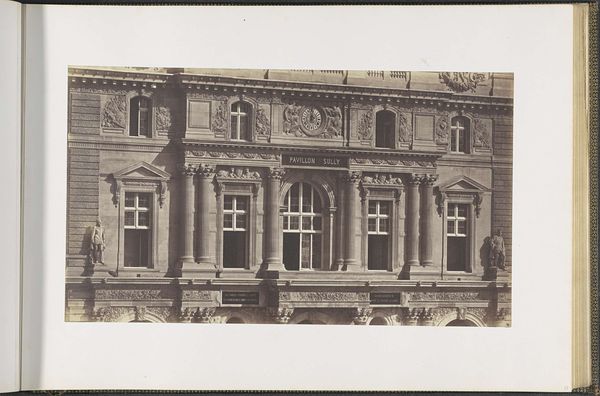

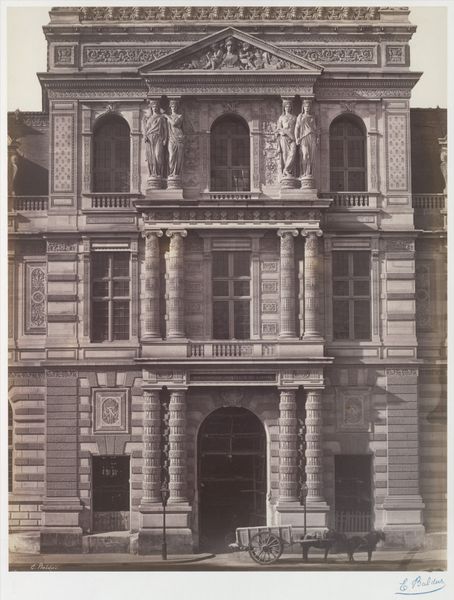

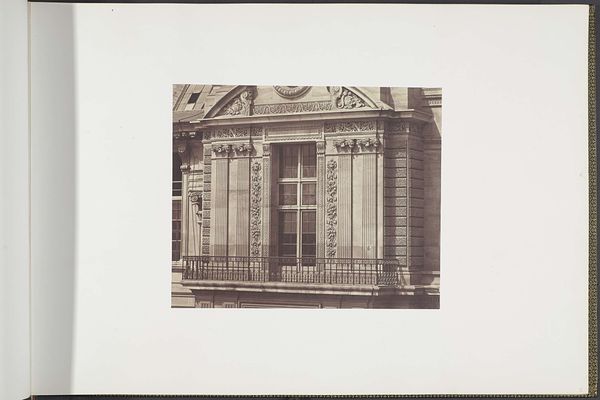

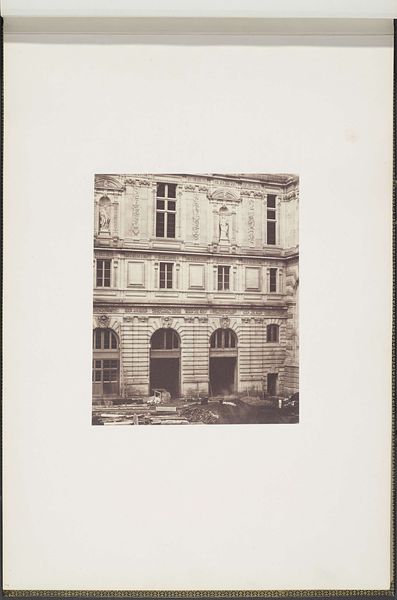

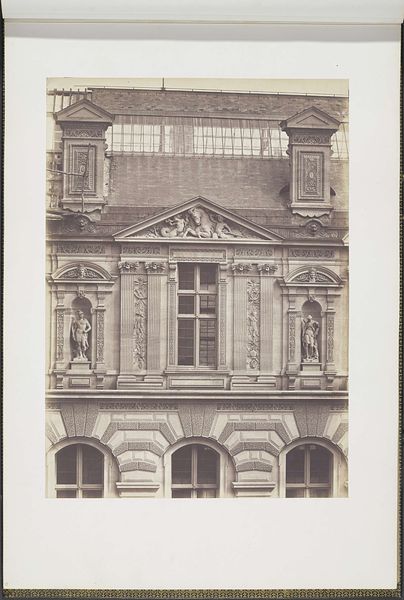

Eerste verdieping van het Pavillon Richelieu in het Palais du Louvre c. 1857

0:00

0:00

edouardbaldus

Rijksmuseum

photography, albumen-print

#

neoclacissism

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

#

building

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 556 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

