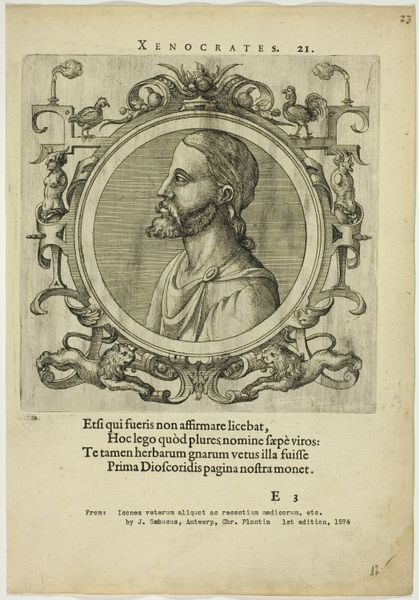

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 107 mm, width 83 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I'm struck immediately by the weight of the man's gaze, or rather, the fact that his gaze is averted. It imparts a sense of interiority, perhaps melancholy, right? Editor: Indeed. The artist here has presented us with what we believe to be a portrait of Christophe de Longueil. This engraving, dating sometime between 1549 and 1577, offers an intriguing glimpse into Renaissance portraiture. Curator: And note how contained he is! The decorative frame surrounding the subject—is that foliage?—almost seems to restrain his presence, reinforcing that inward focus. What does the frame evoke in you? Editor: I see a very deliberate act of commemoration and idealization at play. Framing a figure like this immediately elevates his status. Look at the architectural elements combined with natural motifs, a symbolic gesture towards enduring legacy. We have a kind of Renaissance architecture enclosing a fleeting moment of human experience. Curator: Yes, and this is further amplified by the geometric lines of his clothing sharply juxtaposed with the curving designs of the frame, providing us a subtle visual cue, speaking to a deeper cultural order. Note also the book he holds. I find its presence especially compelling, implying his access to the sacred, his potential for self reflection through scholarship. It lends itself to a certain mystique that resonates through history. Editor: It does indeed. The very act of reading and learning was imbued with significant cultural power during the Renaissance. And that leads me to wonder, what narratives and social forces propelled such portraits into existence, ensuring that particular likenesses of certain figures—mainly elite males, of course— were preserved for posterity. These types of portraits weren’t only depictions, they also dictated access to visibility. Curator: So you feel these symbolic elements like the frame and book helped ensure Longueil’s social endurance? They served to actively construct memory and bolster an elite image of the time? Editor: Precisely. Images can operate as active political instruments, participating in power relations, long after the subject themselves has disappeared. What is history if not iconography, arranged and memorialized? Curator: Well, it seems to me that art of this caliber leaves a layered tapestry. It enables us to examine those forces, acknowledge cultural imprints, and more fully come to terms with how we actively imbue images with symbolism over time. Editor: I agree. By questioning visual histories we unlock conversations and reclaim diverse, multiple interpretations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.