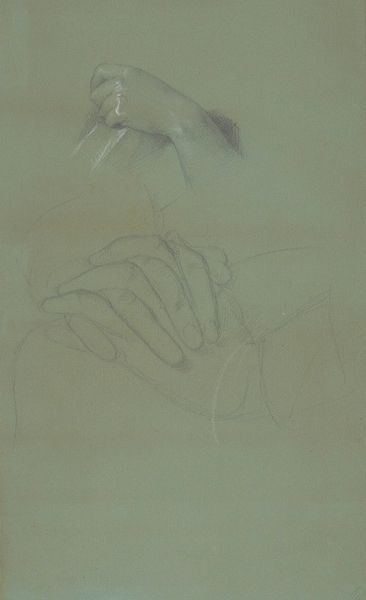

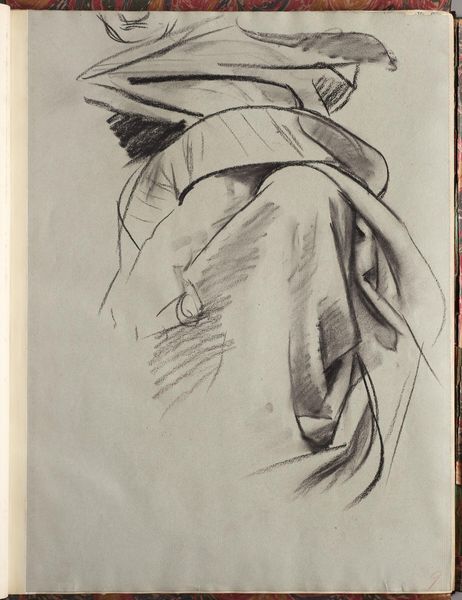

drawing, charcoal

#

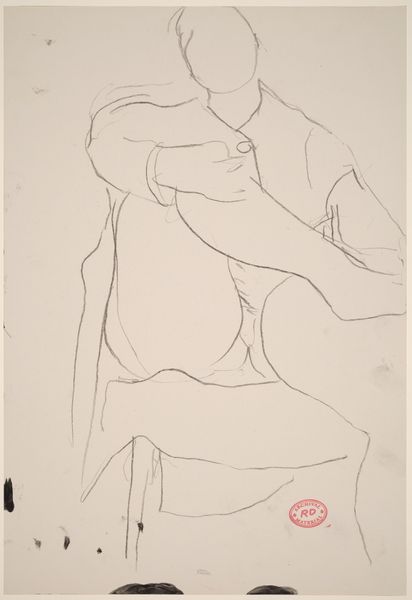

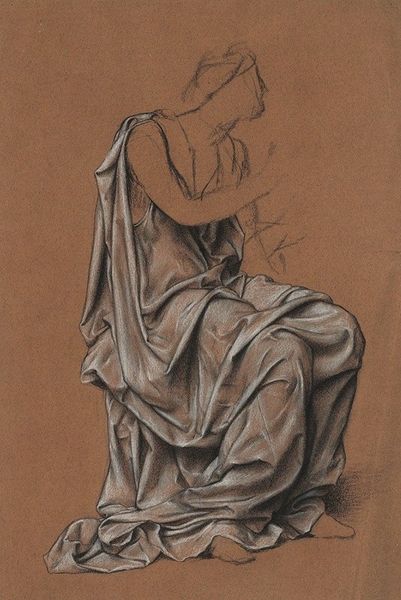

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

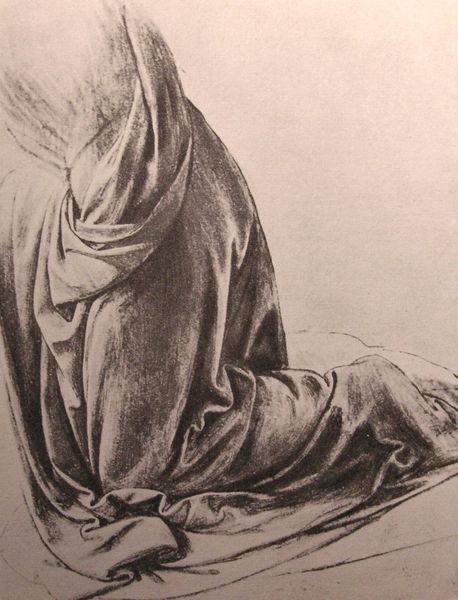

drawing

#

cubism

#

charcoal drawing

#

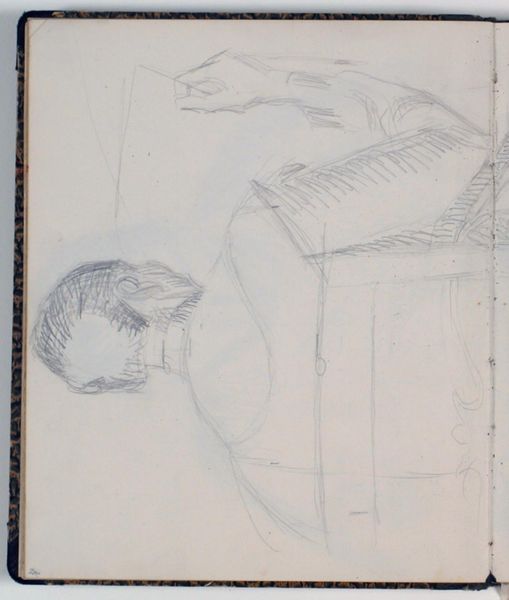

pencil drawing

#

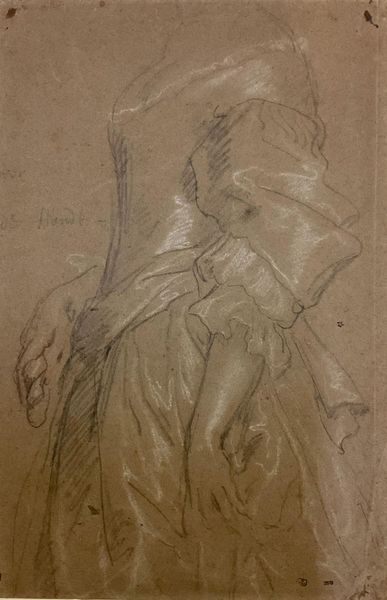

charcoal

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before María Blanchard's "Campesina," or "Peasant Woman," rendered in 1922. It’s a striking charcoal and pencil drawing, demonstrating Blanchard’s move into Cubism. Editor: The first impression I get is a sense of somber introspection, but the fracturing effect of Cubism is more muted, which I find interesting. There's a tenderness in the sitter’s downward gaze. Curator: Absolutely. Look at how Blanchard, as a woman artist working within a male-dominated Cubist movement, uses that geometric vocabulary not to dissect or fragment the figure into purely abstract form, but to explore a sense of interiority and lived experience. It complicates readings around representation of women. Editor: The hands are quite large and angular, a powerful image with years of toiling under harsh conditions suggested by it. They have this strong, almost block-like quality and could relate to older symbolism regarding the role and character of female peasantry. The Cubist treatment almost acts as a form of idealization, representing something essential, almost eternal, about the figure. Curator: I agree; they speak to labor, to a historical understanding of the female figure's role in the field. Given the socio-political upheavals across Europe at that time, this imagery connects to broader themes around class consciousness and gender roles, while perhaps representing her own experiences. Editor: I’m struck, too, by the almost childlike rendering of the face; and though somewhat abstract, her facial features show an innocence, but one clearly worn by hardship and perseverance. I'm thinking about other mother-and-child iconographies through history. Curator: The peasant figure, for Blanchard, serves as an embodiment of resilience, especially given the social realities of early 20th century Spain. Blanchard situates the campesina within a network of power relations and identity politics, representing women not as symbols of beauty but rather, in ways that reflect a profound sense of humanity. Editor: And it encourages us to contemplate the legacy of those symbols as they intersect with art historical precedent. A compelling depiction overall. Curator: Indeed. It is through her charcoal marks that we connect, in time and space, with a social reality that perhaps we too should come to appreciate.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.