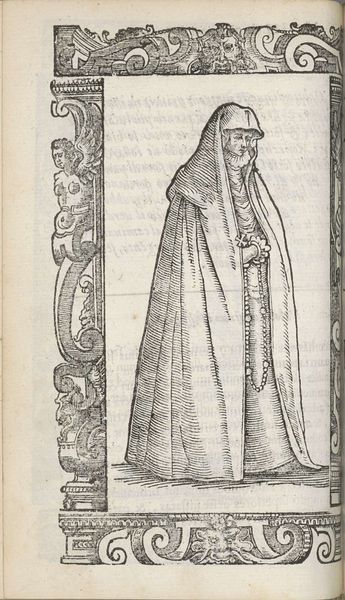

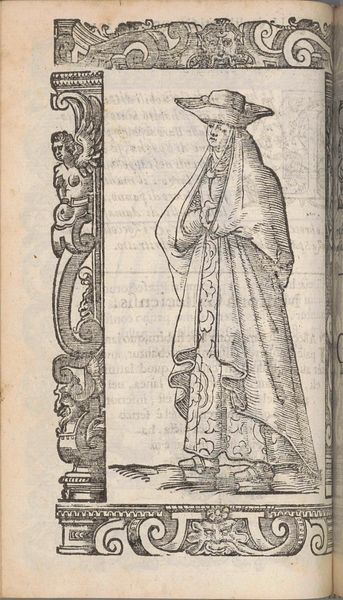

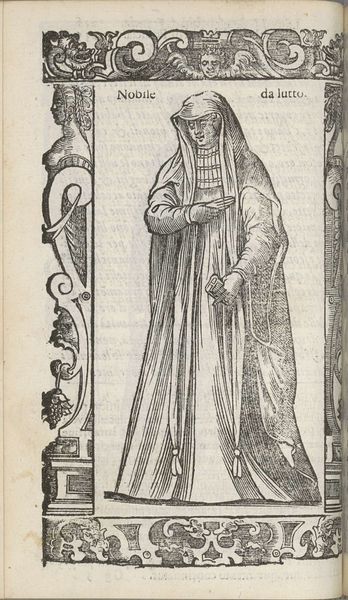

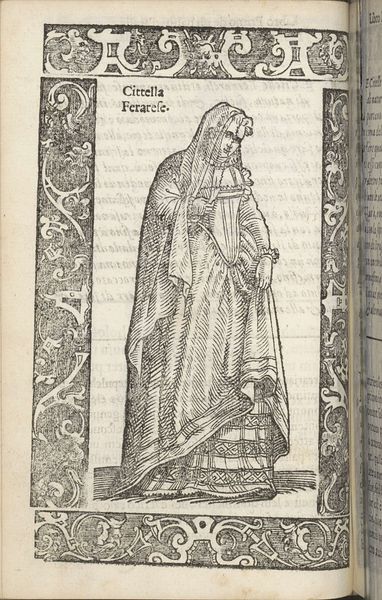

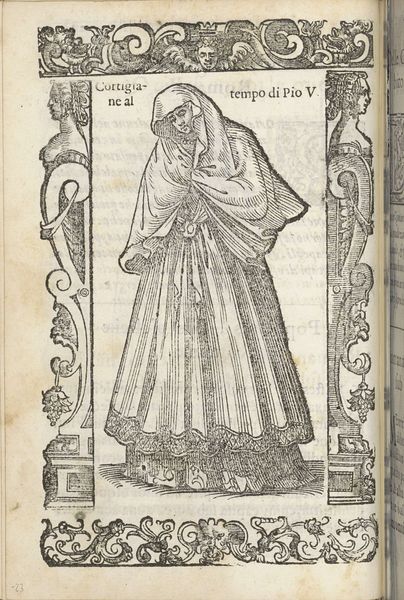

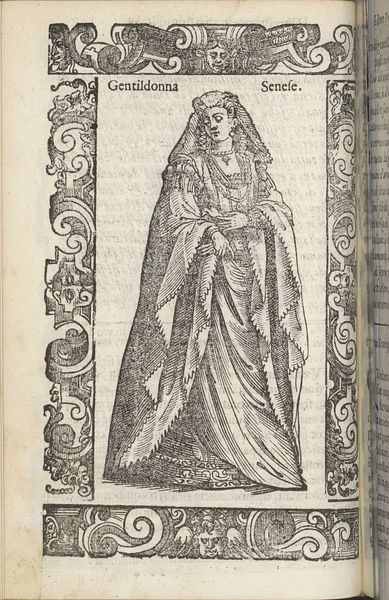

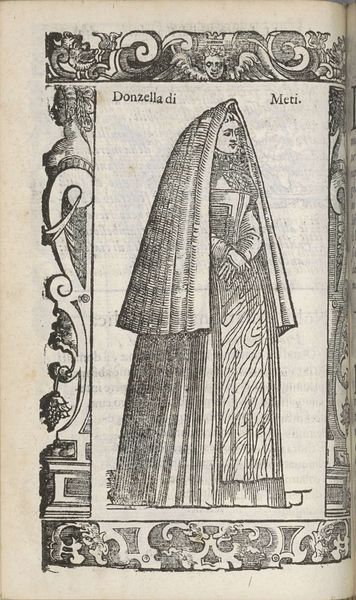

drawing, print, ink, pen, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

pen drawing

# print

#

ink

#

pen

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Donzella di Spagna," a pen and ink drawing from 1598 by Christoph Krieger. It has an intriguing stillness. What layers do you see when you look at it? Curator: I see a meditation on the veiled woman in 16th-century Spain. Krieger gives us more than just an image; he presents a social text. Consider the cultural constraints imposed upon women, their visibility deliberately diminished. What does the veil signify here? Is it solely about religious devotion or also about social control, the confinement of female agency within patriarchal structures? Editor: So the rosary she’s holding isn’t just a symbol of piety, but also perhaps a sign of the limited options available to women at that time? Curator: Precisely. The rosary becomes an emblem of their prescribed role. And what about the title itself, "Donzella di Spagna?" It implies a certain status, unmarried, pure, available… or not. It frames the subject, reducing her identity to a set of social expectations. Krieger gives us this drawing. How do we reclaim her narrative? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t considered how much the social context dictates how we view this drawing. Now it feels charged with all these unspoken layers. Curator: Art allows us to delve deeper into intersectional stories, connecting historical objectification to contemporary debates about agency and representation. Every line becomes a question. Editor: I’ll definitely look at art, especially portraits, in a new light now. Thanks for your perspective. Curator: My pleasure. Art’s power is in its capacity to spark dialogue and to unearth the hidden narratives within.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.