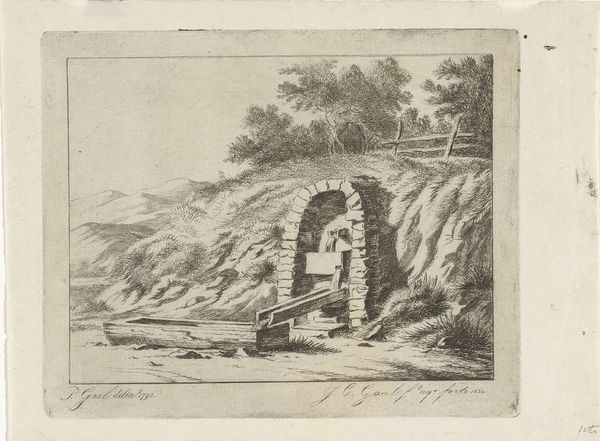

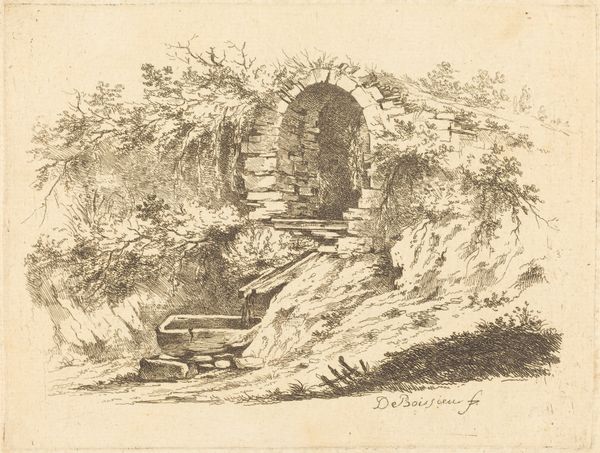

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

realism

Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 202 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

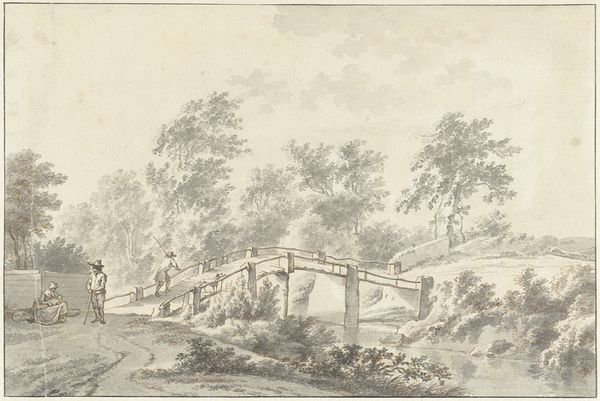

Editor: Charles Rochussen's "Brug," created in 1842, is a captivating etching. The scene appears quite rustic, focusing on what seems to be a small bridge or tunnel entrance. The details are remarkable given it’s a print. What draws your attention in terms of its material presence and the context of its production? Curator: The first thing that strikes me is the raw, almost unrefined quality of the etching. Look at the lines, the way they create texture – the grass, the stones. This isn't about idealized beauty; it's about the physical reality of this structure. The means of production become foregrounded, we are directly engaging with the marks and labor involved in creating this image. Editor: It almost feels… utilitarian? The bridge seems very functional, lacking any ornamentation. Curator: Precisely. Consider the social context: 1842. Industrialization is burgeoning, yet here is Rochussen focused on something very humble, made of earth, stone, and roughly hewn timber. What purpose did such an infrastructure serve for the laboring classes? Editor: I see, the emphasis on function rather than form reflects a different set of values, where the process of building and using this structure might be more important than its aesthetic appeal. Curator: Exactly. How does this image engage with contemporary society, think of it as challenging the traditional separation between "high" art and the work involved in building, labor, and consumption within everyday life? The very act of making a print makes it accessible to a wider audience, shifting away from the preciousness of unique artworks. Editor: So, instead of just seeing a pretty picture, we are being asked to think about who made the bridge, who uses it, and how art can be a record of those processes? Curator: Yes. It prompts us to consider art as a product tied to the means and modes of production. The “Brug” here might then be seen as more than just a scene, but evidence and record of everyday labor. Editor: This materialist perspective really brings a new level of appreciation. I never considered looking at landscapes in terms of their means of production! Curator: Exactly! Now you're engaging with the materiality of art history itself!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.