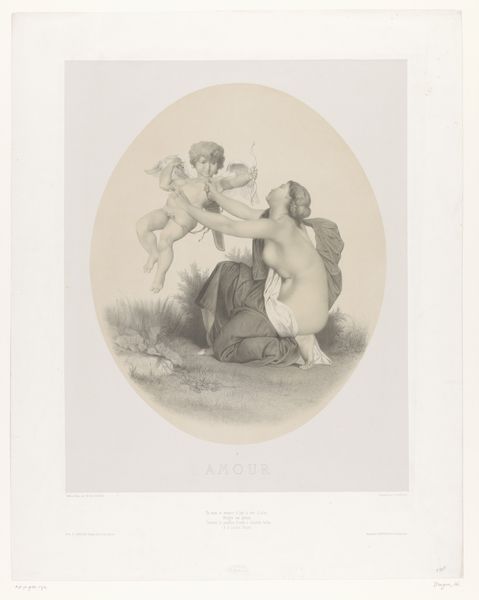

Dimensions: height 694 mm, width 549 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

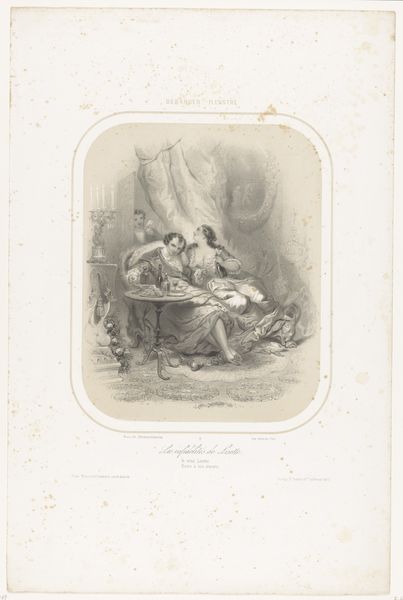

Curator: This delicate pencil drawing, made between 1855 and 1856, is entitled "Venus voelt aan de pijlpunt van Cupido," or "Venus Feeling Cupid's Arrowhead" by Charles Bargue. It’s quite a sentimental scene. Editor: The textures, particularly in Venus' drapery, strike me first. You can practically feel the weave of the cloth through the varying pressure of the pencil. Curator: Precisely! The almost photorealistic shading that renders both Venus and Cupid showcases the influence of Academic Art during this time. There's also an undeniably romantic and idealized approach to representing these mythological figures. We must acknowledge the cultural context in which the male gaze dictated portrayals of women, particularly goddesses. Editor: That link between industrial-era techniques of image reproduction and the continued depiction of idealized, timeless bodies is interesting. What kind of pencil do you think Bargue employed to achieve such gradients? How was pencil manufacturing developing? Curator: We know that Bargue created it as a lithographic model. I'd also like to discuss the implicit power dynamics between Venus and Cupid, here portrayed not just as mother and child but also within the broader sociopolitical context of idealized femininity versus mischievous male authority. It brings questions of agency and control into sharp relief. Editor: Power definitely exists within the gaze represented here. However, this makes me think about the socio-economic position of lithography at that moment in history. Reproducibility opened channels of accessibility to those who might not be able to afford an original piece of artwork. How were the illustrations distributed and who bought them? Curator: Those economic dimensions are really important for us to remember! In reassessing this artwork today, we recognize these factors but simultaneously allow space for more modern feminist interpretations that acknowledge these complex layers within depictions of femininity. Editor: It's a compelling reminder that art history is always a conversation, an exchange between the object, its maker, its multiple audiences. Thank you for your thoughts. Curator: Yes, it is a continuous cycle of contextualisation and recontextualisation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.