drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

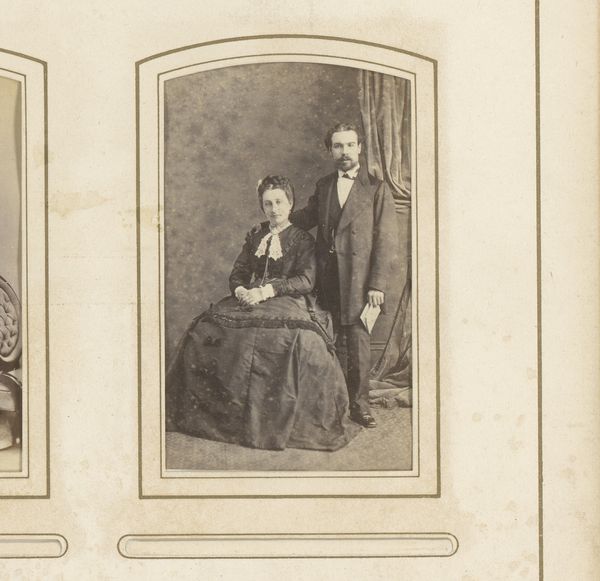

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: 383 × 545 mm (plate); 504 × 649 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

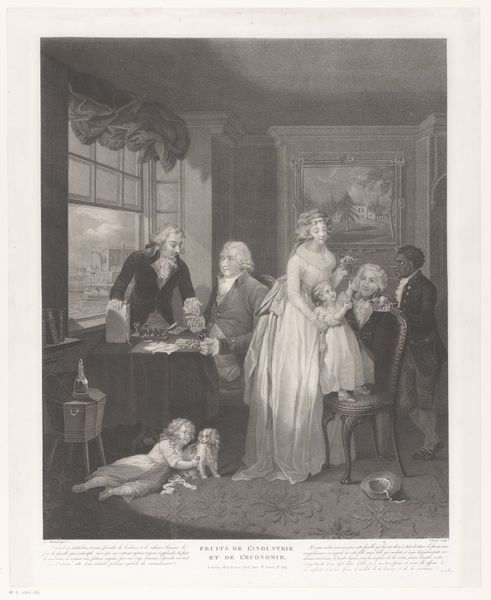

Curator: This is John C. McRae's "The Courtship of Washington," an engraving from 1860 now held at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: The stark contrasts immediately strike me, especially in how McRae models the figures with such crisp light and shadow. It creates an intimate, almost theatrical scene. Curator: The engraving depicts George Washington's courtship of Martha Dandridge Custis, later Martha Washington. But, you know, it’s important to remember these images served to create a certain kind of narrative. Courtship as refined, almost aristocratic. Editor: Indeed. Note the way McRae uses line and texture to distinguish surfaces—the delicate lace of Martha's dress, the smooth wood of the chair. These elements build a sense of depth, inviting the viewer into this domestic tableau. Also note how McRae subtly framed Martha Dandridge Custis, so Washington could be her true equal, and someone like Washington could come and fill a sort of absence left by Custis' late husband. Curator: This print participates in a broader 19th-century fascination with creating visual histories, cementing narratives that favored particular social ideals. Think of how genre and historical painting supported national myths. It's as if they wanted to write the origin stories as they happened, giving a kind of symbolic elevation, if you know what I mean. Editor: The engraver also plays with scale quite subtly. While Washington occupies a full quarter of the composition on the right, the women share the remainder of the plane together. McRae wanted us to draw some connection with gender relations. But what a fascinating choice, overall, to set history in what amounts to a domestic interior, however luxurious. Curator: Considering the circulation of these kinds of prints at the time, it underscores the power of imagery in shaping public memory, then and even now. How does seeing it affect us in light of historical revisionism today? Editor: Well, thinking purely formally, it really reveals the limitations of black-and-white print in capturing a scene. We, the viewer, almost innately look at what is blacker than what is. Curator: And that helps us reflect on the impact of visual storytelling, especially the stories we choose to tell. Editor: Yes, the light and shadow show that history painting can truly be that-- light or shadow.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.