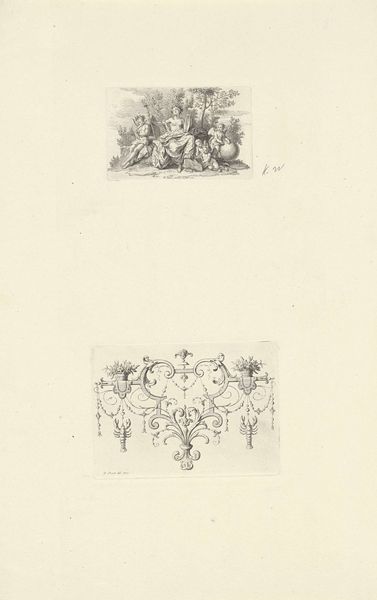

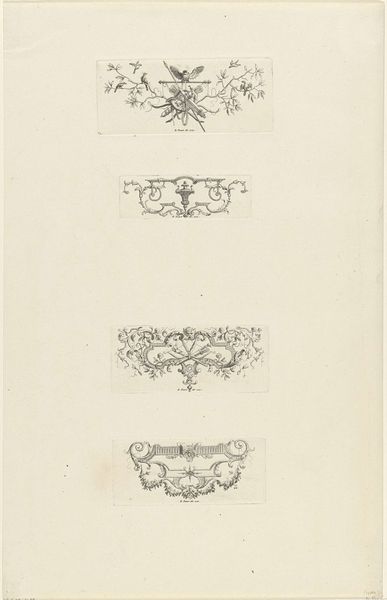

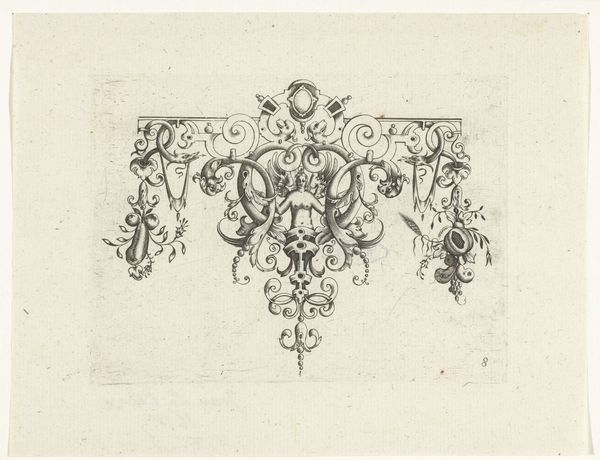

Takken / Afgunst in ornament met slangen / Geopend graf in kader van bladranken 1683 - 1733

