drawing, paper, ink-on-paper, ink

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

asian-art

#

paper

#

form

#

ink-on-paper

#

ink

#

abstraction

#

china

#

line

#

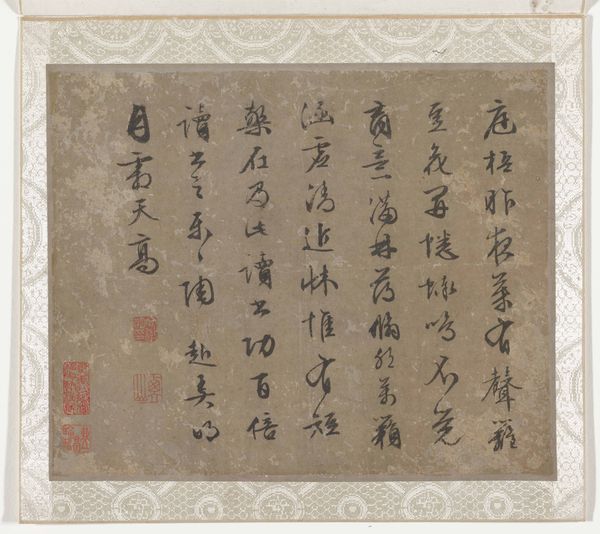

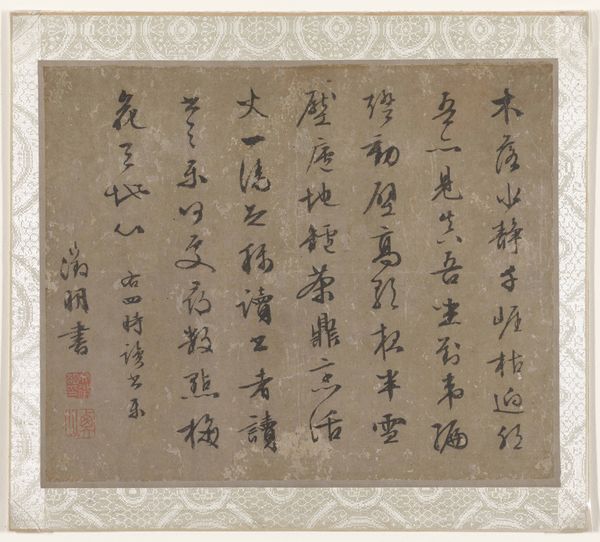

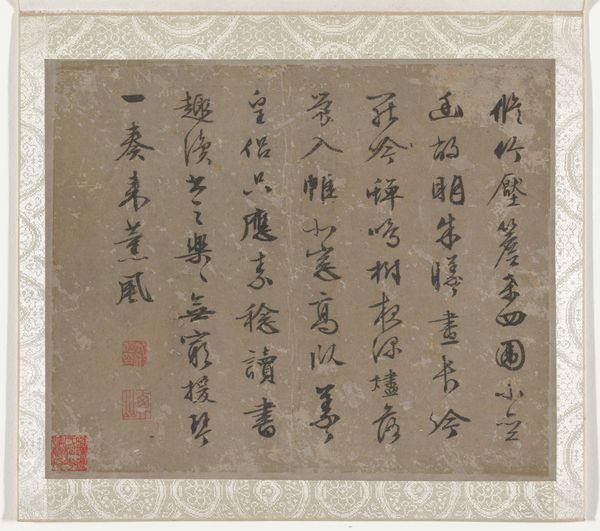

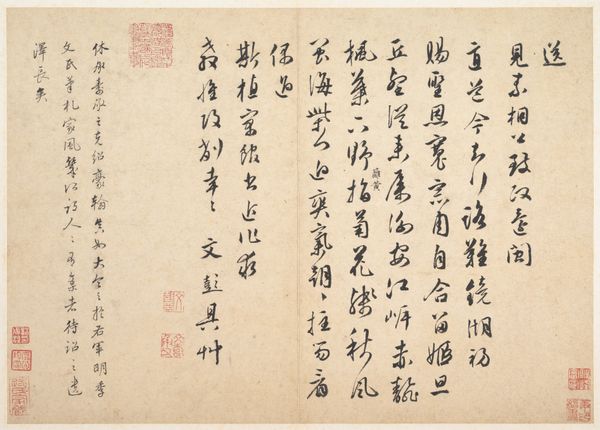

