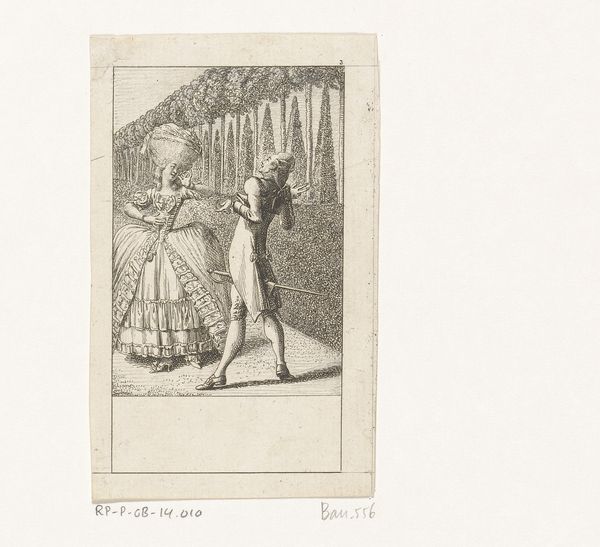

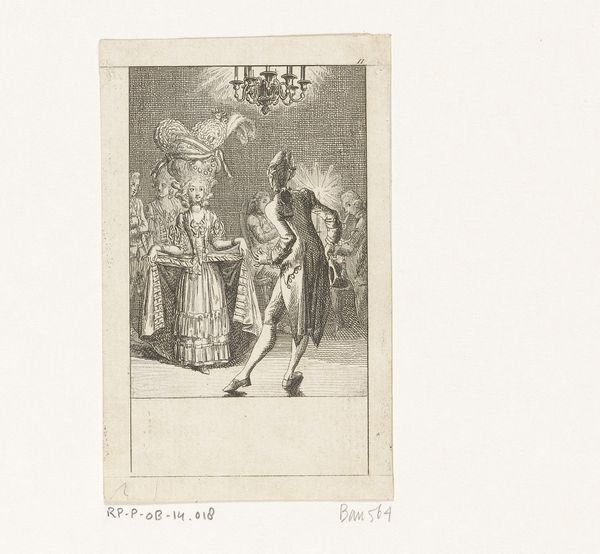

Ontwerp voor In Holland staat een Huis: silhouetten van een man knielend voor een vrouw 1884 - 1917

0:00

0:00

nellybodenheim

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 75 mm, width 92 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Nelly Bodenheim's "Ontwerp voor In Holland staat een Huis: silhouetten van een man knielend voor een vrouw," created sometime between 1884 and 1917. Editor: Striking! There's an immediate visual tension. The stark silhouettes against the pale background create such a dramatic and, dare I say, romantic narrative. Curator: Bodenheim, though often associated with children's illustrations, engages here with potent visual tools and thematic interests from the period. The medium itself, ink on paper, signals its connection to printmaking, crucial for disseminating imagery within a culture and indicative of certain audiences. The image directly translates to 'Design for In Holland stands a house: silhouettes of a man kneeling for a woman'. Editor: Exactly. That inherent contrast – the darkness defining form – really draws the eye. Look at the composition! The man's kneeling pose juxtaposed with the woman's upright posture; a very formal and considered structural layout implying conventional gender dynamics. Curator: The materiality speaks to accessibility. Ink and paper were readily available, enabling broad engagement with visual culture and even home-based crafting. Considering this silhouette style was quite popular in the 19th century, and could be cut and replicated en masse, this shifts our understanding to the artistic labour involved as not inherently tied to singular creation or ‘genius’, but to a social craft and reproducible artwork. Editor: Perhaps! However, the meticulous detailing—look at the man’s ornate attire and the woman's elaborate headpiece—also points toward an aristocratic or upper-class social stratum. The attention to the clothing creates very definite cues. Curator: But how do these visual symbols operate within the broader market forces affecting artists at the time? And furthermore, can we examine how the materials would be consumed, adapted, and read within a social context that is itself defined by unequal power dynamics and gender roles? Editor: Regardless of those production specifics, I return to that visual tension – the intimate act conveyed through a detached, almost theatrical, representation. The precision of line, the balance of light and shadow. These are formal elements working powerfully. Curator: Precisely. The confluence of available resources and design gives insight into how Bodenheim adapted visual methods, and was possibly reproduced in publications or artistic collections, revealing networks of artistic labor. Editor: In either case, thinking through line, composition, and historical technique provides much to reflect upon. Curator: Indeed. From material conditions to visual dynamics, it opens our appreciation to Bodenheim’s work and place in art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.