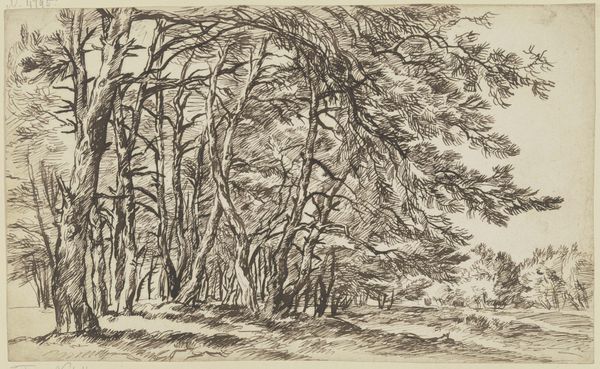

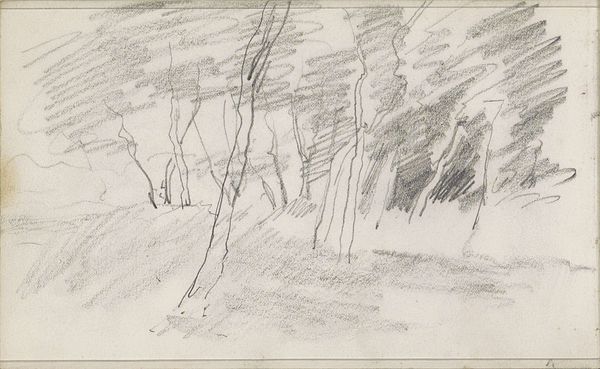

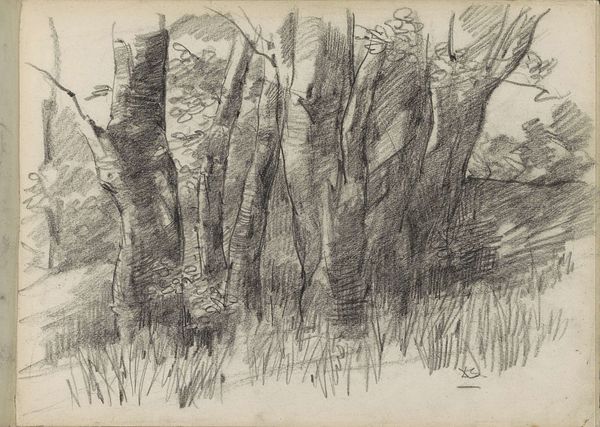

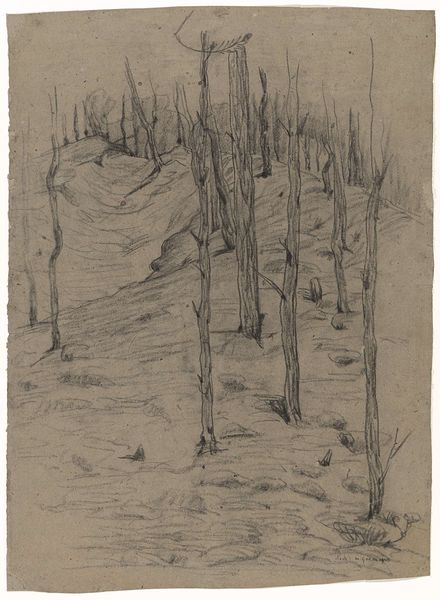

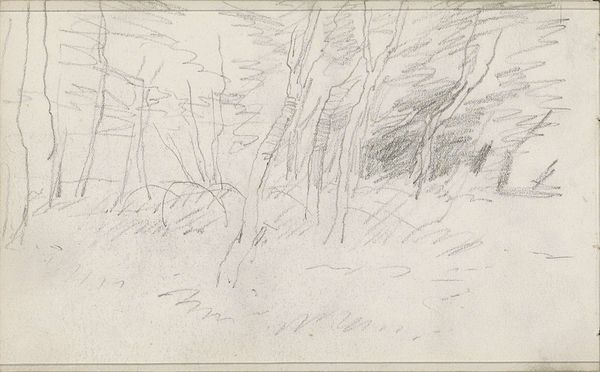

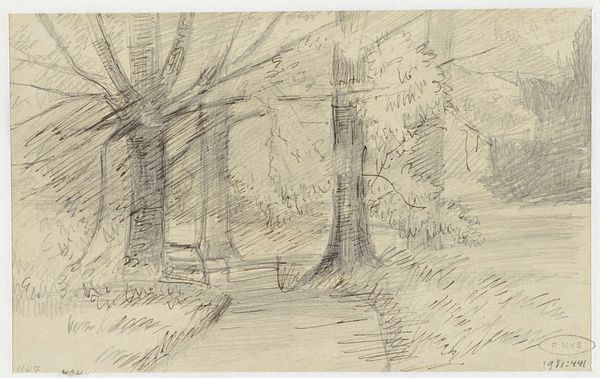

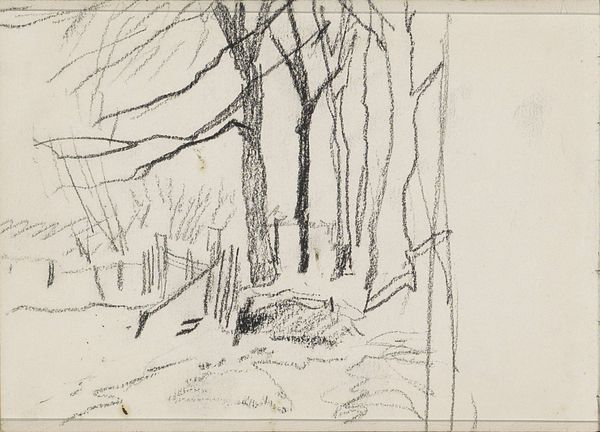

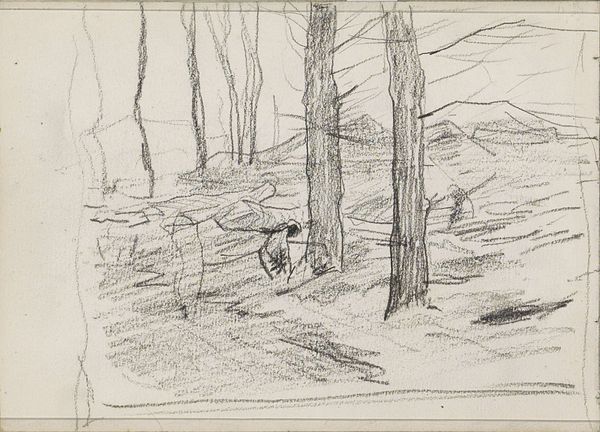

drawing, charcoal

#

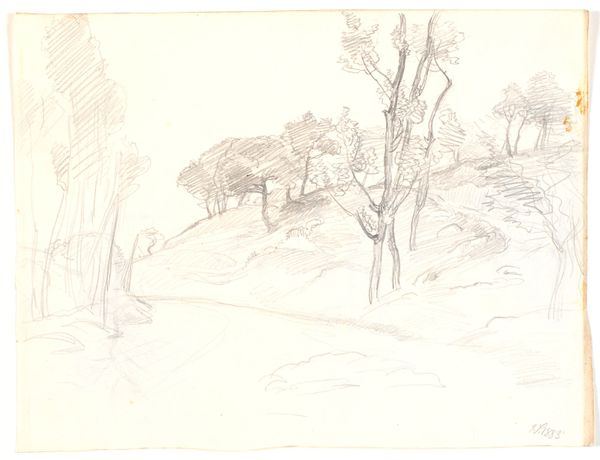

drawing

#

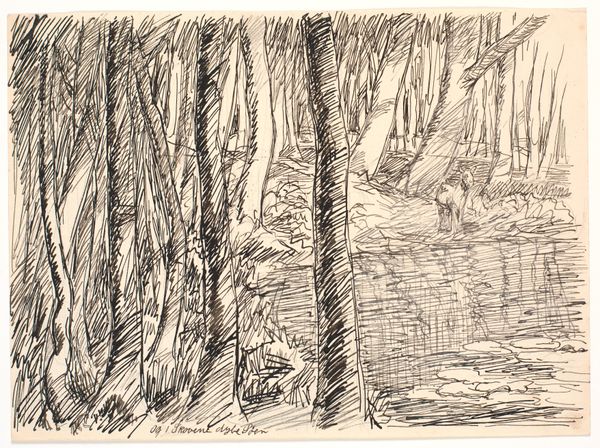

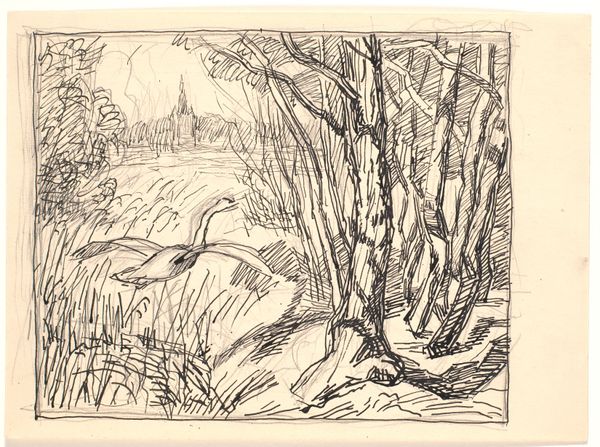

pen sketch

#

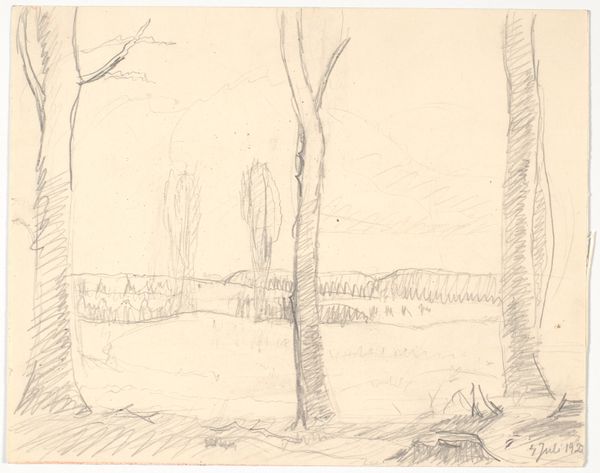

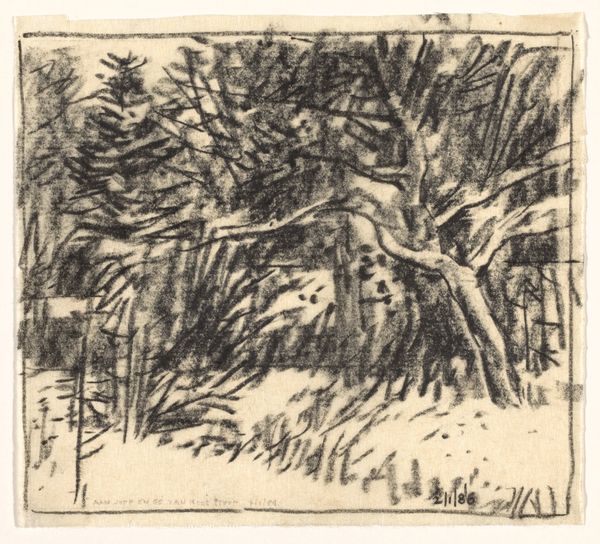

landscape

#

charcoal

#

realism

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 143 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's discuss Anton Mauve’s "Boslandschap," created sometime between 1848 and 1888. It's currently housed right here at the Rijksmuseum, rendered in charcoal and drawing materials. Editor: Mmm, feels melancholy. I'm immediately drawn into this little patch of bare trees, like the breath