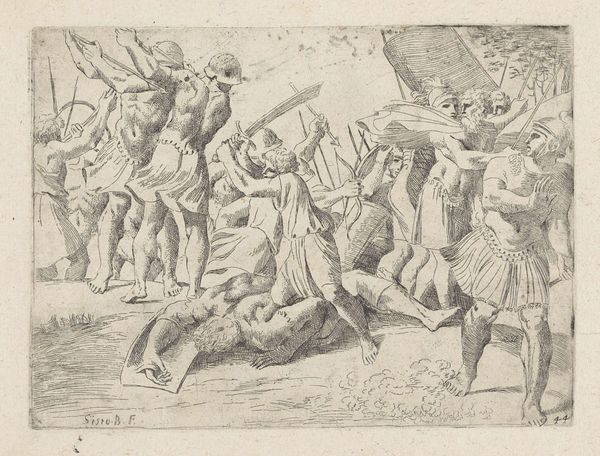

print, etching

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

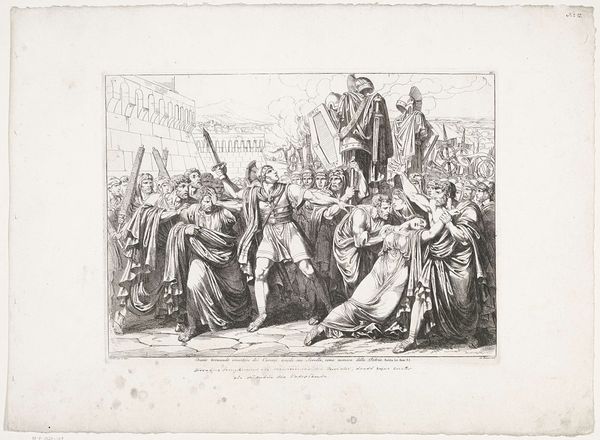

Editor: This is "Salomo door Sadoc tot koning gezalfd," or "Solomon Anointed King by Zadok," an etching by Orazio Borgianni from 1615. It's incredibly detailed for a print! All those tiny lines building up the scene give it so much energy. How would you interpret it? Curator: What I notice first is the physicality of the etching process itself. Look at the varying line weights and densities. The artist has manipulated the copper plate through acid-resist techniques, revealing an intricate layering of labor. And the print, as a multiple, democratizes the image, taking a religious scene from the elite realm into potentially wider circulation. Editor: So, the medium itself is part of the meaning? I hadn't considered that. Curator: Absolutely! Etching in the 17th century wasn’t just a means of reproduction; it was a commercial activity and a mode of distributing ideas. What social structures supported Borgianni in making this work? Who was buying it, and why? These questions open a fascinating material history. Consider how the paper was made, how the ink was formulated… Editor: That's a really different perspective than I'm used to. It almost feels like an art history of making, instead of just looking! Curator: Precisely! By focusing on the means of production, on materials and consumption, we shift the narrative away from simply aesthetic appreciation. It prompts us to explore the economic and social context of art. Editor: I get it now. The materiality provides tangible entry points for examining the societal conditions around its creation. Curator: Indeed. It offers us the chance to reconsider power structures inherent not just in the subject matter but also in the act of artistic production itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.