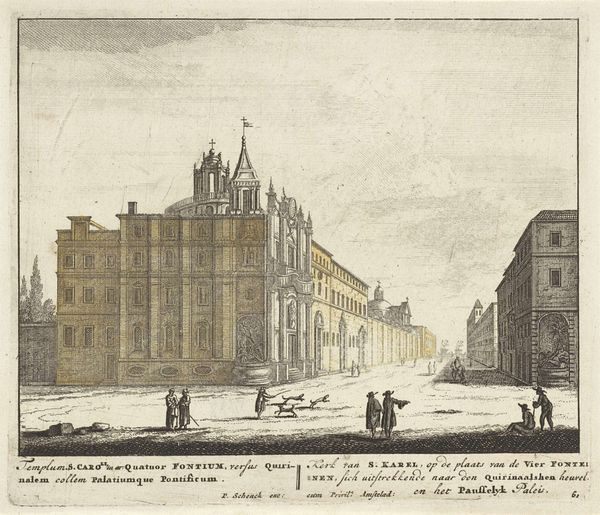

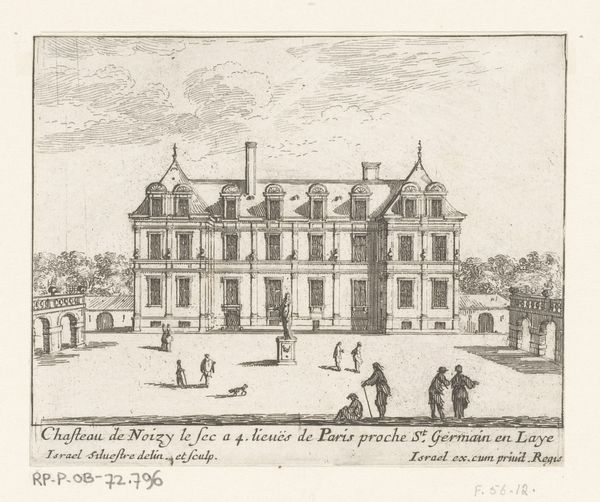

drawing, etching, ink, pen, architecture

#

pen and ink

#

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen illustration

#

etching

#

ink

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

architecture

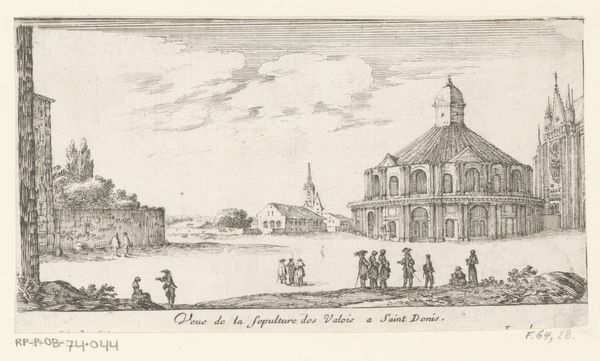

Dimensions: height 87 mm, width 109 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Israel Silvestre's "Gezicht op de Église de l'Annonciation," dating roughly from 1631 to 1661, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s rendered with pen, ink, and etching techniques. Editor: The level of detail is extraordinary. There is an understated drama in its quietude that almost vibrates against the sharp linework of pen and ink. What immediately catches my eye are the social dynamics that can be read out of the material relationships between people and architecture here. Curator: Precisely! Silvestre was renowned for his cityscapes. Consider how the building’s placement dominates the public space. Silvestre creates an idealized scene. These images weren’t simply records; they bolstered a specific view of Paris as a seat of power. Editor: This resonates strongly. Note the activity around the square, yet the architecture looms. It projects authority, doesn't it? Consider the perspective itself – from slightly below, reinforcing the church's imposing stature. It implicitly promotes acceptance of the church and of religion's position, regardless of class. Curator: Very astute. Also consider who gets memorialized by this kind of imagery: civic elites. Their patronage, both ecclesiastic and political, solidified and funded the creation of architectural works and images of them, too. In effect, those figures determined which physical and representational structures deserved continued cultural importance. Editor: So this print functions as an endorsement. As we know, throughout much of art history, art making was a privilege. Representation—who is represented, how, and why—became an act with sociopolitical impact and implication, and an important element in discussions around agency. Even if unintentional, that viewpoint and emphasis shapes collective perceptions, beliefs, and systems of power that linger. Curator: Exactly. The composition uses the rigid facade to express institutional values, yet notice how daily life skirts its edges in an era defined by monarchical divine right. Art shaped and solidified those concepts. Editor: It certainly offers a glimpse into how urban life was rigidly shaped. The architecture feels like an imposing entity, one that still prompts questions today about the interplay between faith, power, and people. Curator: I agree; art never truly lets go of the era that created it, making historical art viewing an intersectional enterprise. Editor: Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.