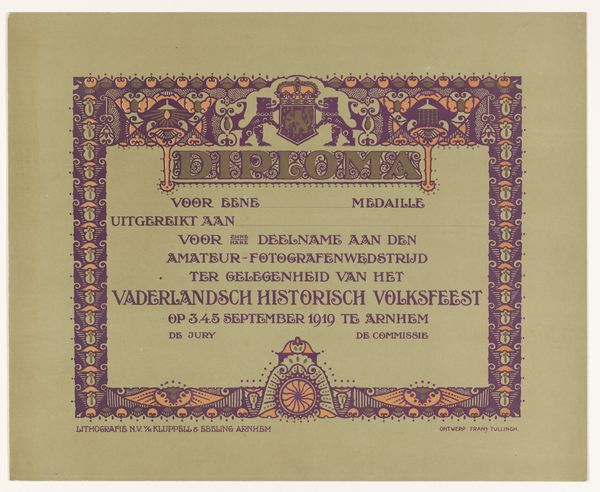

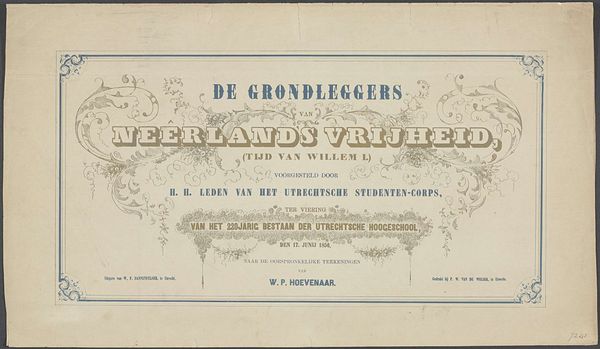

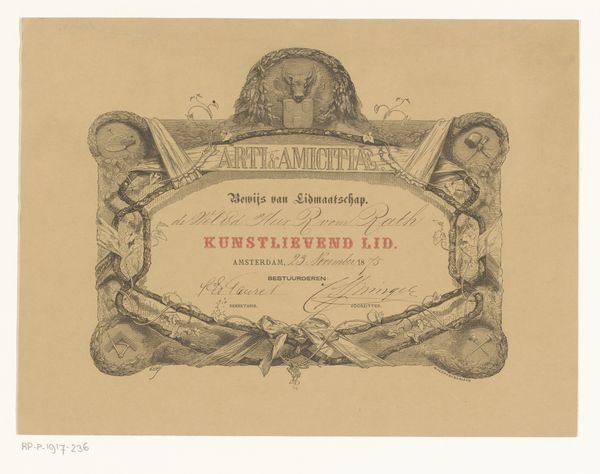

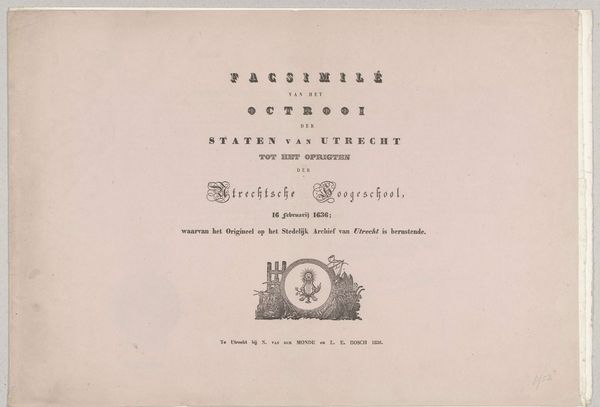

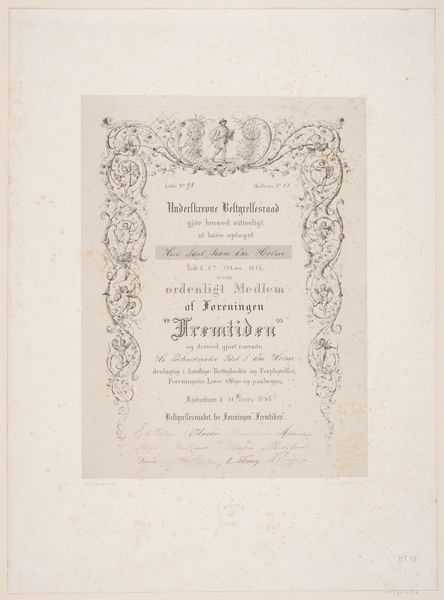

De Vaderlandsche Geschiedenis. van de vroegste tijden tot op het einde der 17e eeuw, in acht taferelen, in costuum voorgesteld door H.H. Dtudenten der Utrechtsche Hoogeschool, den 25 Juny 1851 1851

