Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

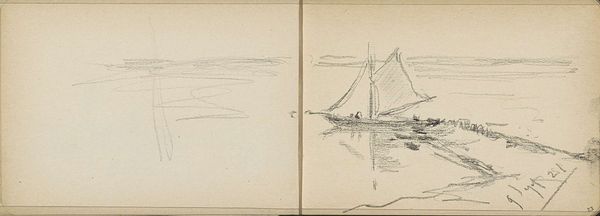

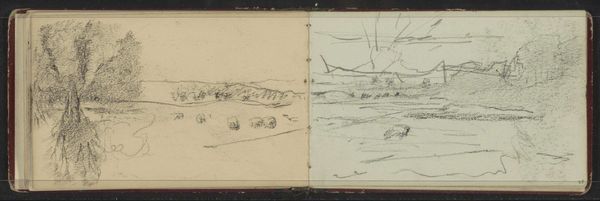

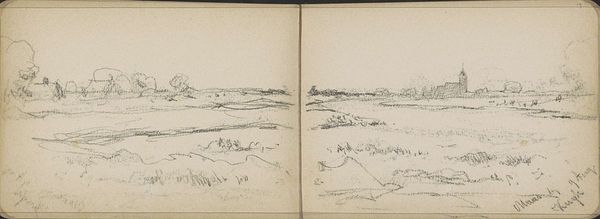

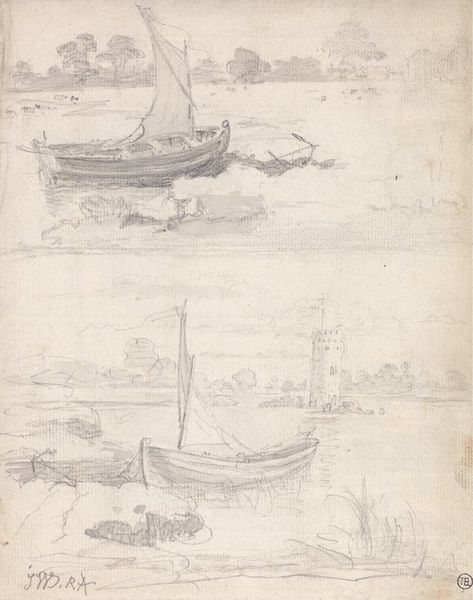

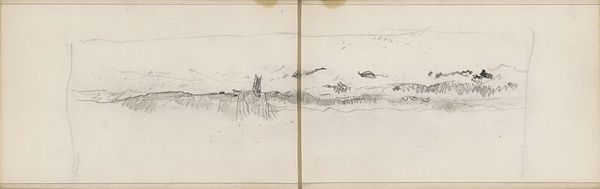

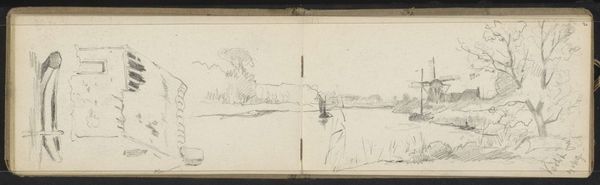

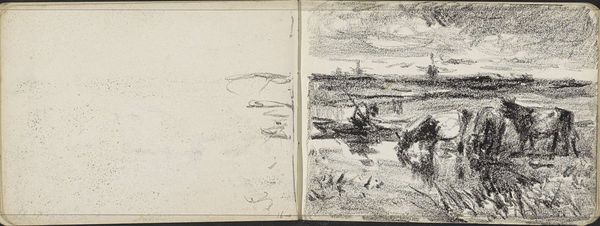

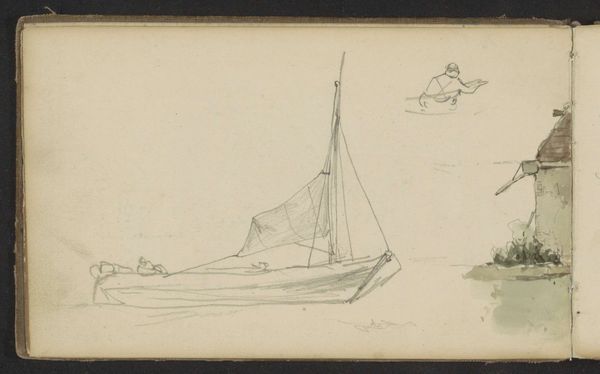

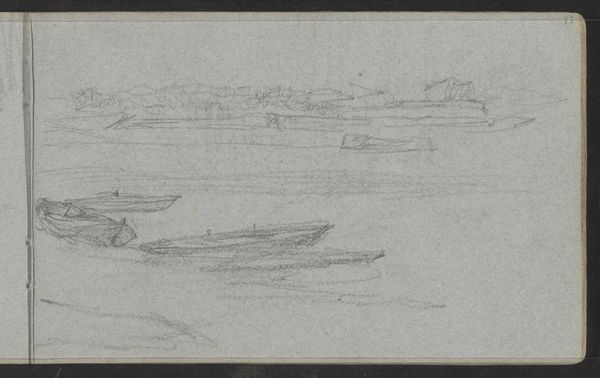

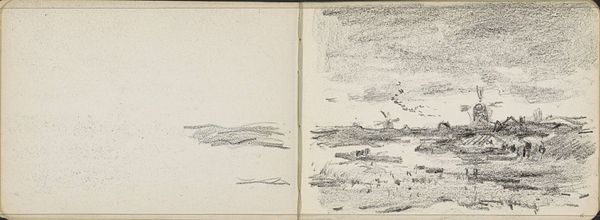

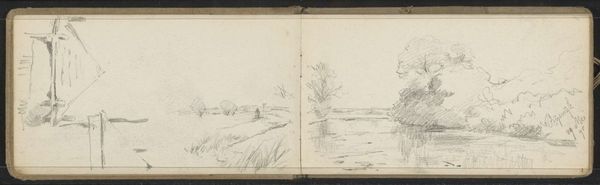

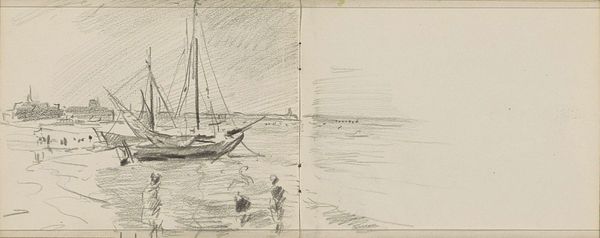

Curator: This pen and pencil drawing, titled "Zeilschepen, mannenkoppen en een landschap" which translates to "Sailboats, male heads, and a landscape", dates back to 1864 and is by Johannes Tavenraat. It's part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It strikes me as such an intimate glimpse into the artist’s process – like opening up their personal sketchbook. There's something really raw about the seemingly random placement of subject matter, especially considering its relatively large size, 23.5 cm x 47.4 cm. Curator: Exactly. Think of the artist at work; his choices regarding materials reflect on artistic expression beyond the established hierarchies. The availability and cost of drawing supplies like pen and pencil during the 19th century democratized the act of creation, moving away from a reliance only on wealthy patrons who financed expensive oil paints and large canvases. Sketchbooks represented more accessible artistic labor. Editor: That really changes the narrative, doesn't it? Rather than viewing the artist as some isolated genius, we can contextualize this work in terms of access, material culture, and how that accessibility may affect his subject choice: ordinary citizens of the day