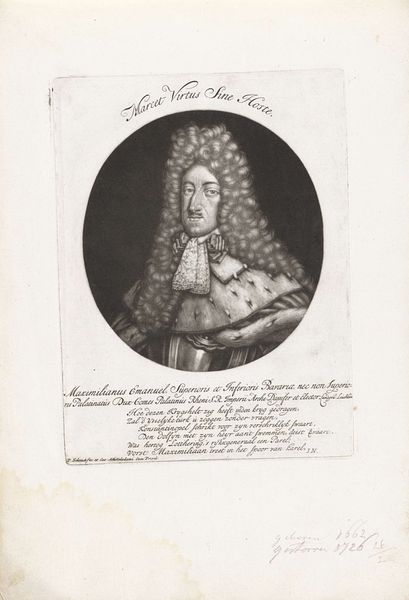

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, here we have Pieter Schenk’s engraving depicting Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy. The work, housed at the Rijksmuseum, is dated somewhere between 1680 and 1713. Editor: First glance? Oof, a lot of wig. And the expression… utterly unimpressed. Like he just stubbed his toe but remembered he’s a Duke, so he can’t show it. Curator: That "wig," as you call it, isn’t merely an accessory; it’s a deliberate assertion of power and status, deeply entangled with Baroque fashion. It mirrors, in many ways, the performativity of aristocracy itself during that period. The armor he's wearing underneath—do you see the intricate details? Notice the fleur-de-lis patterns worked into the metal. It’s less about battlefield utility and more about signaling allegiance. Editor: It's definitely fancy! Like battle bling. Still, even with all the symbolic flourishes, he looks rather...doughy. Is that too mean? Curator: It’s… an observation. But perhaps we can explore how these very human, perhaps unflattering, representations destabilized or even subtly challenged the conventions of heroic portraiture. Remember, prints like this circulated widely. They were a form of political communication, disseminating images of rulers but also opening them up to public scrutiny and interpretation. Think of it as a pre-Instagram era of image crafting. Editor: A Duke selfie! Right. Except, back then, filters were really expensive and made of metal. Did folks actually see past the...image and consider the power dynamics at play? Or were they just admiring the lace? Curator: The two aren’t mutually exclusive. The consumption of art always exists at the intersection of aesthetics, power, and social context. Think about who was *able* to access these images, and what those images communicated to different social groups. These prints helped forge a collective identity but also, potentially, spurred dissenting views or even resistance. The circulating images were an act of solidifying power, even while the printing itself allowed more access to potentially dissenting or destabilizing dialogues. Editor: Hmm. I guess the Duke's face—stubbed toe and all—is just the beginning of a much bigger, hairier story. I suppose it invites me to go beyond just the appearance, to see the whole sociopolitical theatre at play in just this one little print. Curator: Precisely. The ripples extending far beyond that stoic expression—or impressive wig.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.