0:00

0:00

bernardpicart

Rijksmuseum

drawing, ornament, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

ornament

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

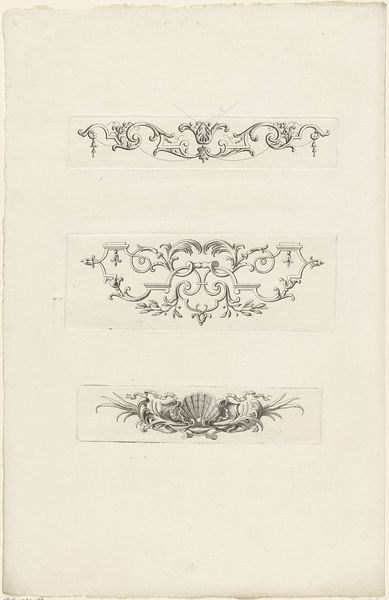

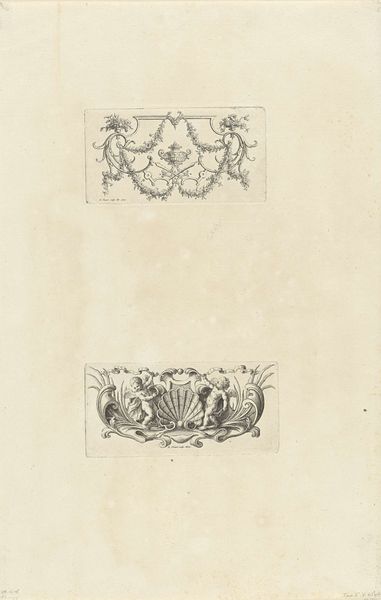

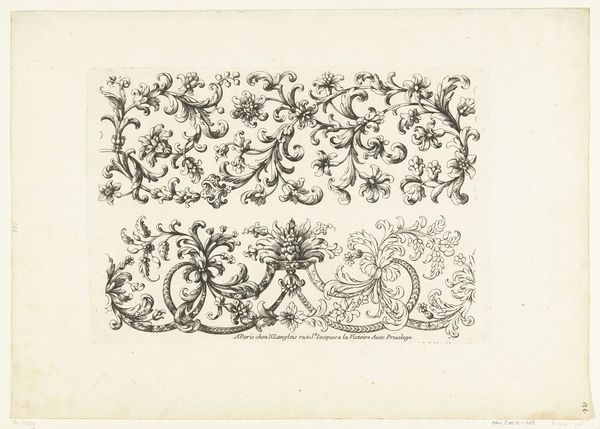

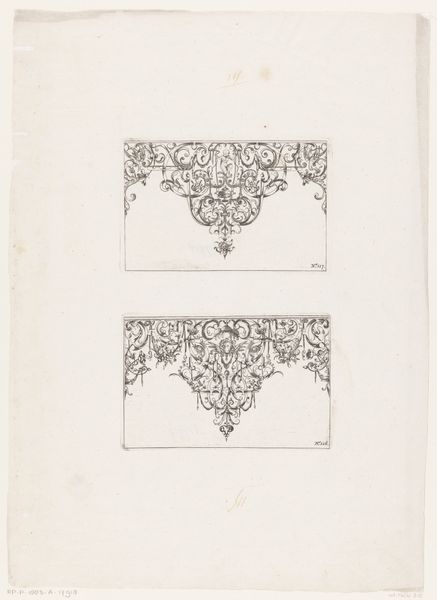

Dimensions: height 381 mm, width 244 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

