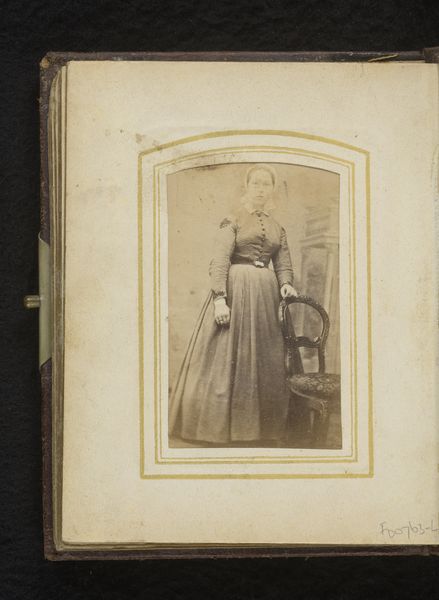

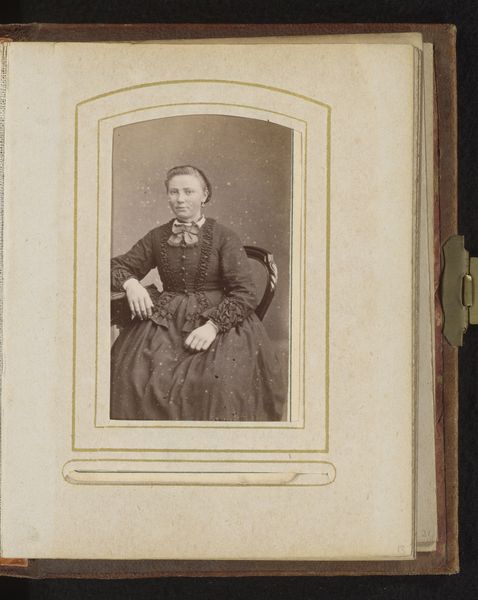

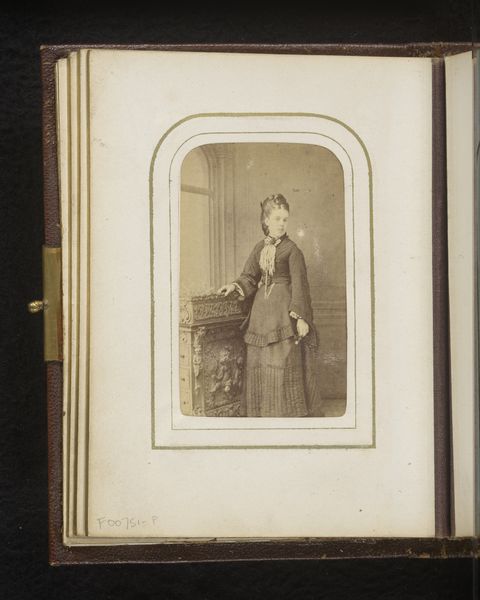

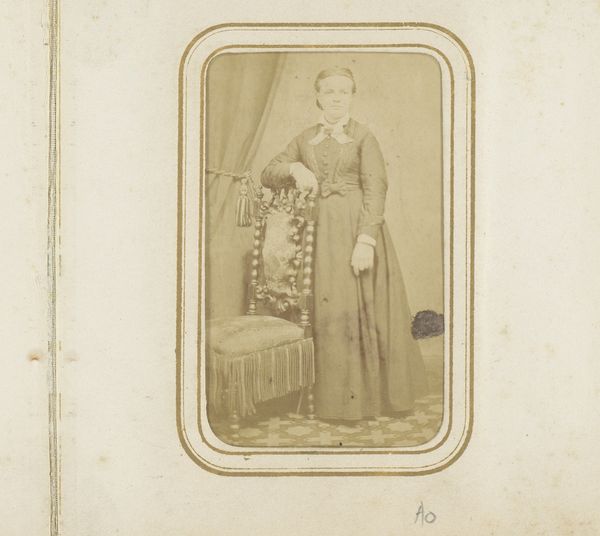

Portret van een staande vrouw, leunend op een vaas op een tafel 1865 - 1900

0:00

0:00

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This albumen print, "Portret van een staande vrouw, leunend op een vaas op een tafel" roughly translates to “Portrait of a standing woman, leaning on a vase on a table”. It's from somewhere between 1865 and 1900 and is attributed to Hermanus Jodocus Weesing. It's interesting, isn’t it, how these seemingly simple portraits can reveal so much about the subject’s social standing and the aesthetic sensibilities of the era? Editor: Yeah, there’s this melancholy mood. The lighting, that steely gaze… and she leans on this ornate prop with the blankest of expressions! Almost daring us to ask her anything. But look closer – those age spots add such strange character. What do you see? Curator: I see a carefully constructed performance of middle-class respectability. The woman's dress, the pose, the prop – all communicate a desire to be seen as refined and cultured. But I also see hints of constraint, perhaps even a subtle resistance to the roles imposed upon women of her time. She stands, rather than sits – not in compliance, necessarily. Editor: I feel that. And those sleeves – talk about power dressing. But what about that vase she is leaning on, literally and figuratively. Such a cliché, maybe? Though without it she's just... standing, period. Is it supposed to imbue her with education or class? Curator: Precisely. The vase and draped cloth are part of the visual language of 19th-century portraiture, symbols of wealth and status but also stand-ins, you see, that signal some connection to classical antiquity and learning. It elevates the subject beyond the mundane. Yet these props also highlight how the representation of women at this time could also be formulaic, trapped within narrow expectations. Editor: A gilded cage, photo style. It reminds me a bit of early theater with a female lead… But let's jump forward to today – does this make anyone reconsider how identity works in contemporary portraiture, online even? Filters, perfect angles, the whole works? Curator: Absolutely. By studying portraits like this, we can better understand the long history of how people have used images to shape and project their identities. Recognizing how certain visual conventions—poses, props, even the absence of a smile—functioned in the 19th century allows us to be more critical and self-aware about the visual messages we consume and produce today. There’s power in seeing then and now as interlinked! Editor: Very well said! Suddenly, that stern Victorian lady is all of us... or maybe none of us. Thanks for shaking me out of my contemporary perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.