drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

ink painting

# print

#

etching

#

classical-realism

#

paper

#

ink

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 12 3/4 × 8 7/8 in. (32.39 × 22.54 cm) (plate)17 3/4 × 11 1/8 in. (45.09 × 28.26 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

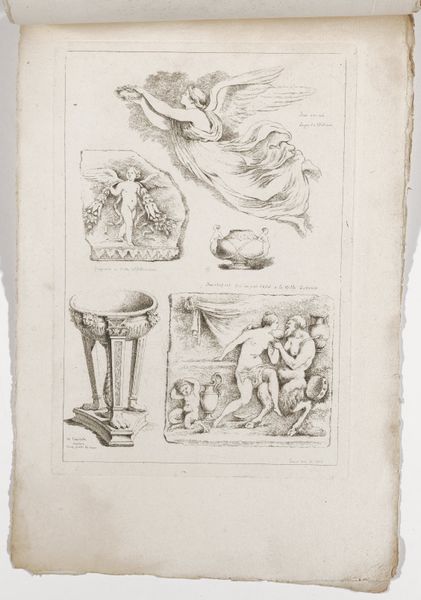

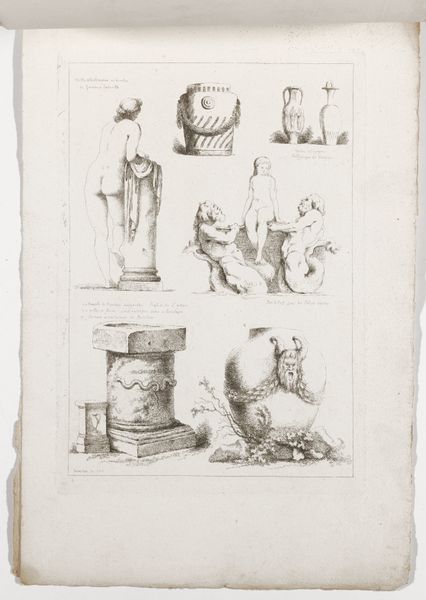

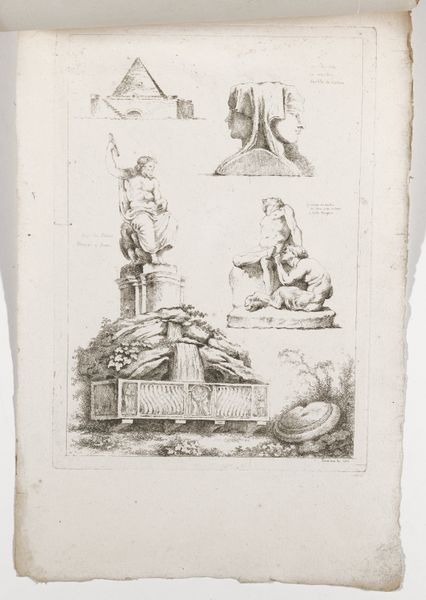

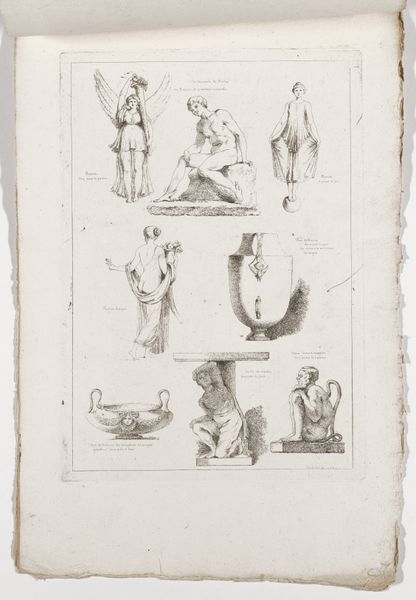

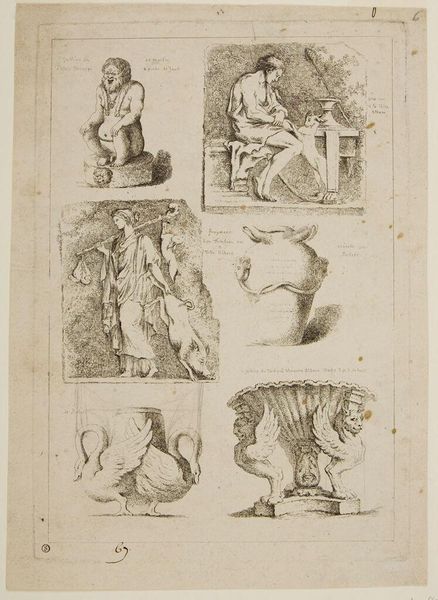

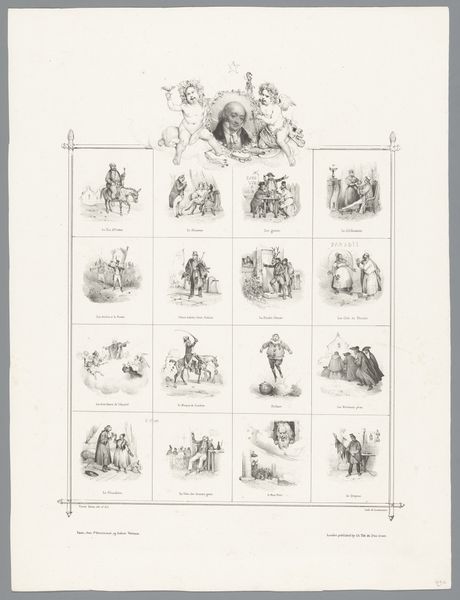

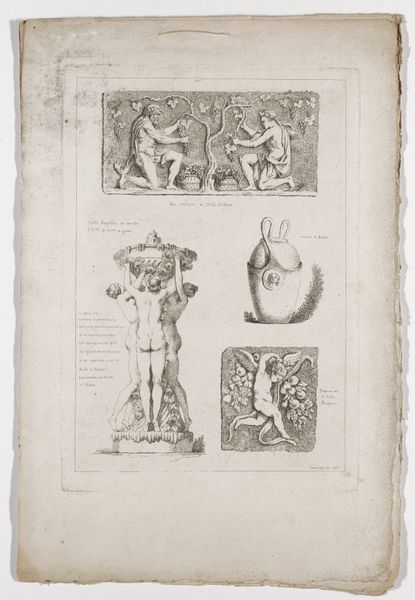

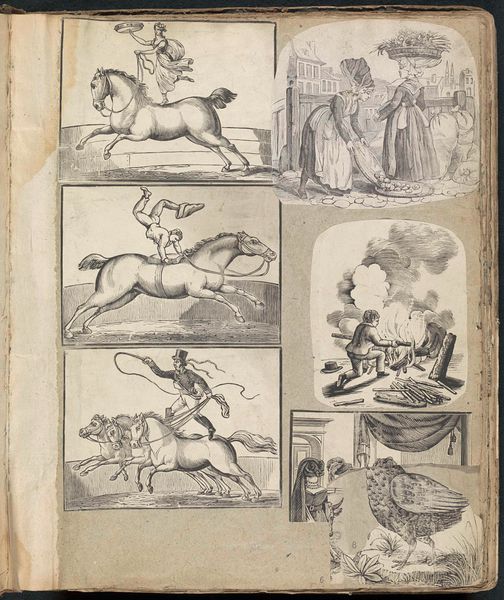

Curator: Oh, what a curious spread! Is this a page from a sketchbook, or maybe an encyclopedia? Editor: Indeed! We are looking at "Fascicule III," created in 1763 by Jean Claude Richard, Abbé de Saint-Non. It's an etching in ink on paper. Curator: It's fascinating how the artist compiled so many seemingly unrelated sketches onto one page. There's a figure hunched over what looks like a grindstone, various Grecian-style urns, even a goddess figure. There's almost an archaeological feel, like looking at fragmented memories. Editor: Yes, there’s a compilation aesthetic at play. Each vignette acts as its own study. Thinking about the etching process, the artist would've labored over each individual plate for the separate components. How might these individual studies have been combined? Curator: That's an interesting consideration... perhaps this piece reflects the artist's stream of consciousness, showcasing whatever subjects captured his fancy at the time. Maybe it echoes the cabinet of curiosities popular in the 18th century, compiling random items that represent something significant. Editor: And consider how widely disseminated prints like this would have been, and the types of patronage or audiences it