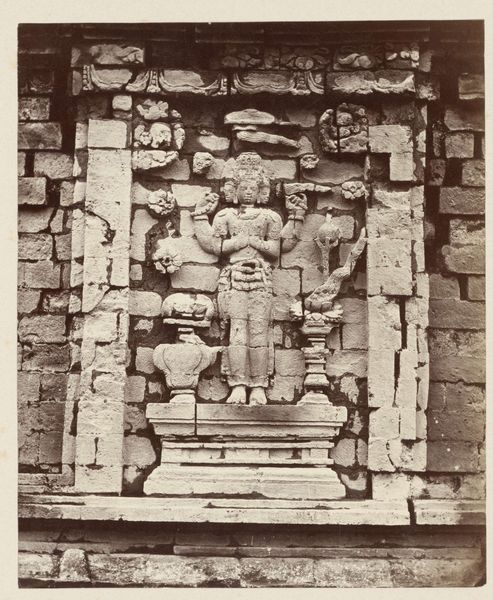

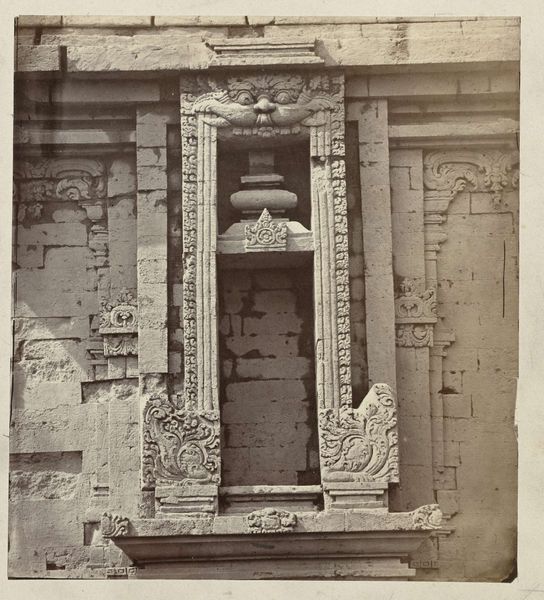

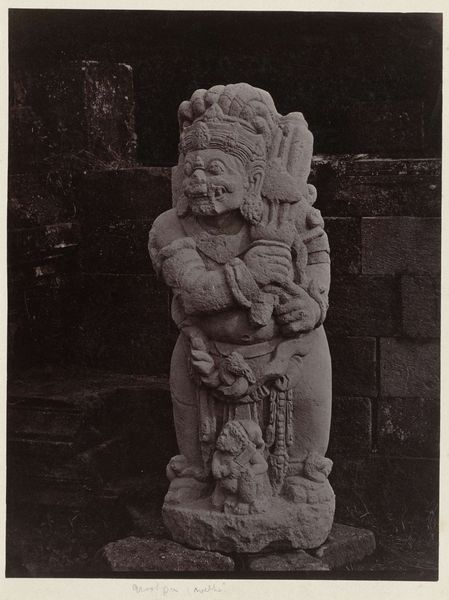

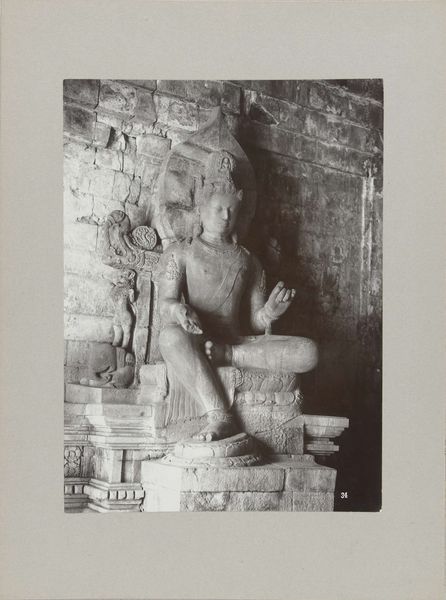

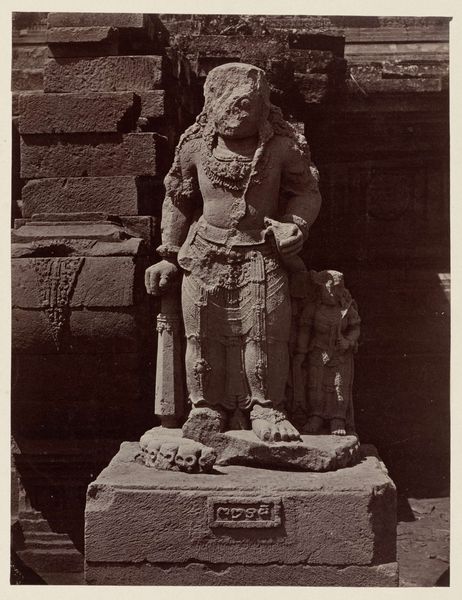

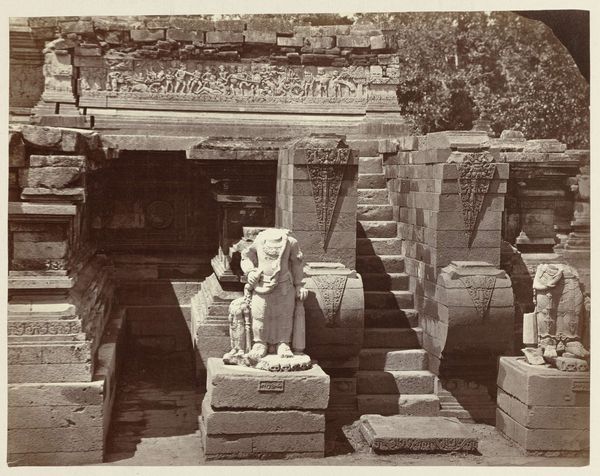

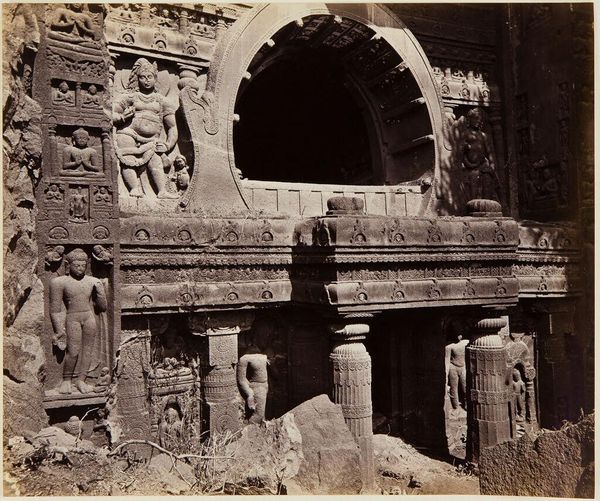

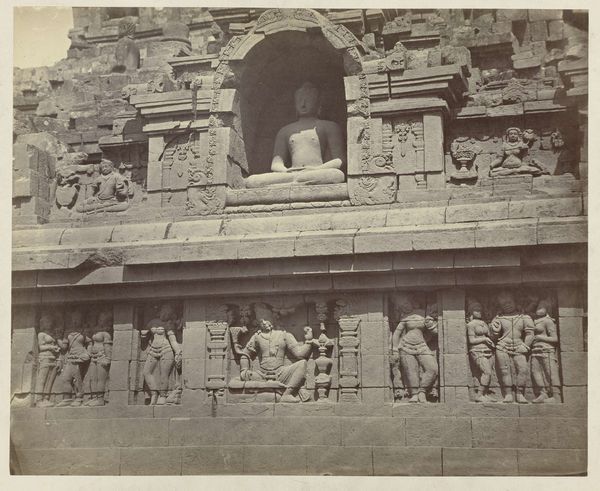

Candi Srikandi, details of the northern niche decorated with a four-armed Vishnu. Dieng Plateau, Wonosobo District, Central Java province, 8th-9th century Indonesia Possibly 1864 - 1867

0:00

0:00

carving, photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

carving

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 183 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

