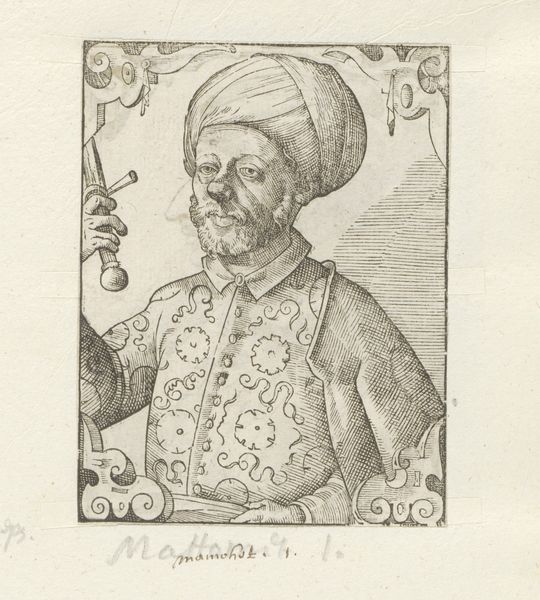

Dimensions: height 111 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We are looking at a sketch identified as “Portret van Ismail I”. Its creation is somewhere between 1549 and 1575, but the artist remains unknown. Editor: It looks like an official portrait, though the fine lines suggest that the purpose here was record-keeping rather than commemoration. I'd be keen to know more about the materials used. Curator: The work is rendered with delicate pencil strokes and showcases what appears to be old engraving techniques, emphasizing the subject’s regal bearing and the patterned turban. Note the controlled and subtle application of shading which describes form. Editor: Precisely. See how the density of line creates the illusion of different fabrics? I am very curious to understand how accessible these types of materials would have been. Consider the potential influence of location, workshop traditions, or the demands of artistic patronage on artistic creation and reception. Curator: Certainly, the interplay of light and shadow is masterful; the artist has employed cross-hatching to imbue the subject with volume, lending him a tangible presence, yet retaining the essence of linear grace, reminiscent of calligraphic precision. The ornamental details framing the portrait are meticulously drawn, indicating refined craftsmanship and attention to formal concerns. Editor: Looking at those minute details, I agree. But it begs the question, who would commission this sort of a work? Could this drawing function as a preliminary study, used for reproducing multiples or larger works intended to broadcast political imagery and ideals more broadly? Curator: An intriguing hypothesis! This emphasis on precision speaks to a broader context of 16th-century portraiture—one where symbolic weight and visual likeness had to negotiate one another on an individual level. Editor: I like that—negotiation! These methods point toward networks of exchange wherein resources and techniques circulated. It moves my attention away from a single creator to broader social conditions which made this form possible in the first place. Curator: Indeed. The work encapsulates how portraiture has acted as a repository for constructing individual, historical, and artistic identity in the early modern world. Editor: It underscores the power of making and distribution of that visual language, and for whom. Curator: Indeed. These qualities invite ongoing reflection about not just art history, but global history more broadly. Editor: A beautiful challenge, one thread in a complex textile of creation!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.