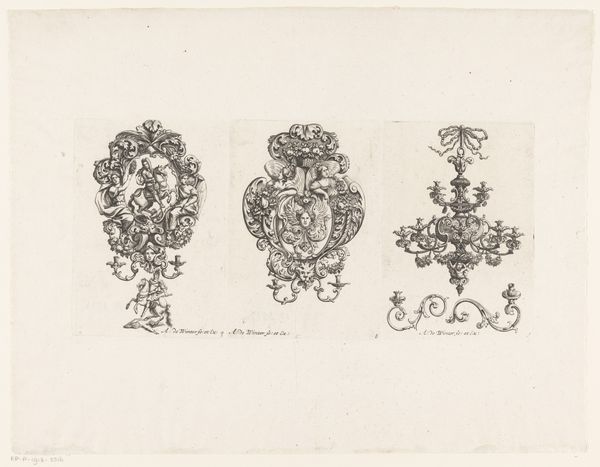

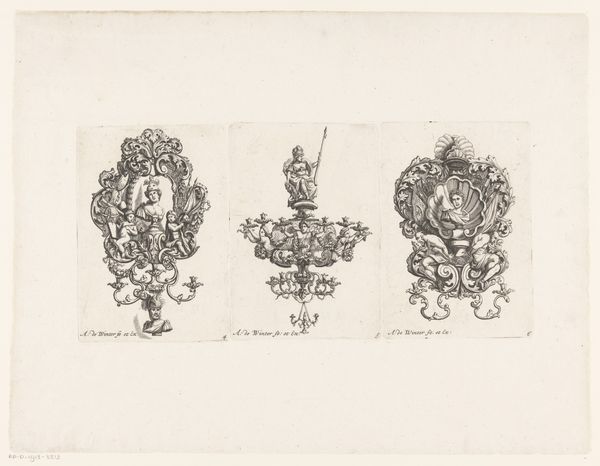

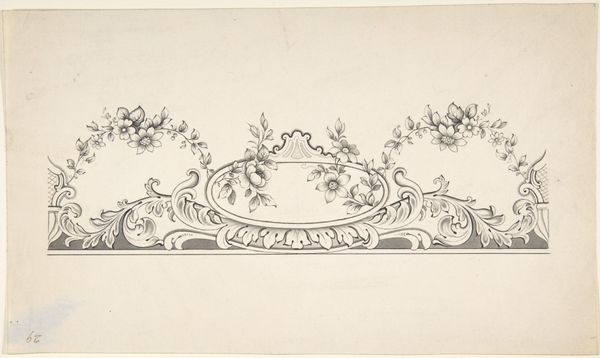

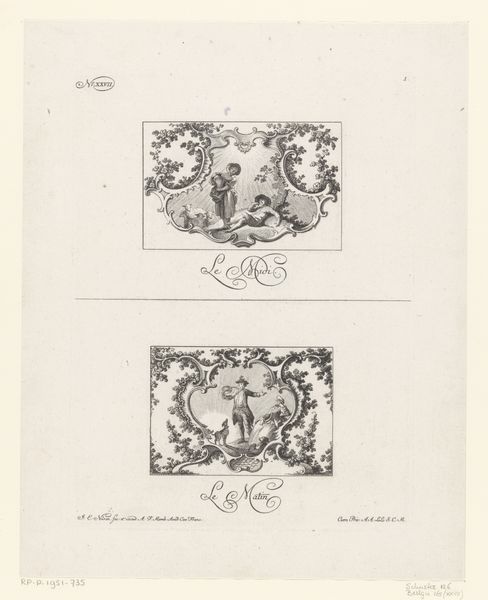

Curator: Here we have a print by Bernard Picart, made sometime between 1683 and 1733. The full title is "Takken / Afgunst in ornament met slangen / Geopend graf in kader van bladranken," or roughly translated, "Branches / Envy in ornament with snakes / Open grave in frame of leaf vines." Editor: My first thought is that it’s unsettling. There's a dark whimsy, and despite the delicate lines, I can’t shake a feeling of disquiet. It looks like a heraldic design gone wrong. Curator: Yes, that tension is crucial. The baroque period loved ornamentation, but this piece subverts its traditional joyousness. Consider the engraving technique, for instance; the density and precision of line create an unsettling texture. Semiotically, snakes, open graves—they all function as signs pointing away from the purely decorative. Editor: Exactly. The snakes evoke ideas of deceit, the grave—mortality. But why frame them within this elaborate ornamental style? Doesn't the inclusion of envy challenge any potential patron, prompting us to question societal power structures or the dangers inherent in vanity? Curator: Indeed, its sociopolitical implications are hard to ignore. These are common concepts found in emblem books and moralizing prints. Picart seems to be acknowledging those tropes while also playing with the viewer's expectation of pleasure, inherent in ornament, to create something intentionally disturbing. Look, in the middle register, the figure holds what looks like winged moneybags. Are these intended to act as satire? Editor: Undoubtedly. Picart gives the viewer beauty on the one hand, critique on the other. Its power resides in that duality, I think. Picart's artwork exists within a historical context marked by great social inequalities, class stratification, gender roles, religious struggles, economic anxieties and other big life problems, and seems ripe for our interrogation. Curator: An excellent point. Seeing it displayed at the Rijksmuseum among more conventional works gives it even greater resonance, no? It prompts one to consider how seemingly decorative works can be incredibly layered and meaningful. Editor: Absolutely. It reminds us that art is rarely just beautiful—it's a conversation, sometimes an argument, happening across centuries. And maybe, the unease is the point. It sticks with you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.