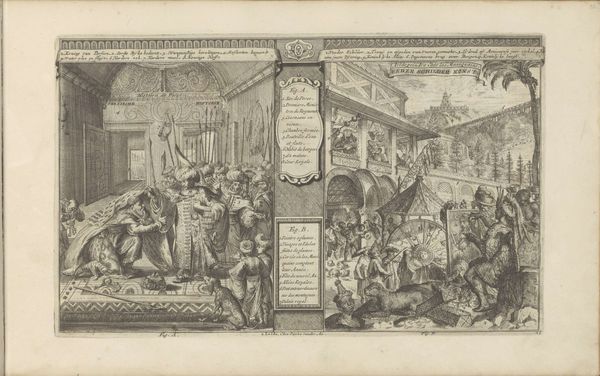

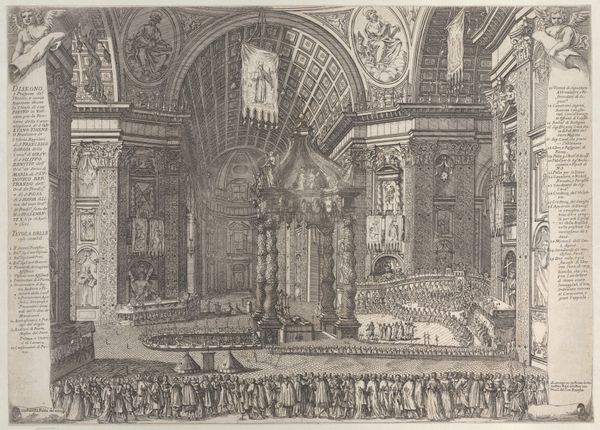

Turkse moskee in Constantinopel; Keizerlijk hof in China 1682 - 1733

0:00

0:00

romeyndehooghe

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 216 mm, width 347 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Oh, this print. It feels so... encyclopedic. Like a peek into how the world appeared to the Dutch in the late 17th century. What do you think? Editor: It’s like looking through a keyhole, isn’t it? All those tiny, precise lines—yet, I find the composition kind of disorienting, as if my perspective keeps shifting. A kind of fever dream made real through detail. Curator: Exactly! This is "Turkse moskee in Constantinopel; Keizerlijk hof in China" or "Turkish Mosque in Constantinople; Imperial Court in China," by Romeyn de Hooghe, made somewhere between 1682 and 1733. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. The engraving on paper captures these very different cultures with such intense curiosity. Editor: The way the Islamic space is depicted contrasts sharply with the Chinese court. The mosque appears vast and echoing, emphasizing spirituality and community, while the court suggests rigid hierarchy. Were these contrasts deliberate, or simply a result of limited information? Curator: De Hooghe likely relied on second-hand accounts, shaping his portrayals based on prevailing European attitudes toward the Ottoman Empire and China. I like how the Baroque flair sneaks in; that ornamental detailing on everything...It's as though De Hooghe can’t quite see the world without dressing it up. Editor: Precisely. This Baroque "dressing up," as you call it, might inadvertently reveal more about Europe's projections and power fantasies than about Ottoman or Chinese realities. I see in that excessive ornamentation, and even the composition of the whole piece, the seeds of colonial arrogance. Curator: Perhaps! Still, I'm drawn to those little details, like the tiny figures going about their lives. They offer a kind of intimacy amid all that grandeur. Makes you wonder about their stories, doesn't it? I can imagine myself lost in a city street from a bygone era. Editor: And that is the enduring, slippery trick of art – its ability to be co-opted for so many visions, ours included, even centuries later. By pulling the past into a dialogue, though one admittedly dominated by a European gaze, maybe we come one tiny step closer to understanding. Curator: It is like holding up a cracked mirror to history... the images are never quite right, but you catch unexpected reflections, insights you would never get staring straight ahead. Editor: Exactly. Each mark becomes not just representation, but also testimony. Food for thought, I suppose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.