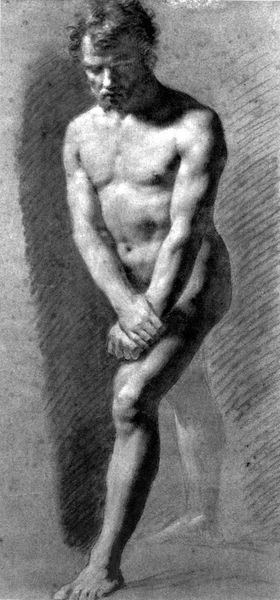

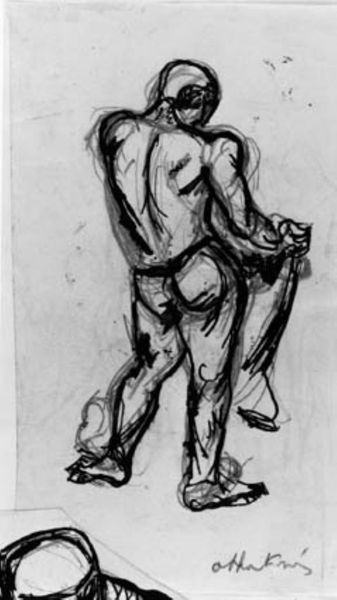

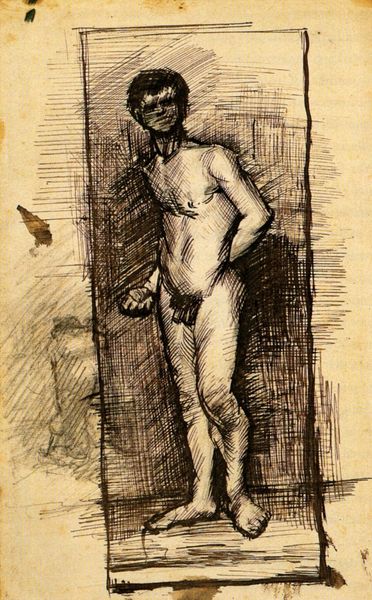

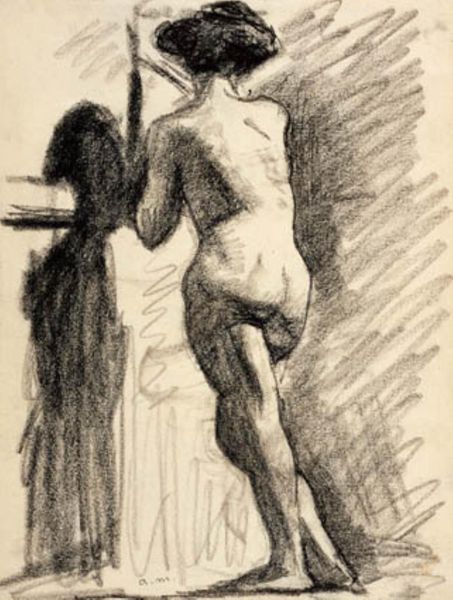

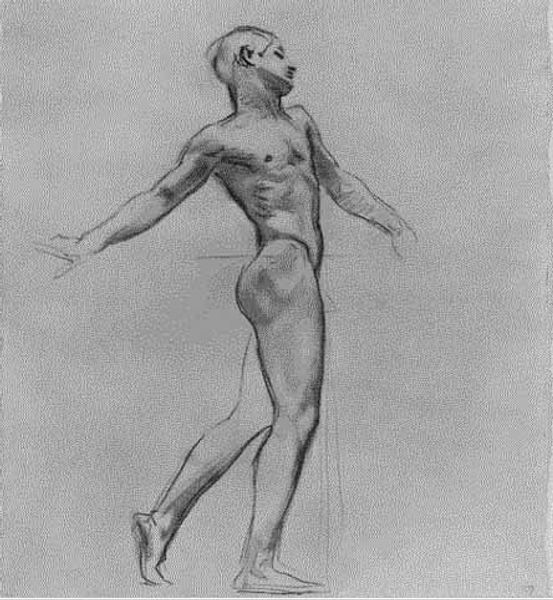

drawing, charcoal

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

portrait reference

#

sketch

#

charcoal

#

academic-art

#

nude

Copyright: Public domain

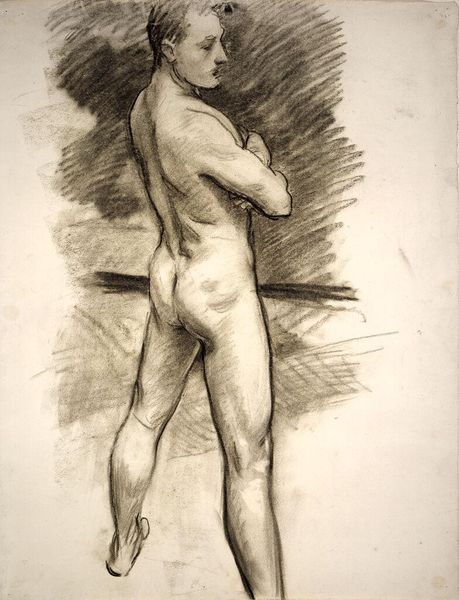

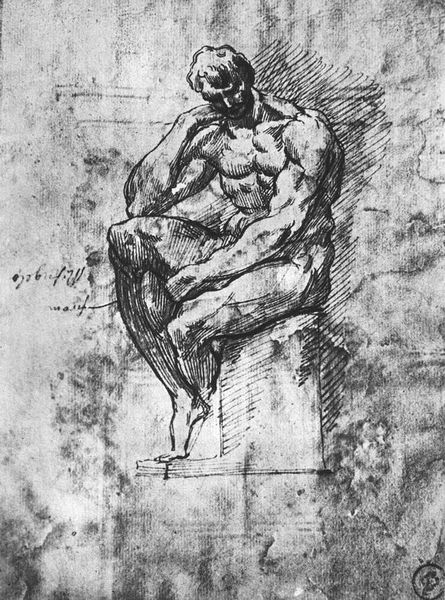

Curator: So, standing before us, we have a drawing—a rather stark charcoal drawing—entitled "Plaster Statuette," crafted by Vincent van Gogh in 1886. It's currently residing here, at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. Editor: The first thing that hits me is the figure's back—it’s powerfully rendered, even though it's just a sketch. There's this intense vulnerability, standing starkly against that roughly shaded background. It feels unfinished, almost yearning for something. Curator: Yes, "yearning" captures it nicely. You see, Van Gogh was deeply engaged with academic exercises at this time, diligently studying anatomy. This drawing reflects his rigorous approach to mastering form. It represents the start of Van Gogh exploring how to present the human body with both structure and emotions, which will later be more prominent in his own distinctive style. Notice, if you will, how light and shadow define the muscles. Editor: Absolutely, the hatching creates a striking three-dimensionality. But it’s also intriguing how he shrouds the figure's head in shadow. We lose any sense of individuality. Is it a conscious denial of identity, making it more of a symbol than a portrait? The pose seems classical, reminding me of ancient sculptures—almost stoic—but there's also this palpable sense of struggle, caught between ideal and reality. Curator: I think that's spot on. Academic studies such as this sought the ideal. The body as a temple, as it were. But what’s truly engaging here is the juxtaposition of that classical aspiration against Van Gogh's raw, expressive mark-making. He's wrestling with tradition, searching for his own visual language within its constraints. And perhaps that shadow serves to depersonalize, shifting focus to the universal human form and its potential for emotional expression. Editor: It also underscores the constant dialogue with historical images. The enduring effort to relate to this symbolic past that somehow survives, reworked, into a new symbolic vocabulary. The fact that is unfinished somehow strengthens that for me; as a reflection on the present moment as just an evolving piece of the whole. Curator: Agreed. I find it quite moving to consider it a meditation on how we always exist in dialogue with that "symbolic past" as he forges his own visual style, searching for meaning both within and beyond established norms. Editor: A poignant point. Well, I’m walking away considering not only how we view, but what is, classical symbolism, and what part our perspectives take in the continuing dialogue that these images promote.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.