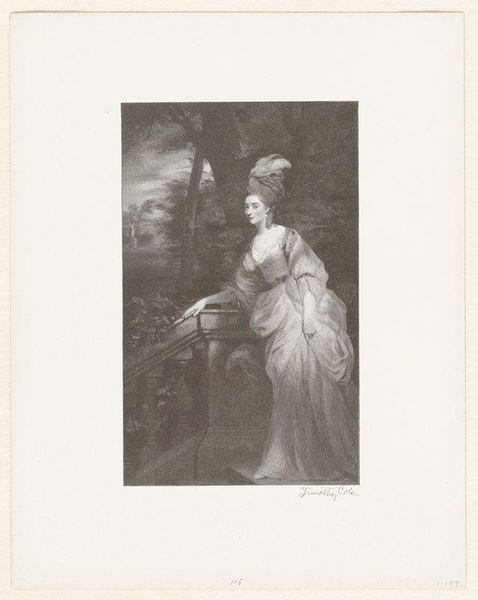

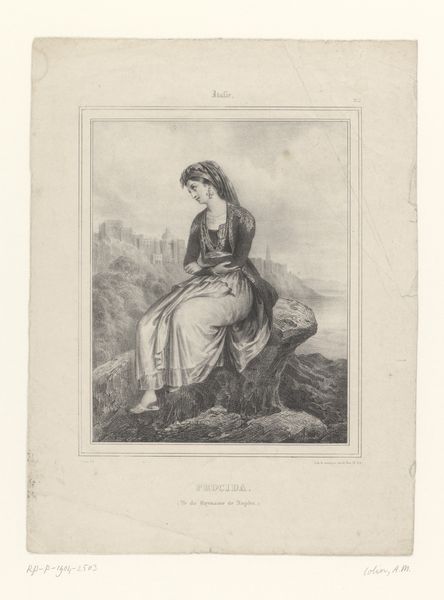

drawing, lithograph, print, paper

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

united-states

Dimensions: 254 × 200 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

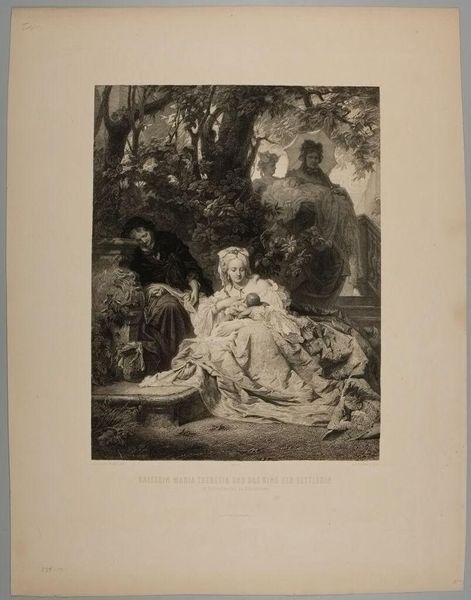

Curator: "Portrait of Mrs. Henry Inman," a lithograph dating to 1831, captivates with its romantic essence. Let’s delve deeper into the history and cultural implications embedded within. What are your initial impressions? Editor: I'm struck by the air of melancholy. She seems to be caught in a moment of introspection, set against a backdrop that almost feels like a stage for her solitude. Curator: Absolutely, the placement is strategic. Inman was an astute businessman-artist, carefully cultivating his social standing, often through such portraits that acted as endorsements between prominent families in burgeoning urban centers. Her delicate features rendered in lithographic perfection ensured not just a likeness, but an aspirational image, circulated widely. Editor: That commercial aspect is key, but what stories lie hidden within her gaze? Is she merely a symbol of her husband’s success, or can we glimpse a deeper, perhaps unfulfilled, identity? The romantic landscape, while idyllic, almost boxes her in, doesn’t it? It suggests constraints, even as it emphasizes beauty. Curator: These are essential tensions to consider. The picturesque landscape, popular in romanticism, serves as more than just a backdrop, of course. It was carefully selected for its symbolic meanings: perhaps growth, perhaps virtue. We need to read these clues together to place Mrs. Inman within the proper aesthetic and social conversation. Editor: True. We have to think critically about the intersection of her individual experience and the constraints placed upon women, especially in the construction of an image, consciously designed for public consumption. Curator: And this print allowed broader access; these lithographs became cultural objects of the burgeoning middle class, keen to partake in sophisticated visual language previously afforded only the elite. Editor: I appreciate your highlighting that broader social reach, because this gives a real, visual language of aspirations to those excluded from art production and consumption. What may seem on the surface to be simply a portrait of an individual contains such dense ideological meaning about access and identity. Curator: Exactly. By studying this piece and acknowledging these dialogues, we unlock insights into gender dynamics, economic structures, and the evolving perception of art. Editor: A portrait that transcends the surface, offering a glimpse into America’s burgeoning identity in 1831, and maybe even the stifled dreams of a sitter long obscured by the shadows of both Romanticism and the art market.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.