sculpture

#

conceptual-art

#

minimalism

#

form

#

geometric

#

sculpture

#

abstraction

#

line

#

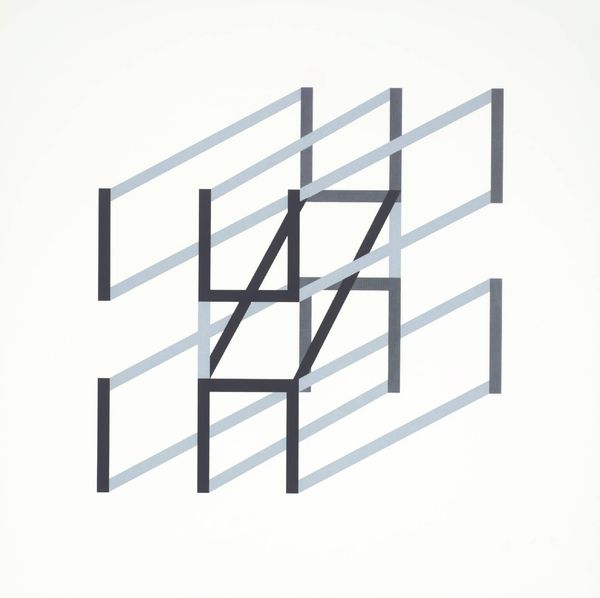

architecture render

#

modernism

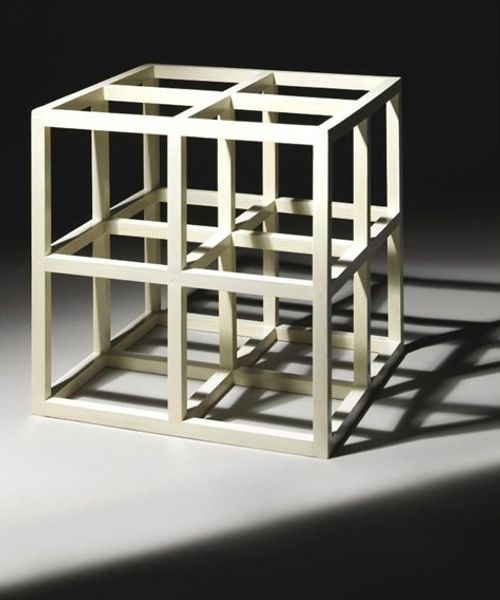

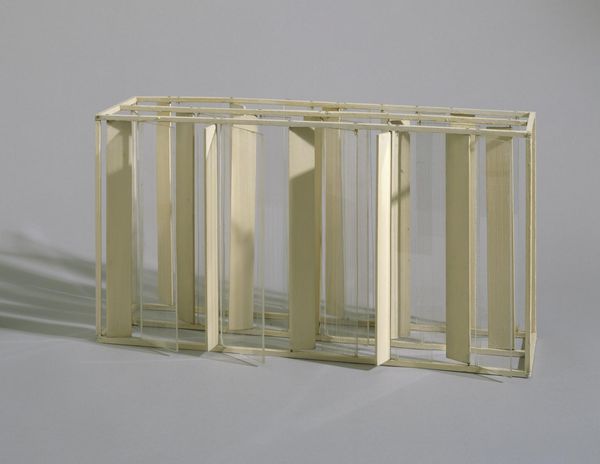

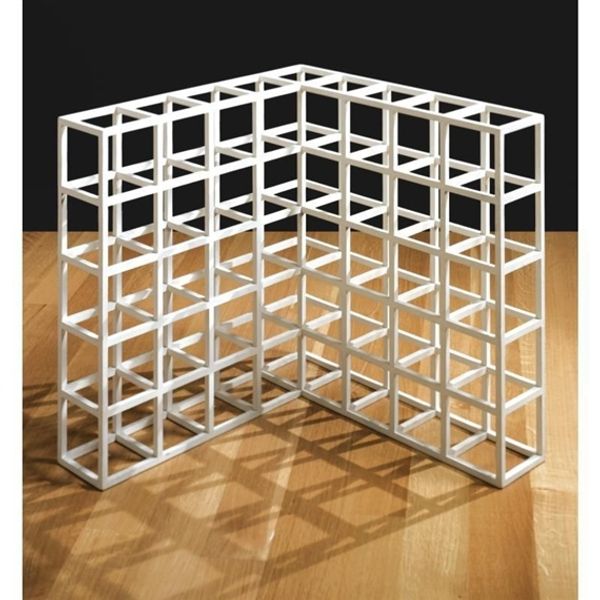

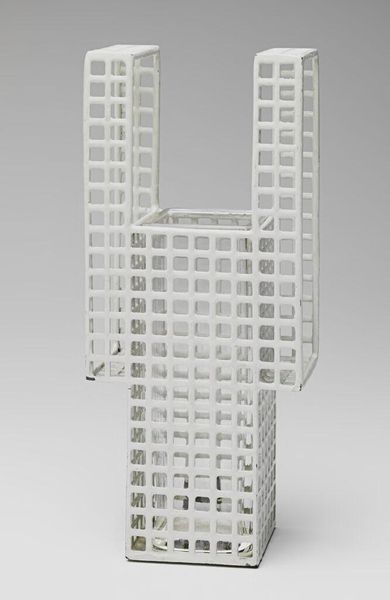

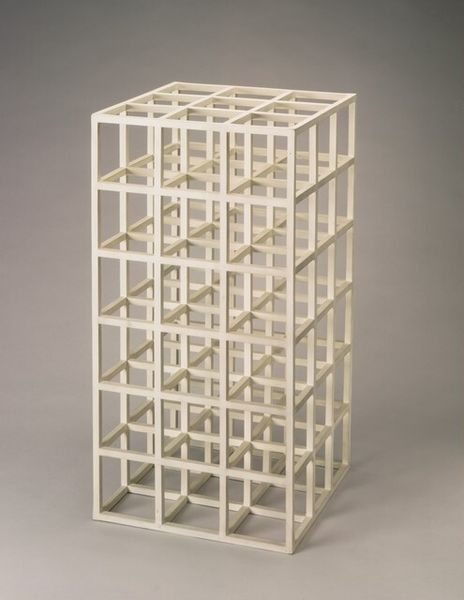

Dimensions: overall: 13.3 x 37.7 x 37.7 cm (5 1/4 x 14 13/16 x 14 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: We’re looking at Sol LeWitt’s “1 3 1 (5 Unit Cross),” created in 1971. It's a painted wood sculpture. What's your initial impression? Editor: Well, I immediately notice the stark geometry, of course. It has this ethereal, almost blueprint-like quality, especially with that pale finish. It feels so precise and, I suppose, quite cool and cerebral. Curator: LeWitt was very interested in reducing the artist's hand, prioritizing the concept over the execution. The grid, the modular units—they were meant to be easily replicable. What do you think about that level of depersonalization? Editor: That makes me think about the role of art institutions and their engagement with such "democratic" artistic endeavors. Was this meant to be a challenge to the art market itself, or was it inevitably co-opted by it? LeWitt's instructions become the artwork's script. But who gets to interpret that script? The institutions, right? Curator: Indeed, and that interpretation involves tangible decisions regarding fabrication. Consider the labour involved: the choice of wood, the painting, the assembling of units. There’s still a very real physicality to the process, even as the idea is paramount. Also, remember that minimalist sculptures like these moved into the gallery space challenging pre-existing display norms. Editor: Absolutely. Its relationship with architecture cannot be denied. These lines create their own structural ecosystem. Where and how a piece like this is displayed informs its purpose within that defined location, no? It may exist as mere ornament if installed improperly. The piece needs to feel essential and crucial to be effective as anything beyond basic visual intrigue. Curator: And LeWitt’s use of common materials really opens up this sculpture's relationship to production methods of that era and its critique of formal sculpture. We’re compelled to think about the socio-economic elements related to its material status and construction, like considering which studio may have supported him. Editor: Exactly. Considering it was created in the seventies during times of great social change it represents the socio-economic struggles artists of the period faced in relation to creating politically relevant material for their viewerships. The piece embodies an interesting intersection of high concept, democratic impulse, and concrete production. Curator: Thank you. That was illuminating! Editor: Thanks to you as well. Always something new to consider.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.