silver, glass, sculpture

#

silver

#

baroque

#

glass

#

sculpture

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: Overall (cruet frame .184a, b): 3 5/8 × 6 1/2 × 11 in. (9.2 × 16.5 × 27.9 cm); Height (cruet with stopper .184c, d): 8 in. (20.3 cm); Height (cruet with stopper .184e, f): 8 in. (20.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

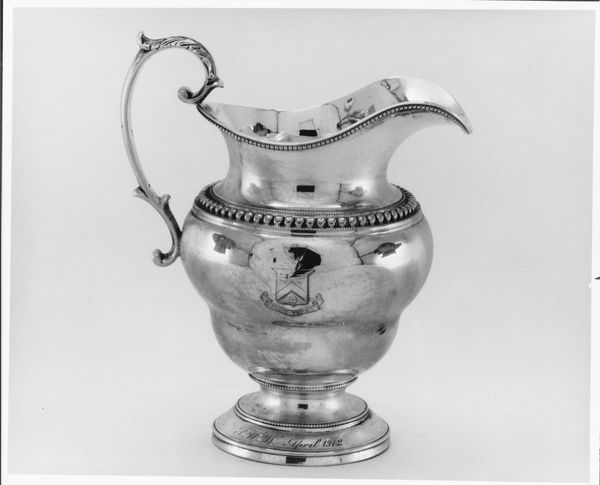

Curator: At first glance, I’m struck by the level of craftsmanship – the silverwork is so ornate, particularly around the base, but the translucence of the glass also beckons a closer look. Editor: And that is just what it demands! What we have here is a cruet frame with later glass bottles, made by Richard Jarry in London between 1717 and 1722. It is a baroque decorative artwork currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum. It consists of a silver frame and two glass bottles, a fine example of early 18th-century dining accoutrements. Curator: I find myself wondering about the process – hammering the silver, blowing the glass. The glass bottles aren’t uniform, it speaks of the hand and breath shaping the piece. It begs the question: who was consuming from these, and under what social rituals? Editor: Absolutely. These cruets were intended for affluent households, as markers of refinement. It reflected not just wealth but participation in specific social performances – how one presented and consumed these oils and vinegars became performative aspects of high status in eighteenth century dining. Curator: Right. So the elaborate decoration isn't purely aesthetic. Each detail – the scrolled handles, the cast head centered in the design – represents access to specialized labour and control over material resources, signifying power through production. Editor: Precisely! Think about the institutions that fostered this art – the guilds that controlled craft standards, the workshops where artisans like Richard Jarry honed their skills, and the wealthy patrons who drove demand for luxurious items like this. The Baroque style itself promoted grandeur and display of power. The dining rooms displaying such artworks functioned almost as theaters for the elite, further broadcasting wealth and influence through visual spectacle. Curator: It really speaks to the historical moment, when consumption itself became a visual art form. That silverwork must have demanded great skill... What narratives did owners construct when displaying the objects? Editor: Exactly, these aren't merely utilitarian objects; they embody a performance. In viewing pieces like this today, the museum plays its own role in continually negotiating its historic and contemporary values to a modern audience. Curator: It is remarkable how much of that era this object manages to tell, even centuries later. Editor: Indeed. It has transformed from a dining implement into an object steeped in social and cultural histories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.