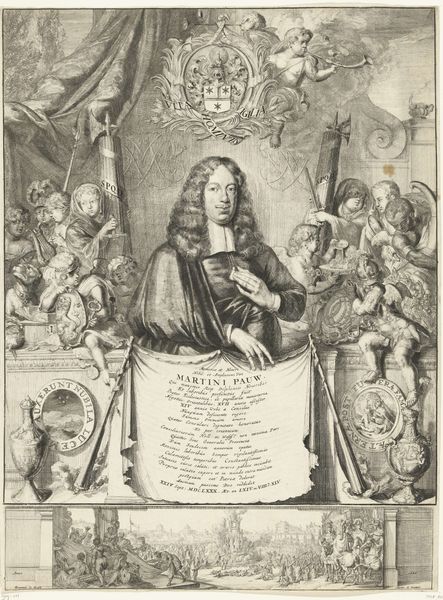

print, metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

metal

#

caricature

#

engraving

Dimensions: 514 mm (height) x 409 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: Welcome. Here we have a seventeenth-century print of Erik Hardenberg Gyldenstjerne by Albert Haelwegh. Likely completed between 1666 and 1672, this engraved portrait resides in the collection of the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. Editor: First impression? It’s got a *lot* going on! Almost chaotic. This fellow, Mr. Gyldenstjerne, is smack-dab in the center, looking rather composed, while allegorical figures jostle for attention around him. Curator: Indeed. These portraits were never *just* portraits. Consider how nobility was understood at this moment. Visual codes became powerful tools for projecting authority, lineage, virtue. The armor and classical figures certainly speak to a desire for such projection. Editor: Totally. Like they’re building him a legacy brick by brick. I wonder though, is the stiffness almost...funny? These guys straining to hold up his image while Erik gives us this stoic look! He looks like he’s saying, "Yes, this is *exactly* my life.” Curator: Remember the political realities. Gyldenstjerne served in prominent positions and later became a key negotiator between Denmark and Sweden. A portrait like this becomes a strategic piece of diplomacy. His achievements, represented here, aren't merely personal; they symbolize the strength and stability of the kingdom. Editor: Okay, okay, power dressing! But those figures—they feel kinda stilted, no? Maybe Haelwegh wasn't thrilled to be churning out another propaganda piece, or was he in on the joke too? Curator: A good question. The success of printmaking at the time hinged on its capacity for dissemination, its relative inexpensiveness, but also on the consistent application of iconography. Haelwegh's technical skill, rendering details in metal, gave widespread access to certain important figures, cementing and controlling their imagery in the public imagination. Editor: Right. So even if Haelwegh WAS making a sly commentary, he was mostly creating a version that resonated with power. It does make you think about what kind of ‘performance’ we're all putting on when a camera appears! Curator: Absolutely. Every image is, in a sense, a careful construction, especially then. The tension you sensed between genuine expression and stylized representation underscores that fundamental truth. Editor: I’ll leave with this thought. That even then artists were, in a way, negotiating truth, power, and just a dash of personal mischief. Curator: And Haelwegh gives us something to contemplate with this image, inviting us to look beyond the surface of the portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.