photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

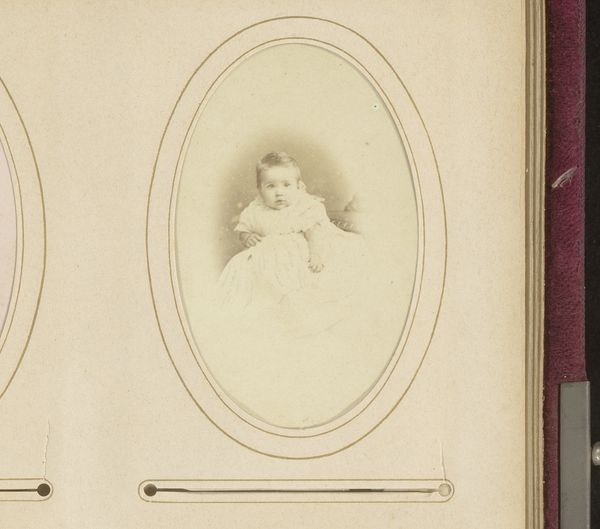

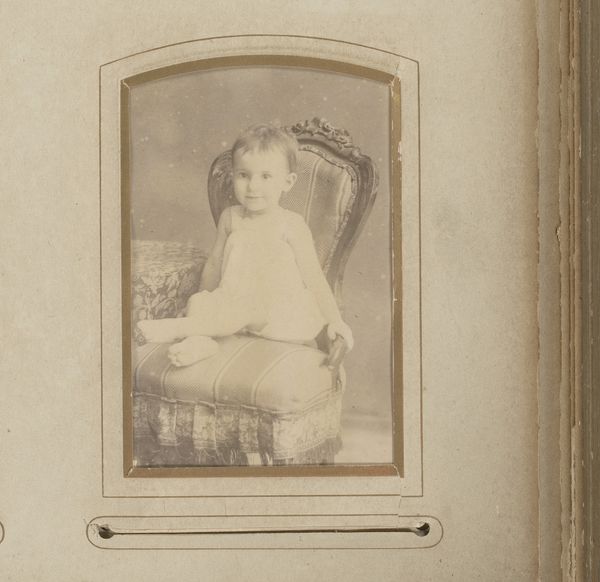

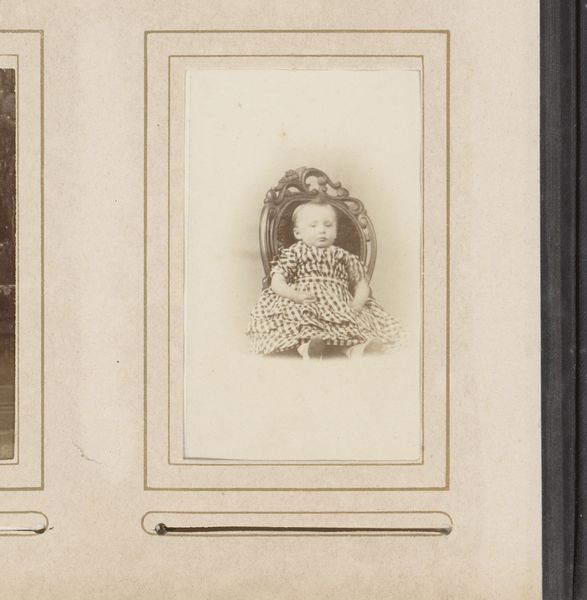

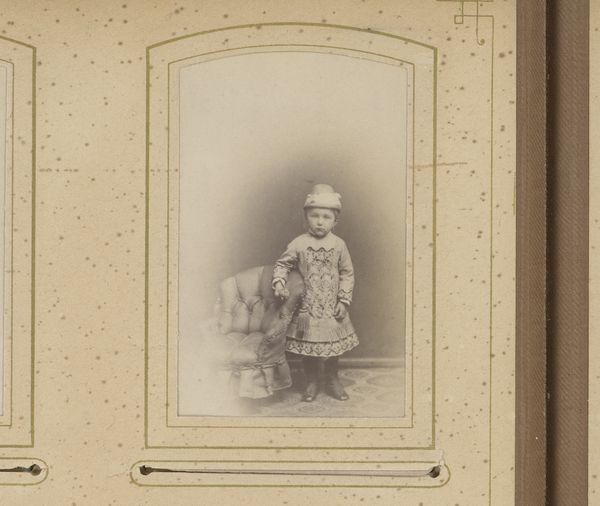

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This gelatin-silver print, "Portret van een zittend kind," created by Jean Günther between 1886 and 1890, feels very intimate. The photograph’s surface shows its age, creating an almost ghostly presence. What's most striking to you about this piece? Curator: What I find compelling is how this ordinary photograph illuminates 19th-century photographic processes and social customs. The labor involved in creating a gelatin-silver print – the preparation of the emulsion, the exposure, the development – it's all a stark contrast to our contemporary digital photography. Editor: So, it's the actual *making* of the photograph you find most significant? Curator: Precisely. Consider the social context. Photographic portraits at this time weren't casual snapshots; they were carefully constructed and posed, and represented a level of social status attainable through the consumption of photography. The subject's clothing, for example, speaks to the economic realities of the sitter's family. What's particularly interesting is the democratization of portraiture afforded by new printing technologies, while access was still demarcated by socio-economic forces. Editor: I hadn't considered the democratization aspect so explicitly. The child's pose and dress certainly indicate some level of social positioning, but against the backdrop of increasing access to photography. Curator: The damage on the print further complicates its reading, suggesting the effects of time and handling and material conditions which speak to our present moment, with the decline of traditional photography and archiving as consumption habits evolve. What does it mean to "save" photographs digitally, without tactility? Editor: This makes me think about our relationship to images today—how we produce and consume them so readily and whether that changes their meaning, and labor, completely. Curator: Exactly. Looking at this photograph through the lens of its material production reveals layers of social and cultural meaning, asking us to critically assess the art, value, and labour of images today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.