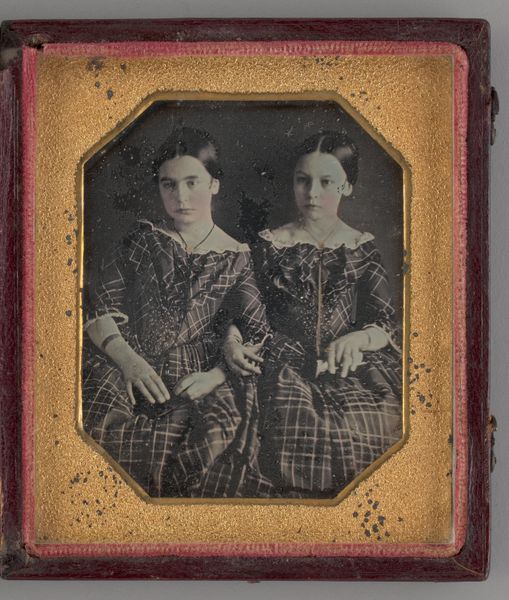

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

toned paper

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

child

#

geometric

#

united-states

Dimensions: 14 × 10.8 cm (plate); 15 × 12.1 × 1.5 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

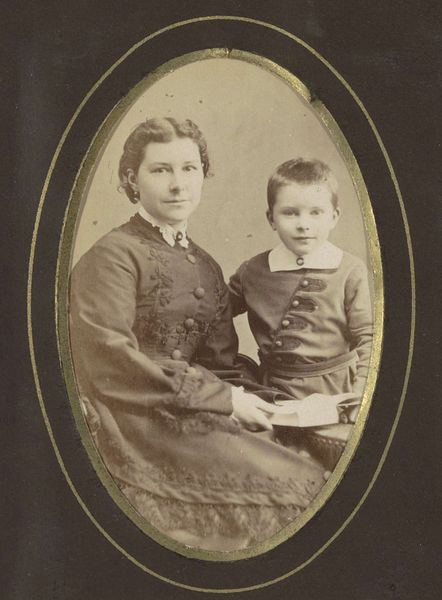

Curator: This daguerreotype, simply titled "Untitled," was created sometime between 1848 and 1856 by Charles H. Fontayne. Editor: It's remarkably stark. The image itself seems almost… hesitant, like a memory fading at the edges. I notice a lot of surface imperfections and spots which seem to heighten its ephemeral quality. Curator: That's a key element of the daguerreotype process, where the image is directly on a polished silvered copper plate. Notice the tight, almost geometric arrangement of the subjects—a woman and a young child—pressed into this oval frame. The tonal range, though limited, provides subtle gradations. Editor: And the lack of expression on their faces contributes to this overall sense of austerity. We might consider what it meant for women and children to participate in this technology. Perhaps these are deliberate gestures to establish social worth, gender, class, and other parameters through visibility in an increasingly public visual sphere? Curator: I see your point. Yet, also look closely at the relationship established through formal means. See how their hands, clasped in the very center, visually anchors them. The textures in their dresses create a pattern that spreads from one to the other as well. Editor: Right, these dark textiles can also suggest a family’s mourning in this era, a historical detail with far-reaching impact. Perhaps such material scarcity or emotional hardship might offer a powerful commentary on class. It causes me to question what "truths" can be conveyed or suppressed in this new medium. Curator: Yes, there's an undeniable tension between representation and interpretation. The daguerreotype itself serves as an artifact worthy of visual examination—while inviting broader socio-cultural understanding. Editor: Ultimately, it highlights photography's potent role in constructing narratives, and inviting audiences to question whose stories get told, and how. Curator: Indeed, prompting me to reassess what seems still—and what, with further study, shifts right before your eyes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.