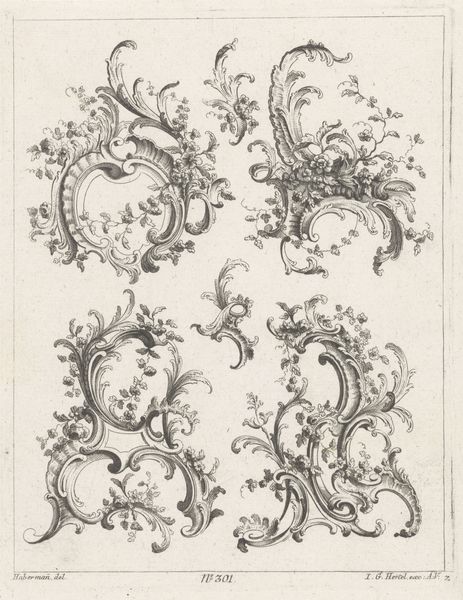

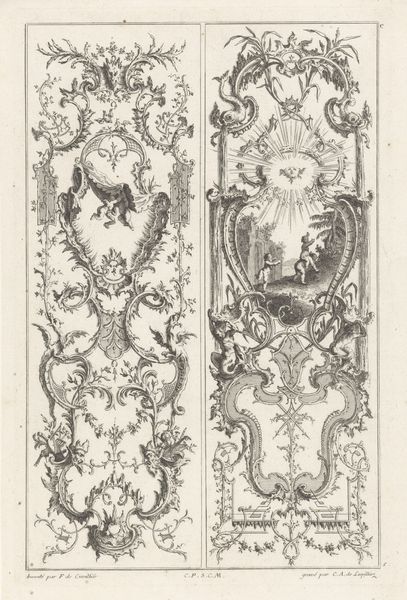

print, engraving

# print

#

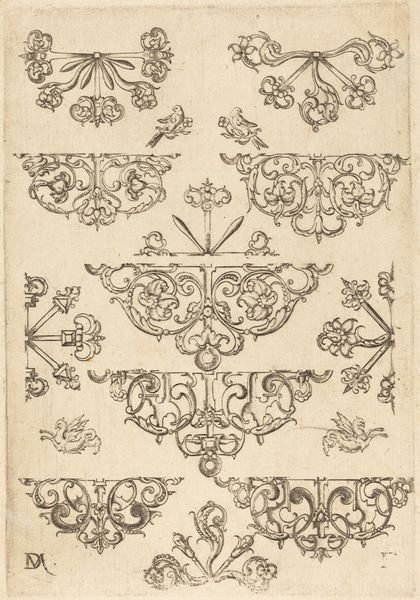

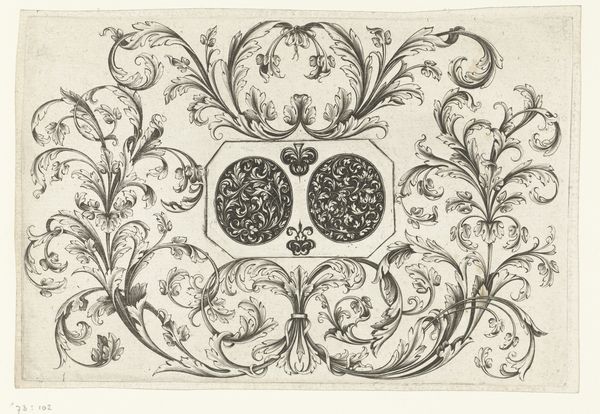

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

#

rococo

Dimensions: height 255 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today we’re looking at “Rocailles,” an engraving made sometime between 1731 and 1775. The print is currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is one of ornate elegance, I'm immediately struck by its potential as templates or stencils, hinting at repeated production. The swirls and flora dance in a composition of sophisticated frivolity. Curator: Precisely! These designs served as models for artisans and craftspeople. Consider the labour involved. The meticulous etching on the copper plate by I.G. Hertel, after a design by Haberman, was skilled piece-work meant for larger-scale application. This challenges the romantic idea of the singular, genius artist. Editor: Right. And if we consider the Rococo style—with its roots in aristocracy, it's inextricably linked to power structures. Who were the consumers of such intricately ornamented objects? It speaks of the lavish expenditure enjoyed by the few, funded by often invisible, exploited labour. The asymmetry and curves mirror social disequilibrium, perhaps. Curator: I agree that these kinds of ornamentations would not exist without exploitation, and their material value reinforces an unevenly distributed socioeconomic hierarchy. Beyond their overt visual appeal and association with elite consumerism, consider that their actual usage often took place within similarly ornamented spaces that would be designed and fabricated with collaborative processes across numerous artists and manufacturers. Editor: I’m thinking about access—or, rather, lack thereof. Designs like these, translated into silverwork or furniture, became potent signifiers of class. The intricate details and the materials themselves served to exclude, reinforcing social boundaries. It is quite a loaded piece in such an efficient design. Curator: And the reproductive nature of printmaking meant this level of ornamentation was circulated for widespread use by craftspeople—bridging high design and more accessible production methods. Editor: Definitely. A tension emerges. Intended to inspire elite craftsmanship, yet disseminated, blurring those sharp divides—if only slightly. So we’re really seeing not just a design, but a visualization of complex socio-economic dynamics at play. Curator: It certainly invites reflection on the complex material realities underlying visual and design culture of the 18th century. Editor: Absolutely. Makes you reconsider the glittering surfaces, doesn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.