calligraphy

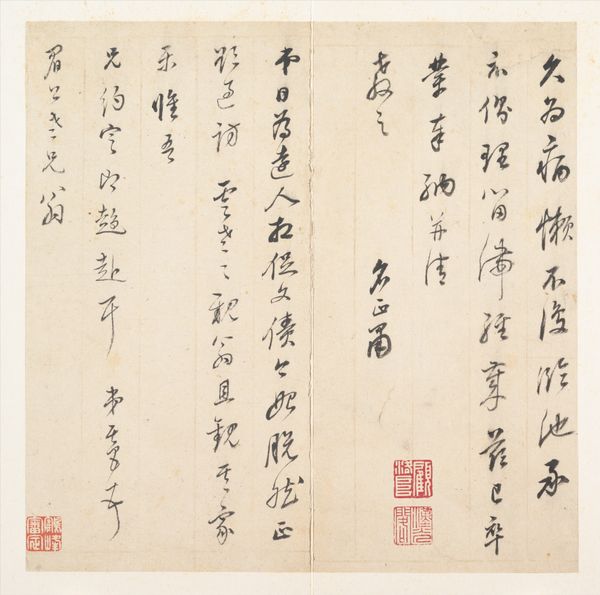

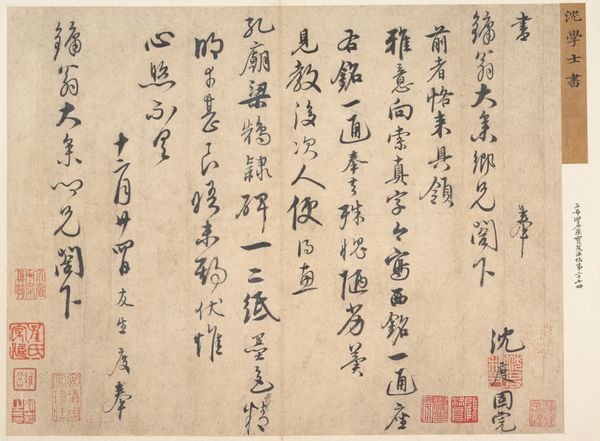

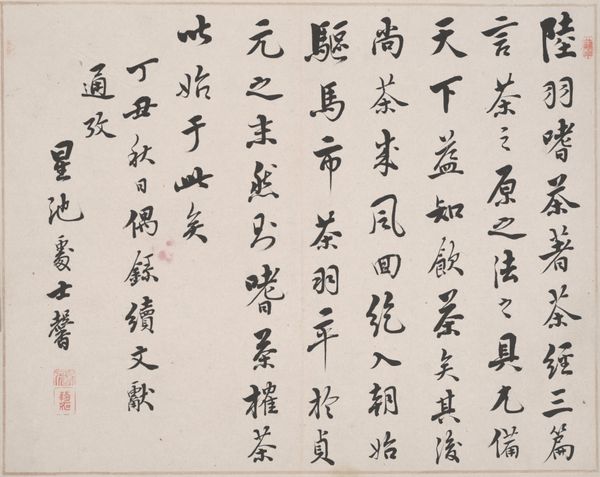

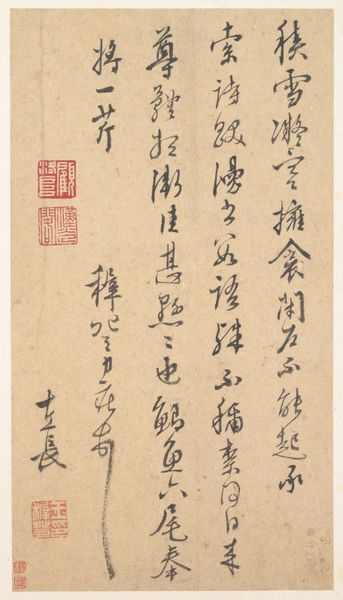

Dimensions: 10 1/4 × 12 1/4 in. (26.04 × 31.12 cm) (image)12 3/4 × 14 1/4 in. (32.39 × 36.2 cm) (mount, bottom half of mount, from fold downward)

