photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

photography

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 120 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

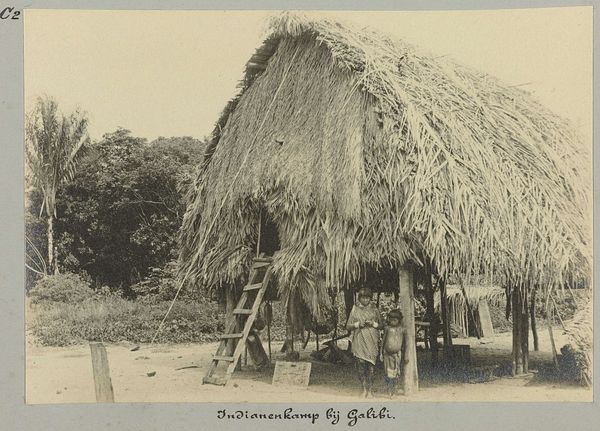

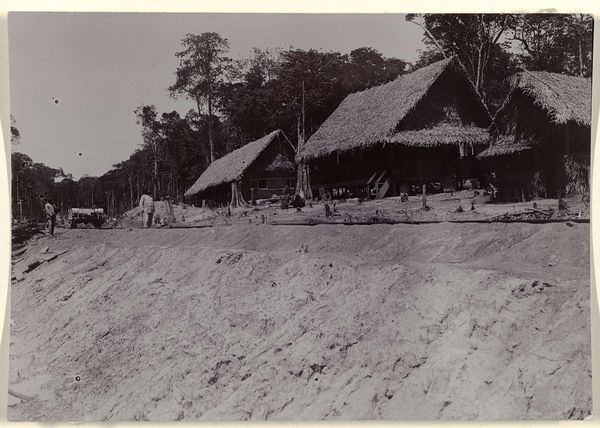

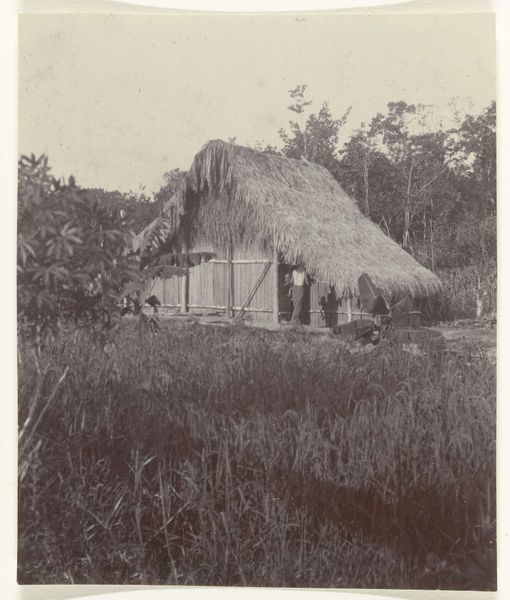

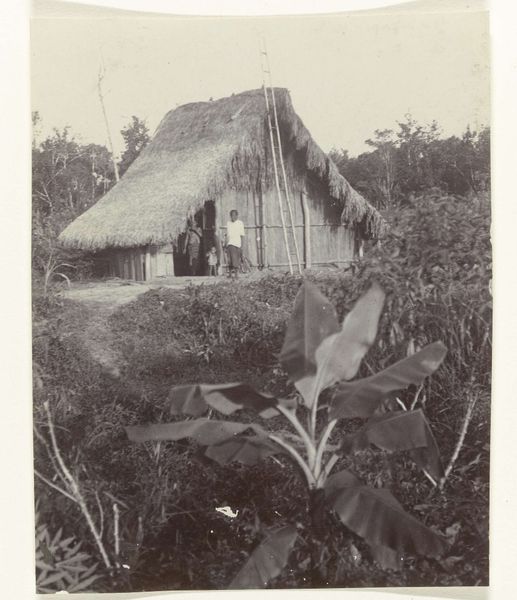

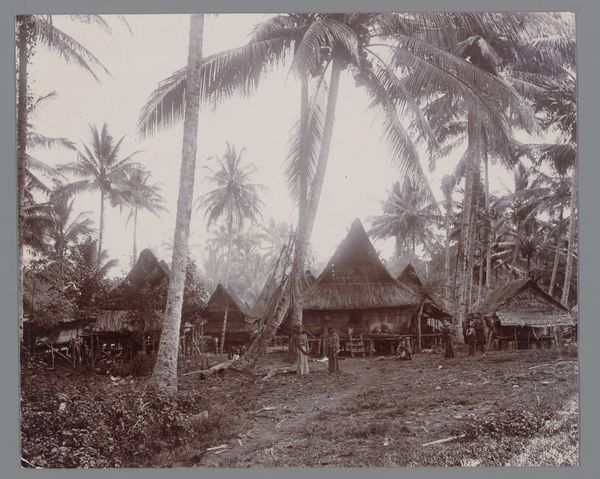

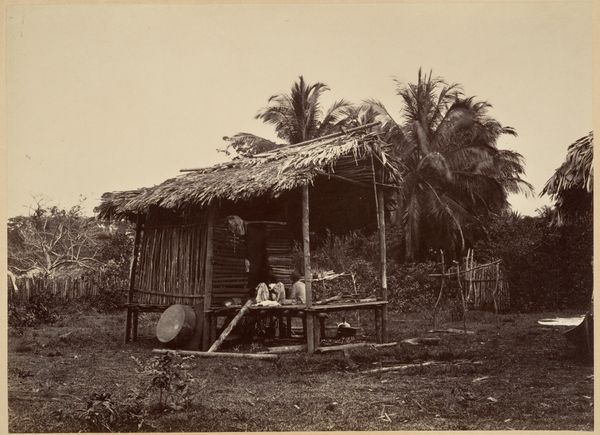

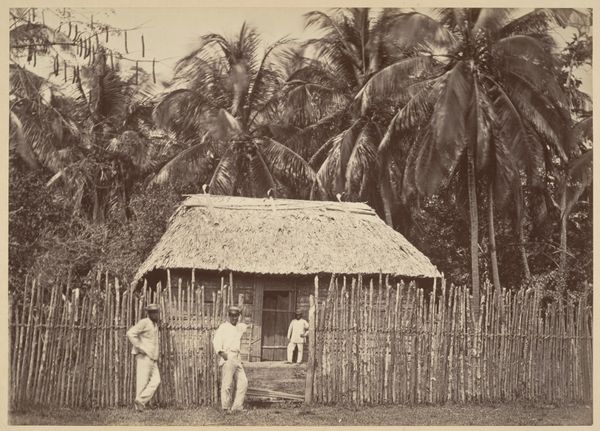

Editor: Here we have Hendrik Doijer's photograph, "Caraïbendorp bij Galibi, Suriname," taken sometime between 1903 and 1910. It captures three thatched structures that seem so vulnerable. How should we approach reading an image like this? Curator: The photograph is not merely a landscape; it’s a document embedded in colonial history. Consider the act of photographing. Who is doing the looking, and for what purpose? These images were often used to portray indigenous life in ways that served colonial agendas, marking territories and "documenting" cultures deemed in need of civilizing. Editor: So, the camera becomes a tool of power? Curator: Exactly. Photography like this shaped European perceptions of the ‘Other.’ Notice the distance the photographer keeps. There is a clinical detachment that frames the Carib village as an exhibit, an example. The lack of people, it’s staged somehow, absent of the activity, or dynamism, of people living there. Do you see the composition reinforces a narrative of the exotic and primitive? Editor: I see that now. So instead of viewing this photograph as a straightforward representation, we need to examine it critically as a product of a specific historical and political context. What looks like simple documentation is loaded with cultural bias. Curator: Precisely. And that bias had very real consequences in how these communities were treated and understood by the outside world. Think about what’s *not* being shown, what’s been excluded, and whose voice is absent. Editor: It’s really made me think about how images, even ones that seem neutral, can carry so much historical weight. Curator: Absolutely. Now, you might ask, how can a contemporary viewer counteract some of this past damage with careful consideration?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.