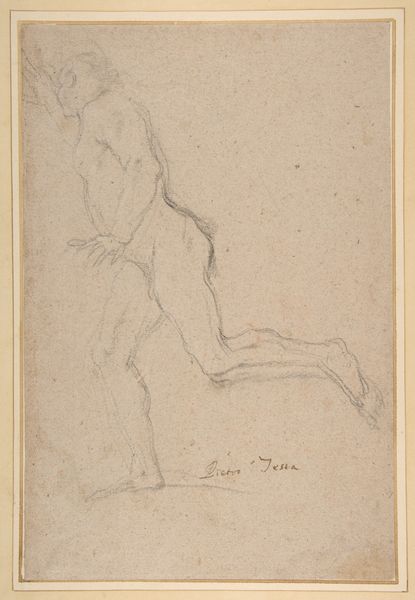

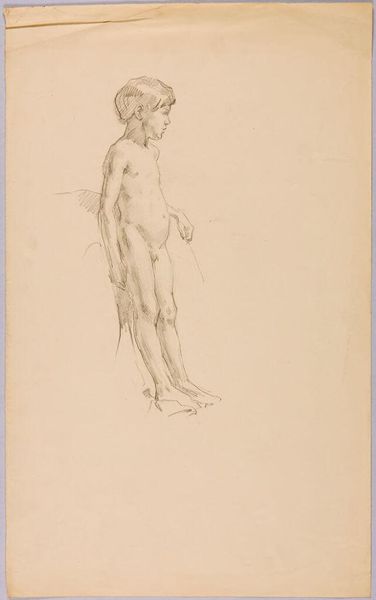

Dimensions: support: 252 x 180 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

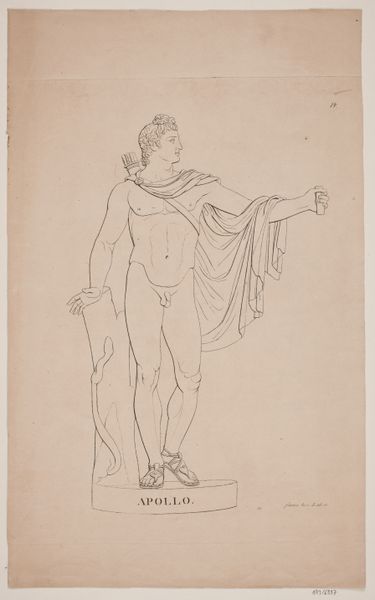

Curator: The artwork before us is Giles Hussey's "Apollo Belvedere," a pencil drawing from the 18th century. Editor: It’s ghostly! The pale figure seems to float off the page; there's a distinct lack of density. Curator: Precisely. Hussey was quite interested in developing proportional systems; notice the inscription mentioning a "Machine to take the Ease of Proportion." This piece reveals his intense focus on the mechanics of representation. Editor: So, less about divine beauty, more about the construction of ideals? I wonder how this focus intersects with the social structures of the time, the inherent biases in defining "ideal" forms, especially a male nude. Curator: I think you're right to push us to consider the power dynamics at play. Hussey’s drawing, in its very process, reflects the act of dissecting and categorizing beauty. Editor: It certainly gives me a lot to think about regarding the historical context of beauty standards. Curator: Indeed, and it invites us to consider how such ideals continue to affect our understanding of the human form.

Comments

tate 10 months ago

⋮

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hussey-apollo-belvedere-t08219

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Hussey probably made this copy of the famous Hellenistic statue while he was in Italy during the 1730s. His ability to draw such controlled continuous lines was no doubt aided by the 'machino' mentioned in the inscription, which may have been a perspective machine. There were a number of such devices used at this time, like the perspectograph, which enabled the artist to trace a subject through the use of a special eye-piece and a system of upright rods and pulleys. Hussey's commitment to portraying exact likeness in his work is evident in a contemporary description of him as 'eager to crown his art with the most conceivable perfection'. Gallery label, August 2004