appealed to. These detailed sketches are themselves commodities that could be circulated throughout the artistic landscape. Curator: Absolutely! Prints democratized art in a way never seen before. Thinking about that, it lends an interesting angle to those urns on the page—suddenly, they're not just objects d'art, but prototypes, mass-produced objects that were consumed by different tiers of patrons and the masses. Editor: A provocative reflection, I concur. This ink etching offers a window into not just artistic practice, but also systems of labor and consumption of aesthetic taste in 18th century Europe. Curator: It does! Each detail seems to invite an investigation. A fascinating journey that makes me question assumptions about art, beauty, and who gets to consume what. Editor: Precisely. The value isn't solely aesthetic—it’s bound to the historical record.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The Jean-Baptiste Claude Richard (also known by his title abbé Saint-Non) embodied the important role of the amateur, an patron and connoisseur of the arts as well as a practitioner in 18th-century France. He was a skilled networker, a curious, innovative printmaker, and he supported his artist friends in their projects and travels. Saint-Non executed this suite of prints in Paris in 1763, representing antique fragments and reliefs he saw during his travels in Italy from 1759 to 1761. Most of the monuments are identified in the inscriptions by their locations in Rome. The works reflect French artists’ fascination with antiquity at the time, and the way in which these sources were transmitted to a larger public through the circulation of prints. Remarkably the suite of etchings remain as originally issued, in three groups of six deckle-edged sheets stitched together simply along the top edge.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.