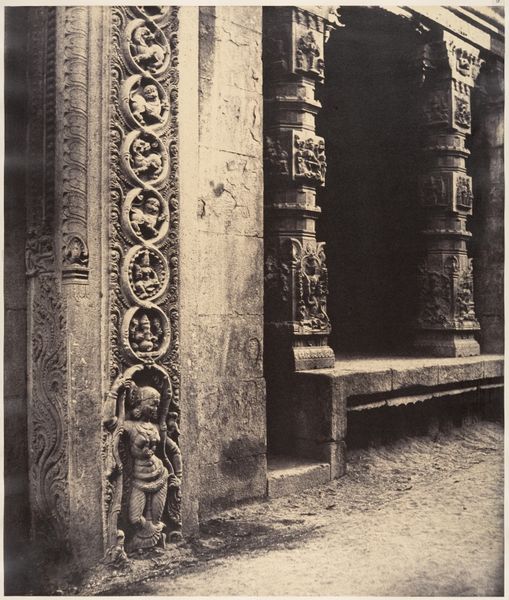

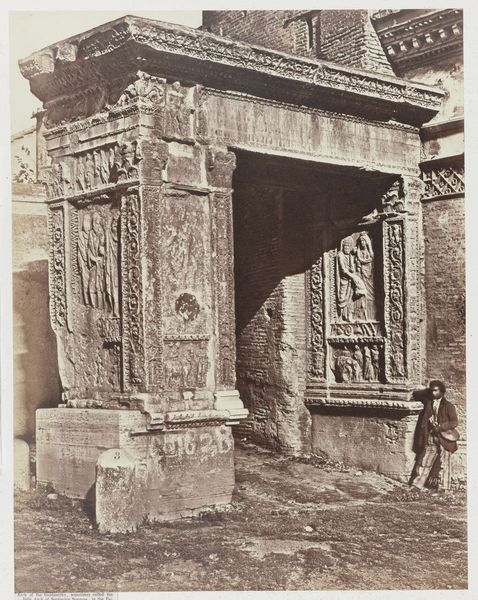

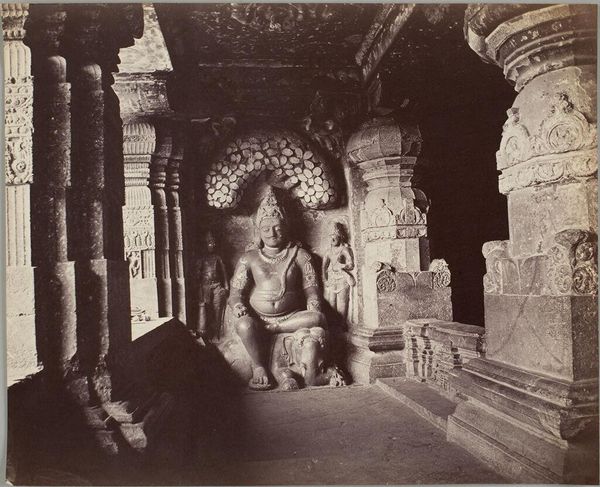

Curator: The texture is really grabbing me; I can practically feel the weathered stone. Editor: Let’s delve into this image by Isidore Kinsbergen. It’s a photograph, a gelatin silver print dating roughly from 1864 to 1867. The photograph documents a detailed carving of Vishnu from the Candi Srikandi temple, part of the Dieng Plateau complex in Central Java, Indonesia, dating from the 8th to 9th century. Curator: The linear progression here is just incredible. The composition uses this incredible interplay between the sculptural form and architectural setting—there’s such harmony in how the image marries the spiritual and the physical, wouldn't you agree? Editor: I find myself wondering about the social and economic context of both the temple's creation and Kinsbergen's photographic process. The carving is fascinating—four-armed Vishnu situated in this northern niche—but I want to know about the labor, the belief systems, and the political powers that facilitated its existence and documentation. How does the act of photographing it impact or alter its original meaning and use? Curator: Setting aside the socio-historical implications for a moment, consider the interplay of light and shadow that creates depth, defining Vishnu’s form, bringing the relief to life. This emphasis showcases classical artistic notions of idealization. Editor: Sure, but to view this solely through a lens of idealization risks missing the ways in which the image intersects with trade routes, religious conversions, or colonial endeavors that defined the area and the photographer's presence there. Were the carvers paid fairly? How were the raw materials obtained? It's also imperative to remember how photography could reframe cultural narratives in the colonial mindset. Curator: Of course, such cultural forces must always be remembered in interpreting artifacts of historical origin. I believe though, one need not forego the aesthetic pleasures to fully interpret it in materialist terms. Editor: Agreed! These dialogues can illuminate greater perspectives on such treasures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.