Copyright: Public Domain

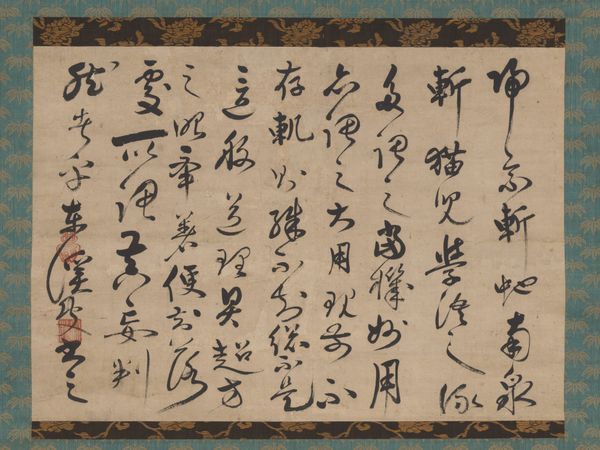

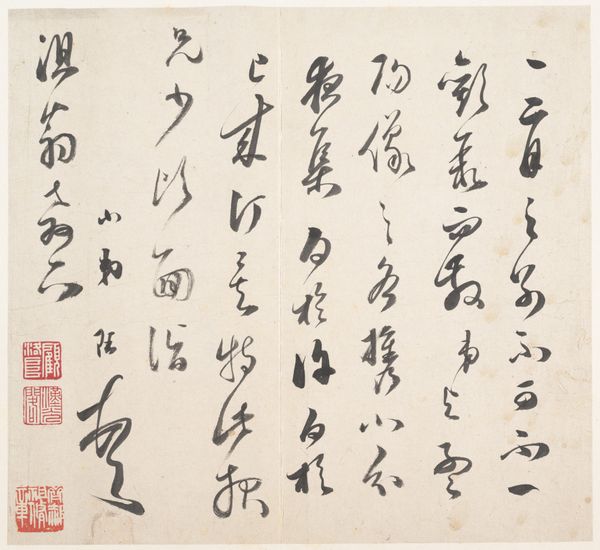

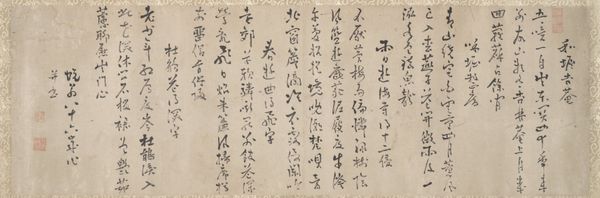

Curator: Standing before us is a piece of calligraphy from around the 16th century, "Weng Sen's Poem in Running Script," attributed to Wen Zhengming. It's ink on paper, residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: The energy of this piece is so vibrant. It feels like the characters are dancing, almost playfully arranged across the toned paper. It invites your eye to follow this beautiful rhythm across the piece. Curator: Wen Zhengming was, of course, a leading Ming dynasty artist, deeply involved in the literati culture. Calligraphy, for him and his contemporaries, wasn't merely writing, but a key component of scholarly expression, connecting visual form with poetic content. Note the choice of "running script" or semi-cursive style; that signals a degree of informality and fluidity. It is, from that view, about conveying a sense of spontaneity and personal expression. Editor: You know, looking at this piece, I imagine the artist's hand, the pressure and release as they glide across the surface. The whole idea of labor in art creation is front and center, to me at least, the way a connection between mind, body, and the materiality of ink becomes quite spiritual. Curator: Absolutely. We see, through pieces like these, how artistic creation during the Ming Dynasty, the role of artisans was often intertwined with scholarship and elite society. By closely observing the materials of the brush and ink on paper, one can uncover a depth of art production, even from something that may appear to be a writing exercise. Editor: I’m finding the idea of spontaneity so liberating. And it is precisely in such works of art that, paradoxically, it conveys a disciplined beauty. I'm almost reminded of jazz, you know, with the freedom of improvisation sitting right on the foundations of intricate formal skills. Curator: That analogy rings true. This really underlines how the social context of the artist – in this instance, Wen Zhengming and the Ming dynasty's emphasis on scholarship and artistic proficiency - has implications and resonance when understanding Chinese calligraphy as not just a formal style, but a visual, emotive form of poetry. Editor: Yes, the balance and rhythm is really captivating. I'm thinking about how much a material thing can speak so profoundly about ephemeral matters like freedom, tradition and self expression. Curator: Indeed. By viewing it with that lens, a new dimension comes alive within these strokes and patterns. Editor: A wonderful connection to take away!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

During the Ming period, members of the elite who gained fame for their calligraphy were often equally famous for their achievements in painting. Within elite society, calligraphy was equally admired as painting. It was viewed as quintessential yet functional, rather than as merely an independent visual art form or means of self-expression and cultivation. Many artists in the Ming dynasty were not only good at painting, but also excelled in composing poems and calligraphy. These three arts are known as the sanjue, or the “Three Perfections.” Both Wen Zhengming and Zhu Yunming are regarded as great masters with skills of the “Three Perfections.”

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.