portrayed alongside local landscapes and scenes of labour or leisure in sailing and farming. Curator: Absolutely. We see this Romantic and Realist duality really shining through with the detailed human studies beside landscapes of labor—consider the subtle inclusion of social commentary, capturing everyday realities beyond the scope of heroic painting. The act of placing working figures next to peaceful pastureland is an intentional act. Editor: You are correct. I'm also intrigued by the blend of seemingly disparate studies and the notes within this page. It raises questions about the nature of artistic study in the mid-19th century. Was Tavenraat trying to create the final piece in situ or preparing for a much larger painting? Curator: Most likely the latter! Artists often compile references on paper, refining techniques before engaging larger scale artistic endeavors. Consider then the influence of Dutch painting tradition through social expectation. Tavenraat may have chosen pencil-and-paper as a means for rapidly building source imagery and practicing observation, before spending more time creating larger paintings to be shown in established Dutch exhibitions. Editor: A fascinating contrast. The loose composition conveys intimacy and speed in contrast with what must be dozens if not hundreds of hours of training it took him to render these images so swiftly. The act of observing everyday working people elevates labor to artistry in the wider sociopolitical world, making this piece a cultural landmark. Curator: Agreed. Looking closer at pieces such as this, we uncover layers within the history of art production, public consumption, and cultural values reflected throughout Dutch art as an entire discipline.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.