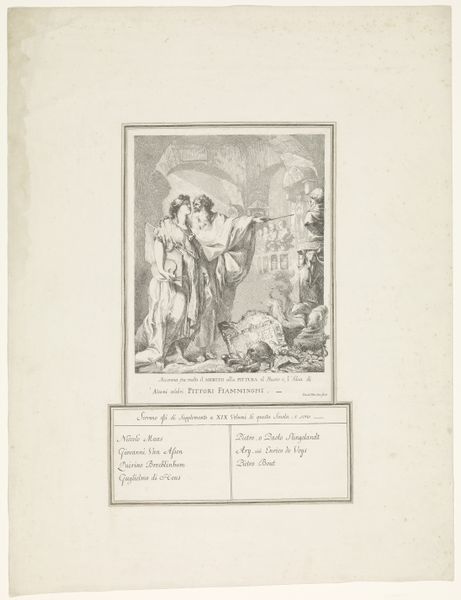

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 158 mm

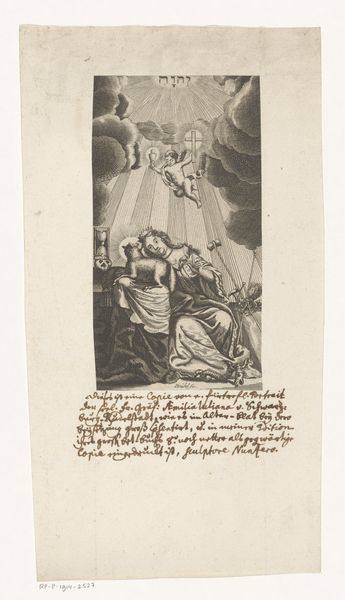

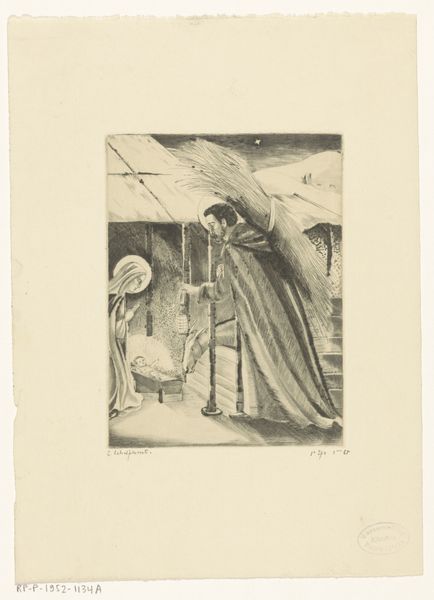

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Joachim en Anna," was created by Raffaello Schiaminossi in 1595. You can find it here at the Rijksmuseum. It depicts a meeting, perhaps a promise, charged with symbolic power. Editor: My immediate impression is one of stark contrast, like looking at an unfinished tapestry. The lines are so distinct, almost aggressively present. You can almost feel the pressure of the burin on the plate. Curator: Indeed. It's fascinating how the sharp, clean lines give such depth to what could otherwise feel like a very flat scene. Notice how the figures of Joachim and Anna are bathed in light emanating from above. In Christian iconography, Joachim and Anna are the parents of Mary. Their union, their embrace, signifies hope. It represents a pivotal moment when, despite their age and presumed infertility, they're blessed with the promise of new life. Editor: Yes, but let’s consider Schiaminossi's tools, his workspace. This wasn't some ethereal inspiration, but a craft. Imagine the physical labor of cutting those fine lines into the copper plate! Think about the societal value placed on printed images, and their capacity for mass distribution during this era. Was it purely devotion, or was there something also very much tangible, of an economic motivation behind its creation? Curator: A valid point. The printing press certainly democratized art in a way previously unimaginable. However, focusing purely on production overlooks the resonance of the scene itself. The yearning for offspring, the promise of divine favor – these are enduring human concerns reflected in the emotional exchange here. Look at Anna’s upturned face, the gesture of anticipation! It reflects hope but also long desire. Editor: And how many copies were made, and how much they circulated in that time? Engravings allowed access to religious imagery outside the confines of the Church. Were people posting this in their homes, mediating faith in a very material way, and shaping what could now be defined as middle-class devotional taste? The accessibility is, from my standpoint, the revolution. Curator: Both the intent behind creating these, the skilled execution of lines, and the method for spreading them seem inseparable for its message. Editor: Precisely. Seeing this print now through its craft brings into new light the symbolic message itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.