of winter's sigh frozen on paper. It has that stark feeling of transience, like something deeply personal about to disappear. Curator: Absolutely. The medium itself underscores this. As a realist landscape, "Boslandschap" speaks to a specific socio-historical yearning—a desire to authentically capture the raw, unvarnished reality of the rural landscape amid rapid industrialization. Mauve engages with the changing relationship between humans and the natural world during that period. Editor: Right. There's an undercurrent of social commentary too, that feeling of dispossession and detachment… Look how starkly rendered it is. The sharp charcoal feels brutal; it doesn’t romanticize the subject at all, which is rare for that time, I think. Curator: It's key to understand Mauve’s context. His exploration aligns with larger anxieties around the impact of industrial progress on working-class communities that lived close to the land. The piece almost dares you to look past pretty aesthetics. Editor: You said it! I think he perfectly captured that bleak rawness. It almost transcends its literal depiction – becomes something larger. What do you suppose he hoped to evoke with that sort of stripped-down intimacy? Curator: In the broadest terms, "Boslandschap" reflects evolving constructions of identity during a period defined by radical socioeconomic change. By depicting these desolate scenes, he makes visible those populations marginalized by dominant power structures, almost giving a voice to a silent demographic. Editor: Beautifully put. I think I see it a bit differently now... Thanks for untangling the deeper social strings running through these seemingly barren woods. Curator: It was my pleasure. Context allows us to expand our own interpretations and see new stories unfolding from art. Editor: Yes! To let the landscape reflect back the humanity of those who lived among it... It’s about reminding us we are bound to that history and those people. It still moves me, every time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.