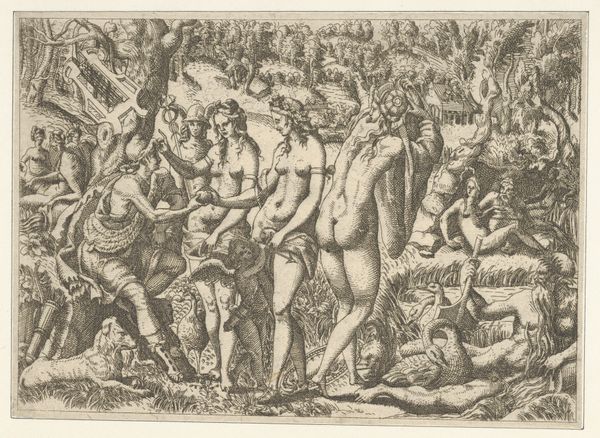

Naakte man met fakkel staat op sokkel omringd door naakte mannen met paard en vaas en soldaat geflankeerd door deugden Voorzichtigheid en Liefde 1510 - 1527

0:00

0:00

marcantonioraimondi

Rijksmuseum

drawing, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 270 mm, width 374 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have “Naakte man met fakkel staat op sokkel omringd door naakte mannen met paard en vaas en soldaat geflankeerd door deugden Voorzichtigheid en Liefde,” a pen drawing in ink by Marcantonio Raimondi, made sometime between 1510 and 1527. There is an intensity here—a celebration of the nude form in a very active landscape. How do you see this work fitting into the visual culture of its time? Curator: This engraving presents a fascinating case study in the dissemination of classical ideals during the Italian Renaissance. Raimondi, a key figure in printmaking, played a vital role in circulating artistic ideas. Notice how the composition draws heavily on classical sculpture and mythology. It’s not just a drawing; it’s a political statement about cultural aspirations. Editor: So, the deliberate referencing of classical imagery served a specific purpose beyond aesthetics? Curator: Exactly. The rediscovery of classical texts and art fueled a desire to emulate the perceived grandeur of antiquity. Printmaking allowed for the mass production and distribution of these images, thereby promoting a shared visual language among artists and patrons across Europe. Think about the Medici family's patronage and their investment in classical scholarship—how might a piece like this play into that socio-political environment? Editor: It's like the artwork itself becomes a form of cultural currency. By owning or circulating such an image, patrons associated themselves with the power and prestige of the classical world. I’m struck by how calculated this image feels, not just in its composition, but in its purpose. Curator: Precisely. Understanding the cultural context allows us to see the artwork as an active participant in the shaping of Renaissance identity. Editor: I never would have looked at this as a piece that is consciously involved in its political ecosystem. Curator: And that, perhaps, is the most important takeaway. Art never exists in a vacuum.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.