drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

dutch-golden-age

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

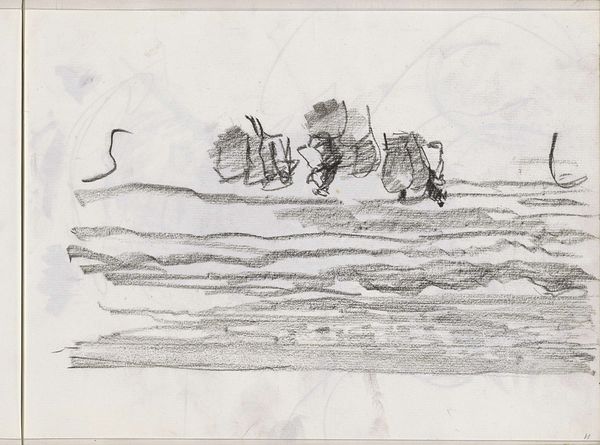

Curator: Before us, we have Anton Mauve's pencil drawing, "Boerin met een lam in een weiland," placing us somewhere between 1848 and 1888. The Rijksmuseum safeguards this simple rendering. What impressions strike you upon first sight? Editor: Hmm, ghostly. The figures feel light, about to lift right off the paper. It's as though a memory of a shepherdess, just a brief observation jotted down. Curator: "Brief" is apt, given Mauve’s Impressionistic leanings—though he grounded himself in Dutch realism. Beyond being a landscape genre scene, there’s the obvious symbolism of a lamb – tenderness, innocence – guarded by a woman. Does that resonate further, historically or otherwise? Editor: Lambs in art carry echoes. Early Christian art, the lamb as Christ, sacrifice, gentleness… and woman, naturally equated with nurture. Mauve was smart enough not to overstate this though, that simple scene speaks volumes. What do you suppose the act of choosing pencil offers in such scenes, as a tool of this particular artistic period? Curator: I sense a directness, a wish for authenticity, you know? Pencil allows immediacy. Brushstrokes might have given it too much romantic flair. Think also about availability and price; artworks like this were often quickly made in preparation for larger oil paintings. In any case, something genuine emerges, pure. Editor: Pure. I think I understand. Not overly constructed. And perhaps in its simplicity, it offers access. Everyone understands the basic relationship: human and animal, care and dependence. It translates culturally, spanning even now. What did he mean to depict exactly? Was he successful? Curator: As a glimpse into rural life through a soft, almost faded lens, yes, very much so. We find beauty not in detailed form, but through essential feeling, even raw observation, maybe even lost memory. Editor: Lost memory. Exactly. A whisper of something universally human. The choice of the simplicity makes it something anyone could observe, or experience, the kind of timeless image worth preserving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.