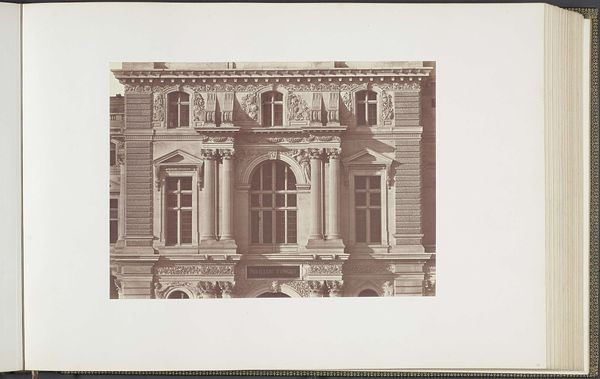

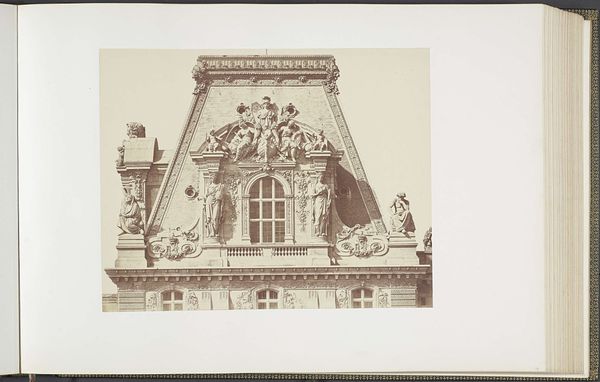

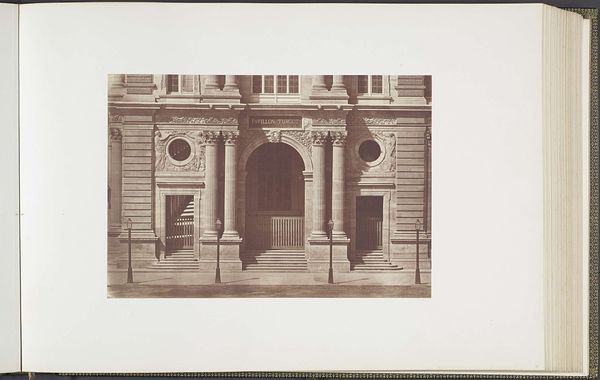

Editor: So, this is Édouard Baldus's albumen print, "First Floor of the Richelieu Pavilion in the Palais du Louvre," circa 1857. It’s a close-up of the Louvre's facade, very symmetrical and…stately, I guess? What's striking to you about it? Curator: What I find powerful is understanding the photograph within the context of its time, particularly France under Napoleon III. Think about the urban renewal projects of Haussmann, which drastically reshaped Paris. This photograph, in its almost clinical depiction of neoclassical architecture, becomes a document, a witness, even an instrument of power. How does this "stately" facade speak to the socio-political agenda of the time? Editor: So, you're saying it's not just a picture of a pretty building; it's about…control? The order feels very deliberate. Curator: Precisely. The Louvre wasn’t just a museum; it was a symbol of French identity, power, and cultural dominance. Baldus's precise rendering, the stark clarity, was intended to project an image of stability and permanence, solidifying the Emperor's vision of a renewed and "improved" France. Think about who this image was meant for – not necessarily the common citizen. Does that shift how you interpret its symmetry? Editor: Definitely. Knowing the social context changes everything. I initially saw it as beautiful architecture, but now I recognize that it tells a much larger story about class and power. Curator: It’s also vital to note how photography, still in its relative infancy, contributed to legitimizing those in power. Consider its documentary function during colonization and industrialization; consider those unseen and unphotographed. Editor: Wow, that really gives me a lot to think about, considering the layers of historical context, and what remains hidden. Curator: Yes, and hopefully, the way we engage with historical imagery is to continuously question and unearth those untold stories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.