Dimensions: 9 9/16 × 7 7/16 in. (24.29 × 18.89 cm) (image)13 3/4 × 10 11/16 in. (34.93 × 27.15 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

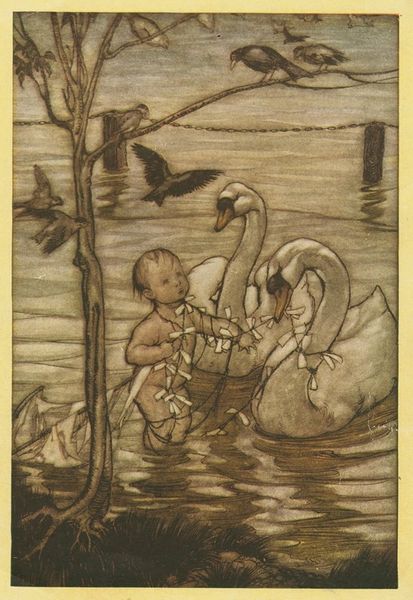

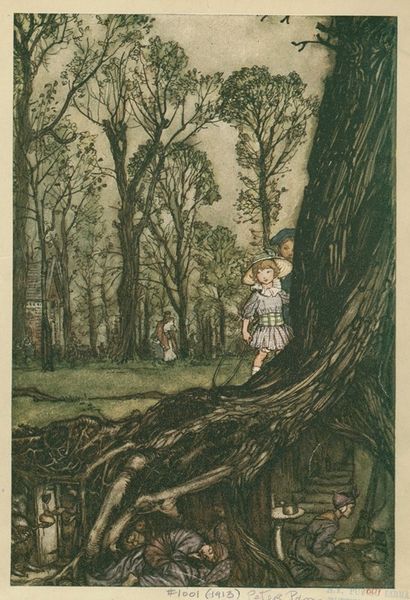

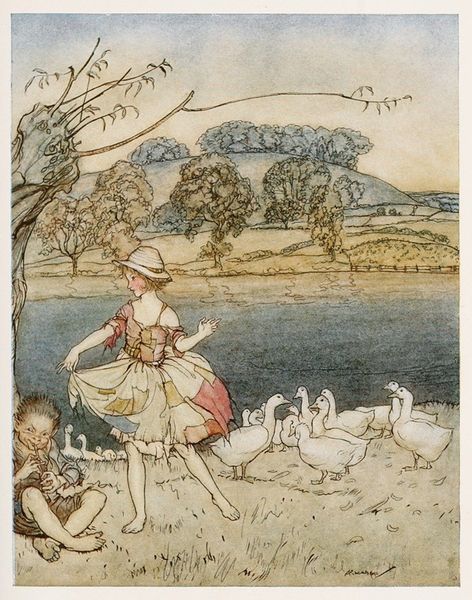

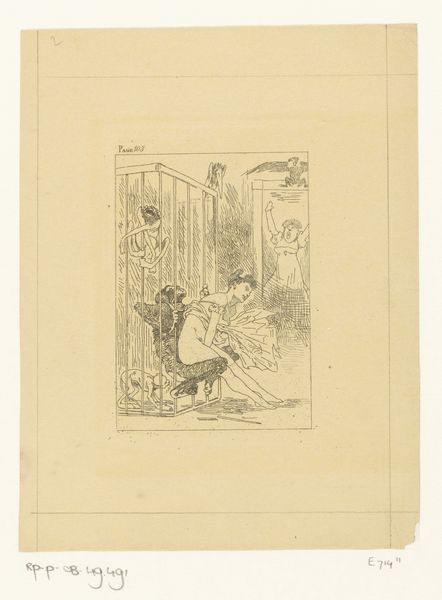

Curator: "In the Park," tentatively dated between 1915 and 1925, attributed to Eliza Draper Gardiner, presents a charming scene rendered through colored pencil drawing. The work, residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, immediately strikes a chord of gentle nostalgia. What's your initial read? Editor: My first thought is how much the image feels enclosed, the child hemmed in. It’s this tension between childhood innocence, evoked by the playful composition, and this sort of formal restraint through the tonality and shallow space that piques my interest. Curator: Precisely. And that tension manifests clearly within the making. Note the distinct graphic style, how Gardiner seemingly adopts the flatness of ukiyo-e prints combined with her drawing technique, blurring the distinction between "high" art and popular craft practices, likely influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and a fascination with global sources for the creative process. The production methods she used clearly echo mass reproduction and consumer access. Editor: Yes, the flatness immediately spoke to me. There’s an overt awareness of surface; the way the pigments interact reminds me of late 19th-century post-impressionistic exploration. I am compelled by Gardiner's compositional structure. She segments the pictorial space. The curve of the tree, the positioning of the figure, it directs the eye to weave and return. It almost suggests a stage set. Curator: Agreed, this is no straightforward landscape. Think of how it was encountered, reproduced and traded, consumed within an early 20th-century market shaped by mass culture. She also complicates the tradition of figuration by portraying a very modest individual, reflecting changing social class perceptions of everyday experiences and representations of labor and childhood. Editor: It begs the question, does this accessibility, the image's reliance on familiar compositional structure coupled with overt signs of manual labor, allow the work to transcend pure representation? Gardiner asks us to consider not just "what" is depicted but "how" it is visualized and circulated, thereby revealing meaning. Curator: I find it intriguing that this print also offers, simultaneously, a moment frozen in time and a testament to the historical currents that influenced its making. Editor: So true. Considering the form and context has allowed us to look more intently at how Gardiner achieves a very sophisticated balance between charm and subtle social commentary.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

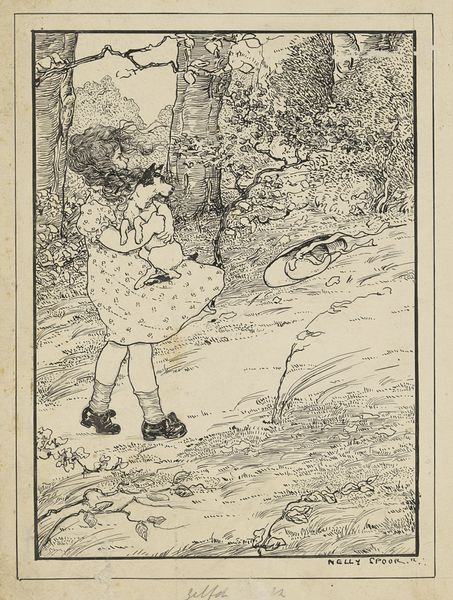

Eliza Draper Gardiner’s scenes of childhood combine sentimentality with strong composition. Here the arrangement is especially effective: the area circumscribed by the curved tree and curved bank echoes the form of a goose’s rear end. The subtle palette and painterly color—so characteristic of Gardiner’s work—suggest the innocence of childhood. Gardiner draws us into the scene through the boy’s total absorption in the bird’s movements. Let’s hope the boy has enough treats to satisfy the goose! A lifelong art teacher and lifelong Rhode Islander, Gardiner converted a barn into a studio on a small cove near Providence. After printing her woodcuts, she hung them on a clothesline to dry, just the kind of thing a child in one of her prints might have done.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.