0:00

0:00

pieterwilhelmusvandeweijer

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print, typography

#

graphic-art

# print

#

typography

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

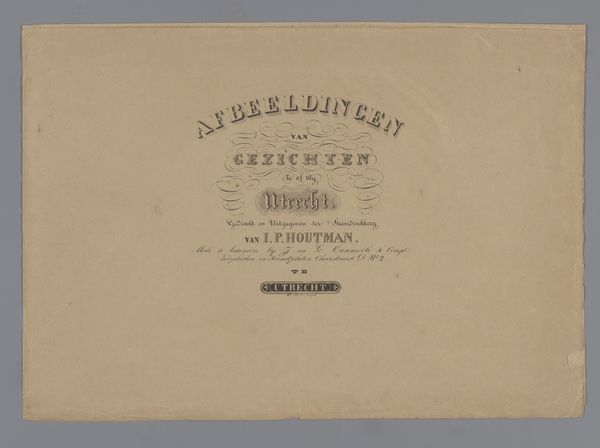

Dimensions: height 477 mm, width 620 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

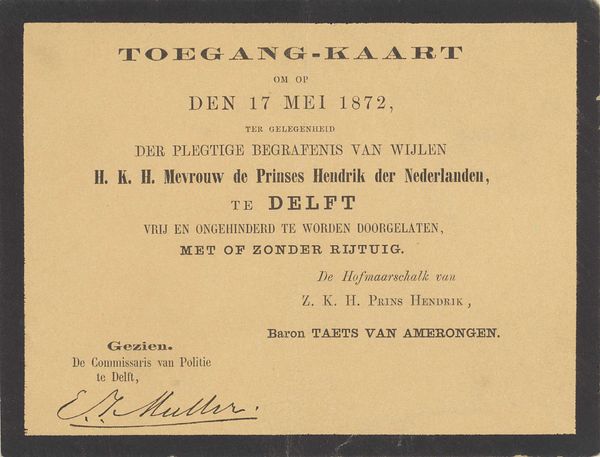

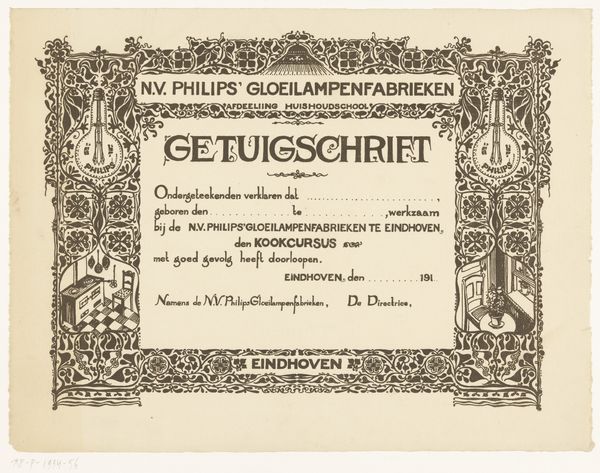

Editor: We're looking at a fascinating print called "De Vaderlandsche Geschiedenis…", which roughly translates to "The History of the Fatherland," created in 1851. It's typography and graphic art. At first glance, it seems like an invitation, maybe to some kind of historical performance? What do you make of this piece? Curator: It absolutely sings with the pride and flourish of the era, doesn’t it? Look closely – it’s an invitation, a souvenir even, documenting a specific event: a costumed historical presentation by students in Utrecht. These weren't just any students but those "H.H. Studenten", likely meaning highly esteemed or honorable students, presenting history through theatrical "tableaux vivants" – living pictures. You see echoes of that era in the careful ornamentation and that beautiful if somewhat formal, typography. It reminds me of a perfectly orchestrated parlor game designed to ignite patriotic sentiment! Do you feel that connection to its time when you look at it? Editor: I do see that performative, almost theatrical element. But why commemorate a student play like this? Was national pride a particularly hot topic then? Curator: Precisely! The 19th century saw a surge in national identity. Think about it: unified countries were taking shape, seeking to solidify a shared past, a common "history." This wasn't merely about remembering history; it was about shaping a collective memory. Imagine, students re-enacting key historical moments – that’s incredibly powerful in building a sense of national belonging. Plus, it probably looked splendid! A little like the historical re-enactments one sometimes sees at historic sights even now. Editor: So it's both a record of an event and a piece of propaganda, in a way? Curator: I wouldn't use such a loaded word. Think of it more as a carefully crafted articulation of a specific national narrative – an image promoting collective memory during a nation-building period. Editor: Interesting. I'll never look at student productions the same way again. I learned more about Dutch history by considering how it chose to celebrate it. Curator: Me too. Seeing something in such context often tells us so much more than its literal content ever could.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.