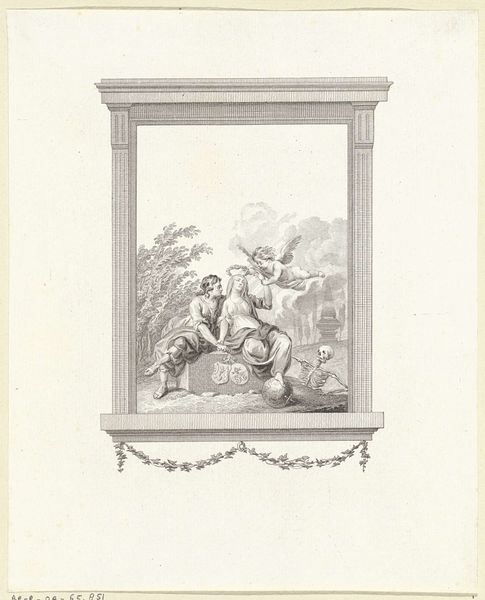

Dimensions: height 238 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving by Reinier Vinkeles, titled "Paar herenigd na de dood" – "Couple reunited after death" – and dating from 1751 to 1816, one is immediately struck by the sentimentality, wouldn't you say? Editor: It certainly evokes strong emotions. I'm immediately drawn to the lines, though—the clear marks, the delicate hatching that builds form out of apparent nothingness. It speaks volumes about the engraver’s skill, forcing a tactile experience onto an ethereal subject. Curator: Absolutely, the technical mastery is undeniable, but I think the allegory is so evocative. The female figure, presumably the deceased, reaching out to welcome her partner, framed by light and angels. There’s a powerful suggestion of redemption and eternal love. It clearly speaks to shared beliefs about love transcending death. Editor: While the theme of reunion is interesting, I am more fascinated by the production of this work, the labour involved. Vinkeles was using a very particular set of tools, engaging in what some might dismiss as mere reproductive craft to communicate these symbolic languages to a wide audience. Who were the intended consumers of such an image, and how does this object articulate certain values that people cherished? Curator: That’s a vital point. Engravings like these circulated widely and democratized access to powerful emotional narratives. Think of the visual language it employs. The laurel wreaths are symbolic of eternal life. And this embrace transcends earthly grief, hinting at a romantic idealism characteristic of its era. We must remember the audience's familiarity with these images for comfort. Editor: And yet, consider how the materials themselves mediate that comfort. This wasn't a unique, precious object destined for a wealthy patron’s private collection, but a printed image available to the middle classes. How does this material reality alter the consumption of grief and the ideals surrounding love after death? What other meanings do viewers, embedded within particular economic structures, bring? Curator: Indeed, its replicability affects how it was experienced, serving to promote not only hope but cultural cohesion in grief. In essence, it offers a vision of idealized afterlife to people who faced significant worldly struggles. Editor: Thinking about the print in its socio-economic setting offers so many pathways to understanding it. The image, and the engraving processes involved, acted as both a carrier for shared meanings and values for disparate individuals in eighteenth-century Dutch society. Curator: I agree. Considering the engraving as a cultural artifact rather than a solely aesthetic one deepens our appreciation and sheds light on shared cultural meanings and values. Editor: Absolutely. Exploring this work really made me question the supposed division between so-called ‘fine art’ and these modes of wider production and consider the various forms of labour involved in meaning-making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.