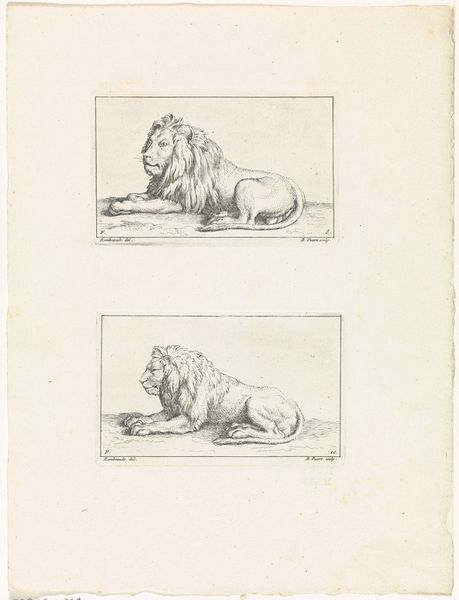

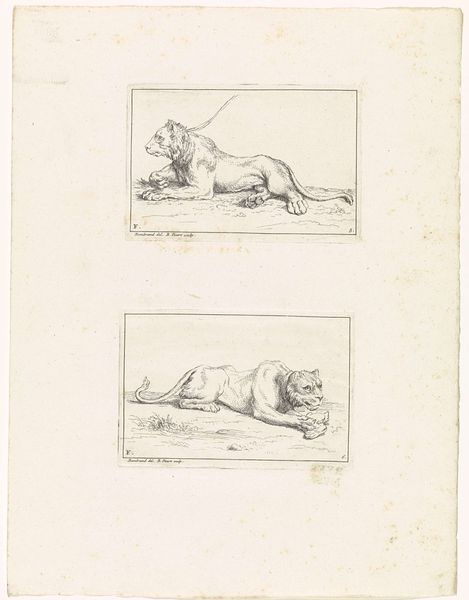

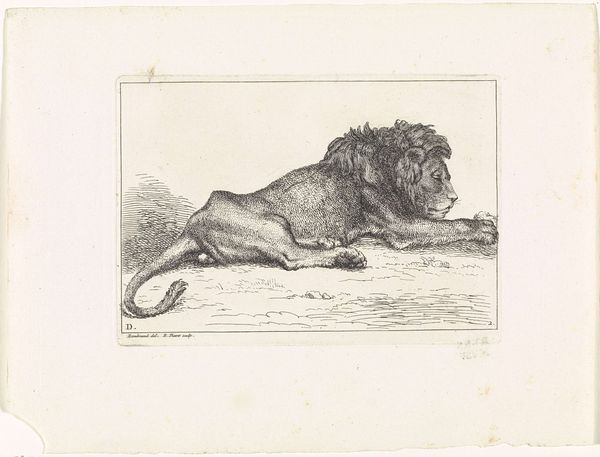

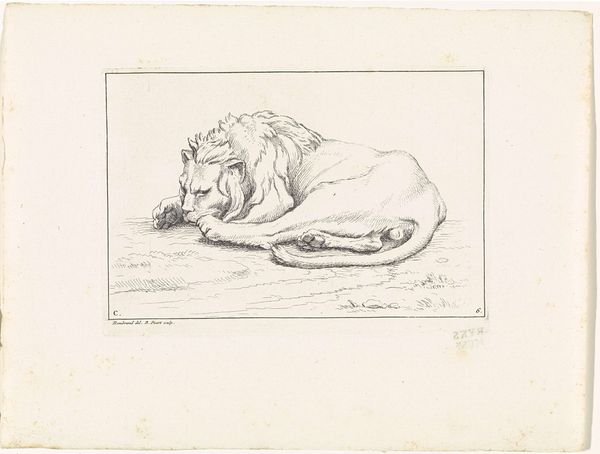

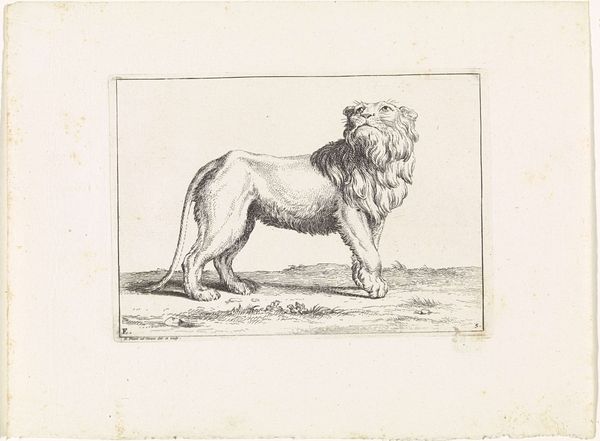

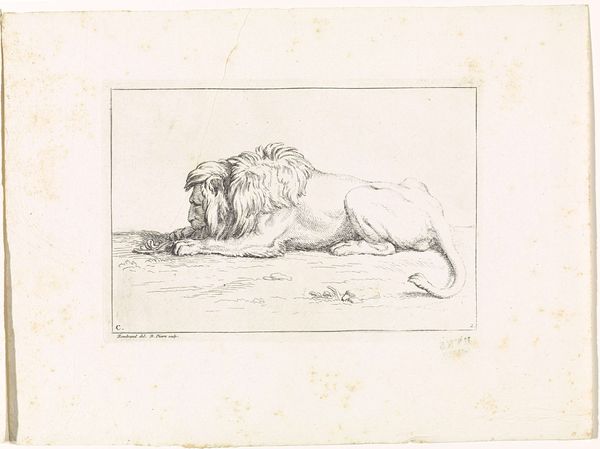

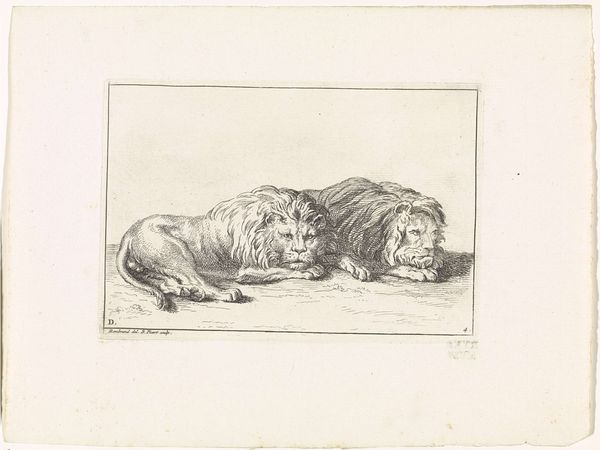

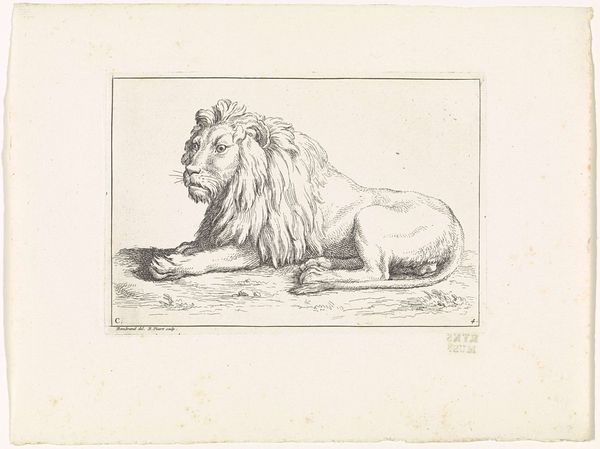

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

quirky sketch

#

animal

# print

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

realism

#

initial sketch

Dimensions: height 70 mm, width 114 mm, height 70 mm, width 113 mm, height 269 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So this is "Leeuwen" by Bernard Picart, created in 1728. It’s an engraving. They look like quick sketches from a sketchbook... I'm curious about their raw and immediate feel. What jumps out at you about this print? Curator: Well, first off, I think we should examine this "print" more closely. The print medium democratizes image-making. Here we see the work of both Rembrandt and Picart. The inscription on the upper sketch indicates the original sketch was done after life. This raises important questions. What does it mean to make copies after life? How does the production and consumption of such imagery impact the relationship between humans and animals? Editor: That’s interesting! I was just seeing them as… drawings of lions. Curator: But they’re more than just that, aren’t they? Consider the labor involved in producing prints in the 18th century. The engraver meticulously carves lines into a metal plate, transforming a drawing into a reproducible image. What labor went into capturing the "likeness" of these animals? Where would these lions have been located at the time the image was made? Editor: So it's not just about the lions themselves, but about the whole industry around creating and sharing images of them. And how people's ideas about them are shaped by that. Curator: Precisely. How might this print have circulated, and what purpose did it serve? Was it intended for scientific study, artistic inspiration, or popular entertainment? The materiality of the print—the paper, ink, and engraving—becomes a crucial site for understanding its cultural work. Editor: I hadn’t considered it that way. Looking at the means of production and its consumption opens up new ways of thinking about a relatively simple drawing. Curator: Absolutely! The image becomes an object embedded in networks of labor, exchange, and meaning. And by analyzing these material aspects, we can challenge the traditional hierarchy that elevates artistic “genius” over the skilled work of artisans and the social contexts that shape artistic production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.