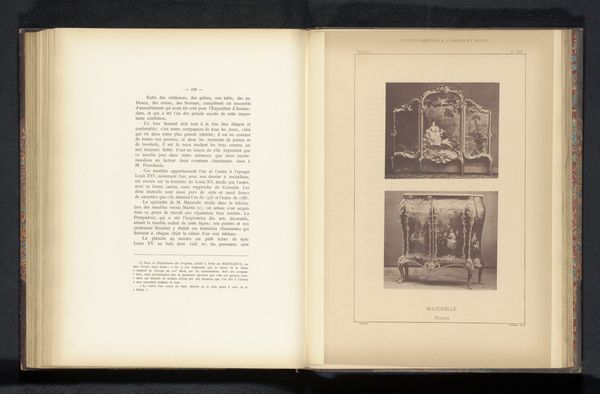

print, photography, engraving

#

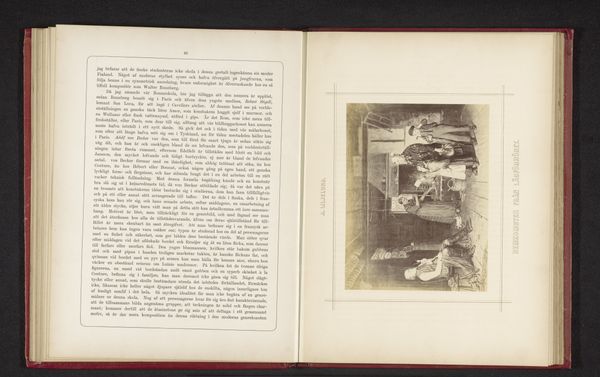

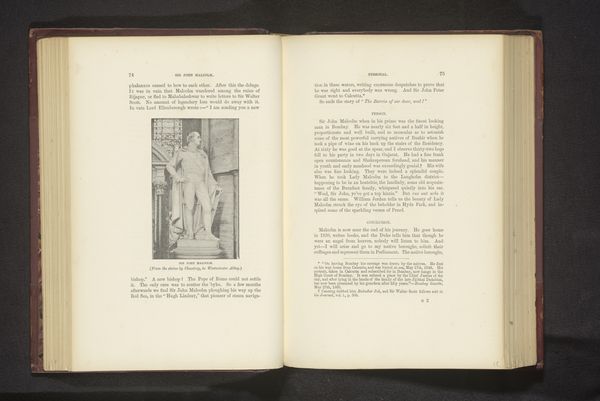

portrait

# print

#

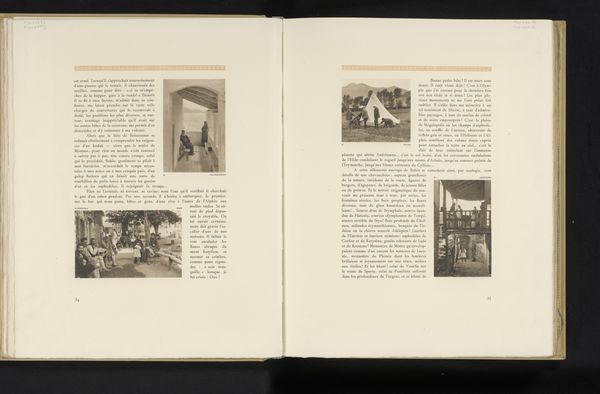

text

#

photography

#

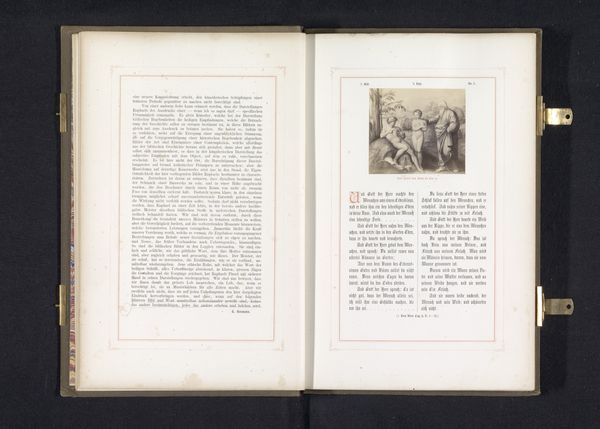

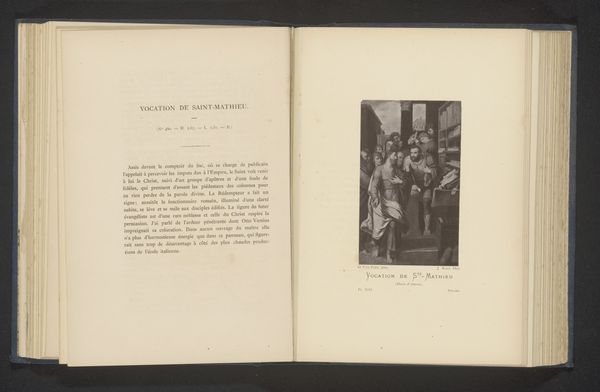

engraving

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a page from an antique book, featuring four portraits collectively titled "Vier portretten," dating to before 1893. It's a composite piece, incorporating photography and engraving in its production. Editor: The first impression I get is how…formal everything looks. The composition is static, almost clinical. And seeing them presented this way, embedded within the book itself, speaks volumes about their role within a larger historical and social fabric. Curator: Precisely. The placement of these images within the book is as critical as the individual portraits themselves. Who were these individuals, how were they positioned in society at that time, and how does the interplay between photographic representation and engraved reproduction impact how we perceive them? Editor: Consider, too, the means of production. Photography was rapidly evolving at this point, but incorporating it into a printed format like this would require skill and particular labour. There are inherent tensions here—between mass production and artistic intention, between scientific representation and social symbolism. Curator: Yes, the photographs themselves act as a documentary snapshot of a specific societal strata, the upper class during a time of significant shifts. Each sitter’s pose, clothing, and expression reflect an era defined by the rise of bourgeois ideals. Editor: It raises questions about authenticity too. Are we viewing the 'real' person or simply the curated presentation, a reflection of the aspirational values imposed on them? And what did it take, physically and socially, to create these lasting documents of self and identity? Curator: I think framing this work within a historical dialogue regarding visibility is vital. Whose stories are represented, whose aren’t, and who controls these visual representations? What are the ethical responsibilities involved? Editor: Right. It reminds us that these historical prints are artifacts themselves. They possess embedded stories not just about the individuals depicted, but about the labor, technology and industrial processes needed to construct the work. That means and mode of production is really key. Curator: Absolutely. Understanding the historical context, especially related to power dynamics in regards to access to representation, challenges any inherent assumptions we bring to the act of seeing. Editor: Indeed, examining “Vier portretten” using our frameworks—material and social—can highlight important ideas about labour, and what’s involved in forming our collective understanding of a particular moment in time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.