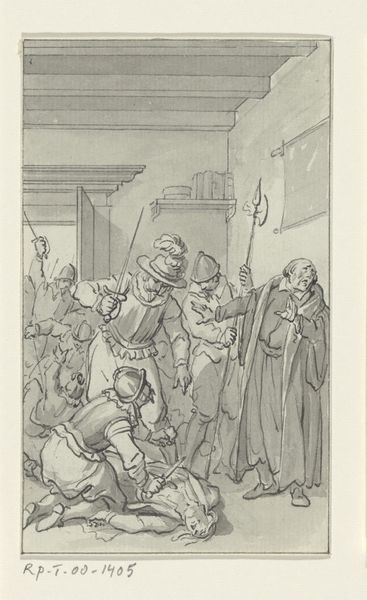

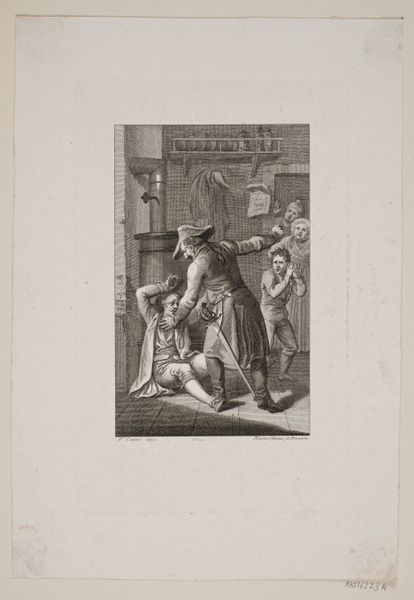

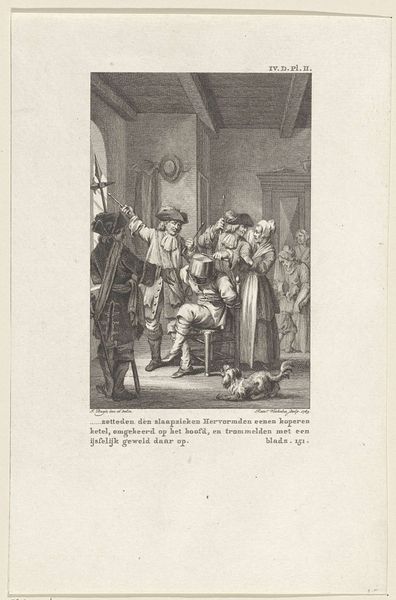

De zoon van L. Hortensius gedood en verminkt door de Spanjaarden, 1572 1790

reiniervinkeles

Rijksmuseum

comic strip sketch

light pencil work

pencil sketch

old engraving style

joyful generate happy emotion

personal sketchbook

idea generation sketch

sketchbook drawing

pencil work

storyboard and sketchbook work

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "De zoon van L. Hortensius gedood en verminkt door de Spanjaarden, 1572" by Reinier Vinkeles, created in 1790. It’s currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It looks like an engraving or etching, depicting a violent scene. What strikes me is how posed everyone seems despite the brutality. What's your interpretation? Curator: It's fascinating how Vinkeles, though creating this image in 1790, looks back to 1572, a critical moment during the Dutch Revolt. The depiction of the son of L. Hortensius being murdered and mutilated by the Spanish forces resonates with historical trauma. Consider this: How might Vinkeles be using this historical event to speak to the political tensions of his own time? Do you notice how the characters' clothing creates distinctions of power, and how power is expressed? Editor: I see how the Spanish soldiers have armor and elaborate clothing, setting them apart from the victim. It makes them appear more imposing, almost alien. Curator: Exactly. And what about the single cleric on the right of the frame? He's raising his right arm in a theatrical pose while wearing fancy robes; notice how he occupies as much compositional real estate as all of the armored men on the left. He’s not actively participating in the violence, but his presence implies complicity. How does this detail contribute to your understanding of the scene's broader context? Editor: So, it’s not just a depiction of violence, it’s a statement about the church's role in colonial violence? Curator: Precisely. By focusing on the son’s murder and the implied sanction by religious authorities, Vinkeles forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about power, authority, and resistance during times of conflict. Does understanding this context change your initial perception of the artwork’s composition? Editor: Absolutely, I'd initially perceived the characters' poses as awkward. Now, I recognize them as strategic devices in illustrating the power dynamics during periods of war and occupation. Curator: It's crucial to always question who benefits from particular narratives, and how they shape our collective memory of historical injustices. Editor: Thank you, I appreciate you bringing those narratives to light. Curator: And I value you continuing the narrative with engagement and critical thinking!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.