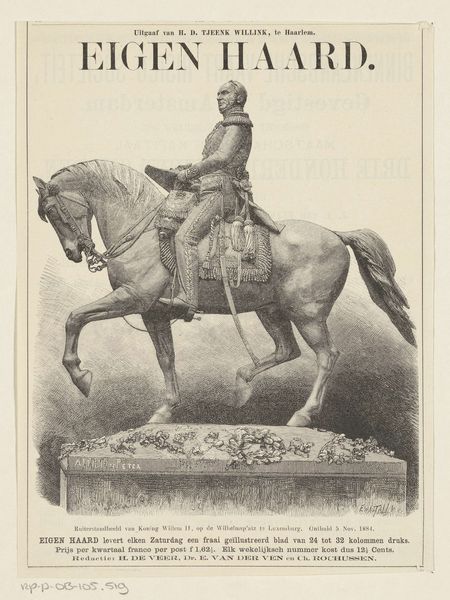

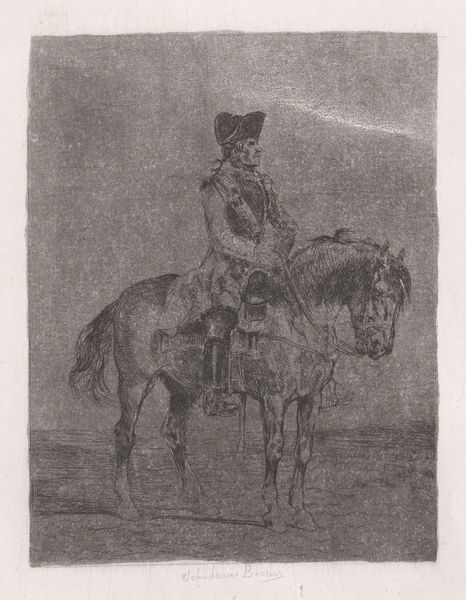

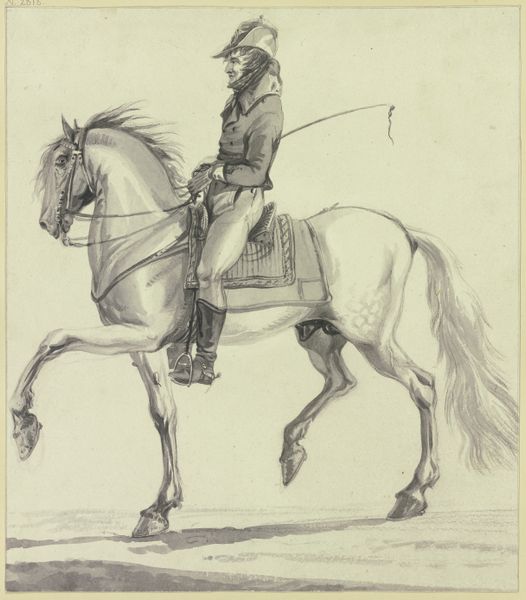

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Right, let’s take a look at this engraving, “Portret van FitzRoy Somerset” or "Portrait of FitzRoy Somerset," which dates between 1846 and 1876. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum, and was created by Carel Christiaan Antony Last. What strikes you most about it? Editor: There's a formality, almost a stiffness to it. A sort of heroic posturing that I'm not sure resonates as deeply now as perhaps it once did. The man and his horse seem disconnected; a curious blend of grandeur and… awkwardness, perhaps? Curator: It's interesting that you find it awkward! Remember, equestrian portraits were often about displaying power and authority. This portrays FitzRoy Somerset, also known as Lord Raglan, who was a prominent British Army officer. His distinguished bearing on horseback was deliberately designed to convey a certain image. Editor: Oh, I get that, intellectually! But, emotionally? I look at the rendering of his uniform—precise, yes—but somehow lifeless. It lacks the vibrancy that truly communicates character. And the horse… magnificent animal, but also rendered a bit mechanically. The emotional current feels suppressed. Curator: That suppression, as you call it, speaks volumes about the conventions of portraiture at the time. This isn't meant to be an intimate study. It’s designed to reinforce social and military hierarchy. This work served as propaganda intended to be widely disseminated through prints. How do you read this "mechanically rendered" style in connection to propaganda? Editor: Propaganda... hmm... That's what troubles me. Doesn't this remove the art from its social consequences by cloaking it in superficial finery? We celebrate supposed triumphs, and risk blinding ourselves to other, untold stories. Curator: But, it's crucial to consider its impact on the public, too. Think of the proliferation of images like these at the time. It cemented the hero status, and the idea of imperial authority and power was then visualized and reproduced. Editor: Absolutely, it is interesting as a socio-political object. I might admire it on some purely technical level, yet still question its celebration. We need, rather, to cultivate critical engagement and reflection about what exactly those symbols represented—and still might represent—in culture. Curator: Well, seeing how an image like this impacts your critical sense definitely adds a new perspective. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.