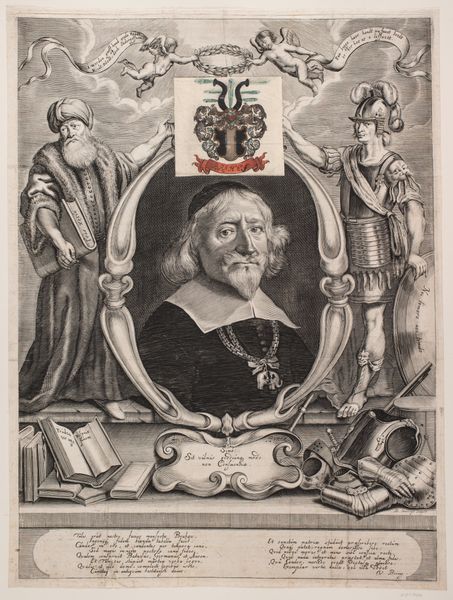

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 525 mm, width 393 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this engraving, "Portret van Christophor Urne met Minerva en Mars," created around 1660 by Albert Haelwegh. It's quite striking. Editor: Indeed! My initial impression is one of stately grandeur. The density of symbolic elements, the formal portraiture – it feels very performative. Curator: Precisely. Haelwegh uses rich symbolic language. We see Urne in the central portrait, framed by an oval inscribed with Latin text, flanked by allegorical figures: Minerva, goddess of wisdom, and Mars, god of war. The cherubs overhead further emphasize this complex visual statement. Editor: What's fascinating is how Urne, presumably a powerful man in his own right, is being explicitly linked to these archetypes. It's an active construction of identity and authority in a specific historical and political moment. We’re reminded of the influence classical antiquity still had on European power structures in the 17th century. Curator: The inclusion of Minerva and Mars represents not merely power, but a specific ideal of governance: wisdom and strategic force combined. Consider the book and scales beneath Minerva – she embodies learned judgment. It shows that war without reason leads to a dangerous society. Editor: And there's an inherent tension in juxtaposing those figures, isn't there? The image seems to negotiate this dichotomy, as if acknowledging the potential for conflict while ultimately advocating for balance under Urne’s leadership. The visual rhetoric here almost acts as propaganda. It can easily be critiqued, since most political leaders hardly adhere to this sort of idealism. Curator: This use of symbolism resonates across time. Portraits have always performed this role of communicating not just likeness, but aspirational qualities and desired attributes. It’s fascinating how these classical images take root again and again. Even now, in contemporary advertising, we can identify comparable use of cultural signs that try to give dignity or even trustworthiness. Editor: It is indeed. What does it reveal about Urne's perceived legitimacy and standing? It begs the question: does relying on pre-existing, almost 'universal', figures of authority risk making Urne himself seem interchangeable, his individuality subsumed into these long-established symbols? It's quite ironic when thinking about contemporary figureheads or celebrities whose persona is always so radically authentic or unique. Curator: That’s an interesting point. I suppose what fascinates me most is the persistent, universal human need to invest in symbolic language for defining not only power but also selfhood and status. We all engage in this form of meaning making; and seeing how figures in the past communicated it teaches us much about its persistent qualities. Editor: Agreed. And questioning how we interpret these loaded visuals enables us to be aware about who and what shapes our cultural understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.