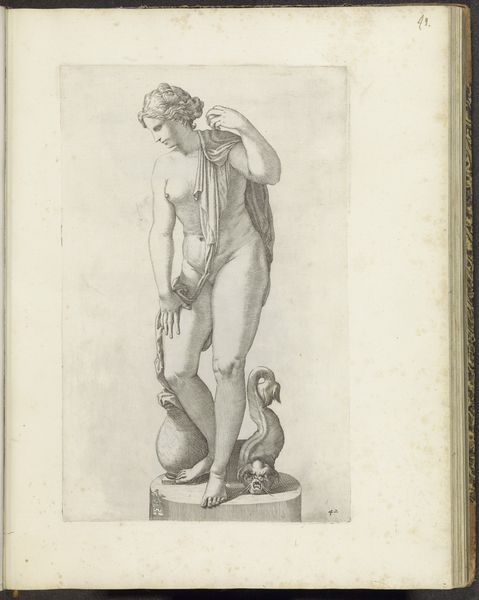

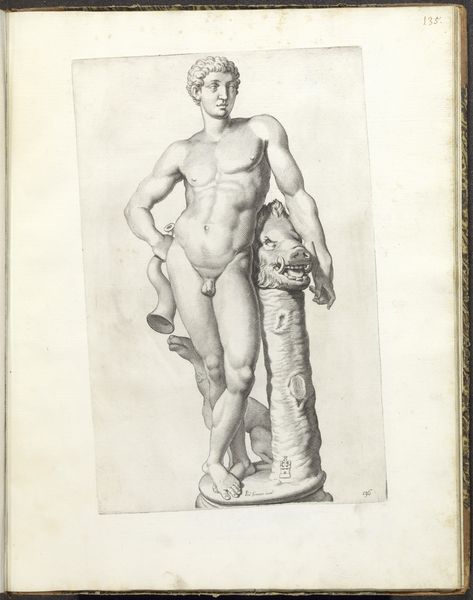

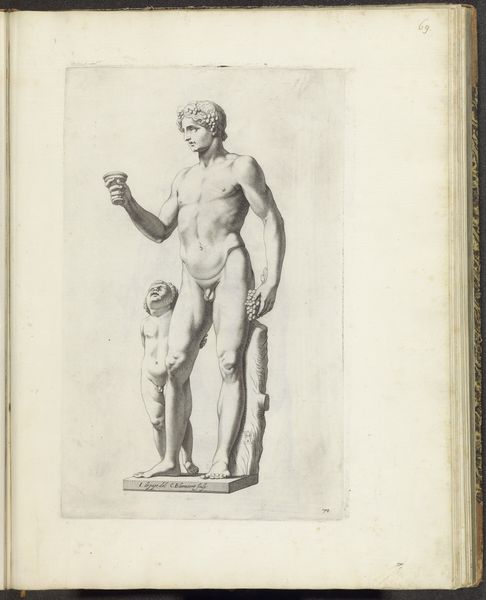

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

nude

Dimensions: height 370 mm, width 235 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

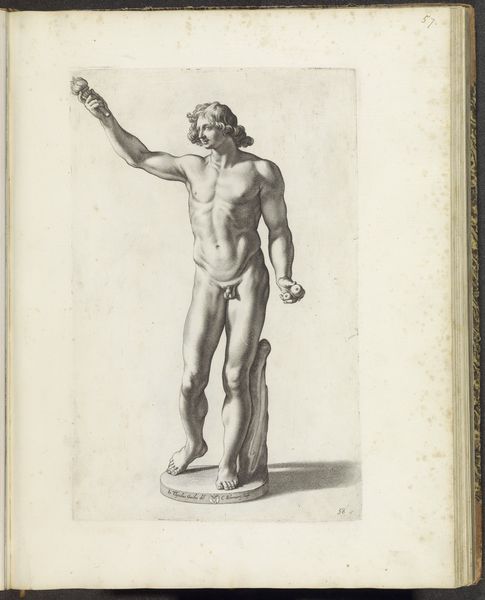

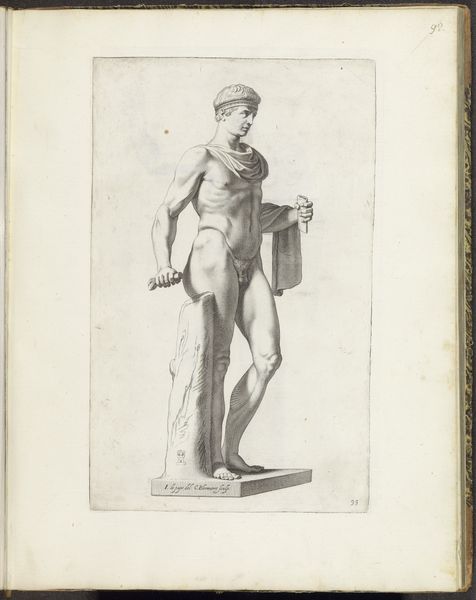

Editor: This is Cornelis Bloemaert's "Statue of Venus with fruit in her hands," dating back to sometime between 1636 and 1647. It's a drawing made with ink on paper. It’s interesting that we view Venus from the back, emphasizing the statue's form over the goddess’s face. What historical narratives or cultural values do you think this image reveals? Curator: This drawing offers a window into the art world's engagement with classical antiquity during the Baroque period. Consider the institutional framework: artists studied classical sculptures not only for their aesthetic value but also as models of ideal form, endorsed and propagated by academies. The depiction of Venus’s back instead of her face might signify a shift in emphasis towards the formal qualities of sculpture and a conscious attempt to demonstrate artistic skill through rendering anatomy. How do you think the museum setting today shapes our viewing experience compared to how it might have been received in Bloemaert's time? Editor: That’s a great point about the academies. Today, we might see the nudity as a statement on the body, but it sounds like then, it was more about demonstrating skill and adhering to established aesthetic standards within the art world. Does that limit the possible interpretations? Curator: Not limit, necessarily, but certainly inform. Consider also the politics of imagery. Depictions of Venus often carried political and social undertones related to patronage and societal ideals. Think about who had access to these images and the messages they were intended to convey. Perhaps reflecting on those original intentions would lead to different interpretations from today’s perspective. Editor: That’s fascinating, to think about how the socio-political context of art shapes what is depicted and also who views it. It really brings another layer of richness to the image. Curator: Precisely. Context is key. By looking at this drawing as both an object of beauty and a product of a particular time, we can gain a much deeper appreciation of its significance and Bloemaert's position within the artistic and social hierarchies of his day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.