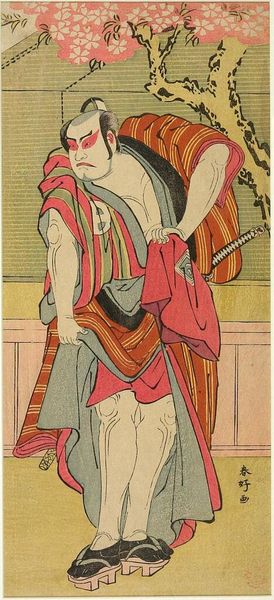

Kabuki Actor Bandō Mitsugorō III as Katsura Kokingo Haruhisa in the Play Uruō Toshi Meika No Homare 1795

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public domain

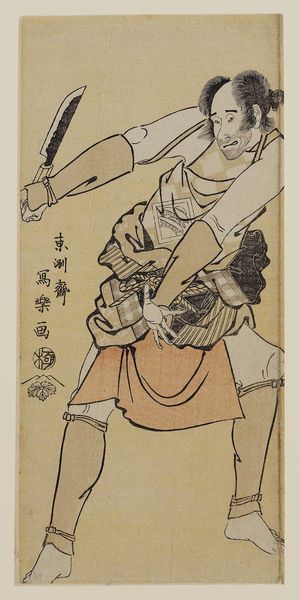

Curator: Here we have Tōshūsai Sharaku's woodblock print, "Kabuki Actor Bandō Mitsugorō III as Katsura Kokingo Haruhisa in the Play Urod Toshi Meika No Homare", created in 1795. Editor: My first impression is one of somewhat unsettling tension. The figure's posture is so stiff, almost defiant, yet the muted colours give it a strangely aged feel. Curator: Absolutely. Sharaku was a master of capturing the essence of his subjects. Note the actor's piercing gaze; it speaks volumes about the character he's portraying, even for audiences today. He seems trapped in a role. Editor: This tension is echoed in the broader social context. Kabuki at the time was very popular, yes, but it also faced societal criticism for perceived moral corruption. Viewing kabuki actors as role models also sparked discussion about cultural impact. How were these performances shaping popular morality and what kind of values were being reinforced, intentionally or unintentionally, through these theatrical portrayals? Curator: The symbols are also significant, I feel, in unlocking a cultural story, for instance, we see the gate structure behind the actor that resembles bamboo and rope designs. Those represent strength and purity but may simultaneously symbolize barriers and restrictions for the artist and/or the actor. Editor: Right, and I see a commentary on artistic identity. Sharaku's work often reflects the ambiguous position of the artist in society – celebrated, but perhaps also viewed with suspicion for revealing potentially challenging aspects of humanity. Note the almost cruel, cynical depiction of humanity that is being communicated with this artwork. Curator: Furthermore, the "ukiyo-e," or "pictures of the floating world," style captured the fleeting moments of pleasure and entertainment, and a world of impermanence that echoes Buddhist philosophy. Editor: Ukiyo-e definitely offered escapism. However, the themes weren't always frivolous. It’s important to remember these prints often reflect very real social hierarchies and dynamics. Consider how the exaggerated expressions used by Sharaku in portraying his kabuki characters invite us to reconsider their role. How do their individual identities fit within the confines of performative representation? Curator: I find myself questioning what these artistic images teach me about Japanese history, identity and human emotion. The legacy of the Ukiyo-e woodblock endures because, across different art forms and periods, its capacity to engage complex topics remains palpable. Editor: Definitely, it brings forth not just cultural meanings of historical Japanese culture but extends them beyond this specific cultural milieu. The capacity to convey meaning, to make visible an underlying social commentary that still feels relevant today, confirms why these artworks endure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.