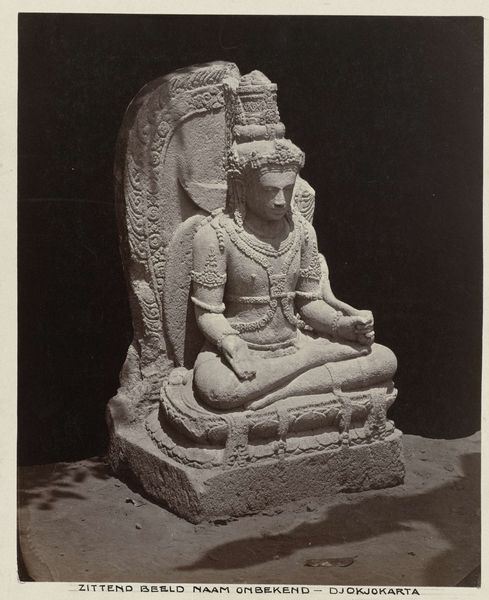

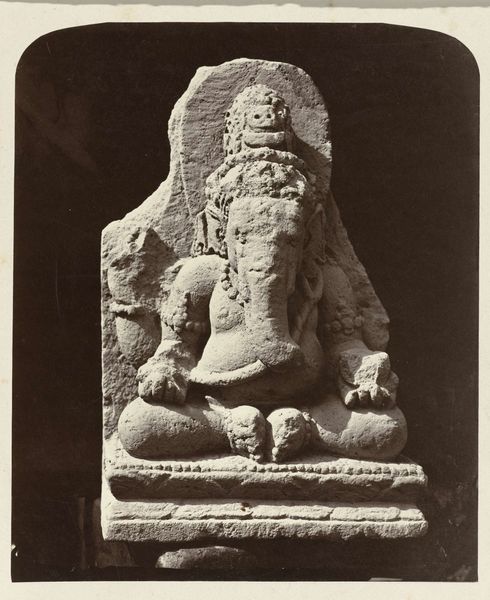

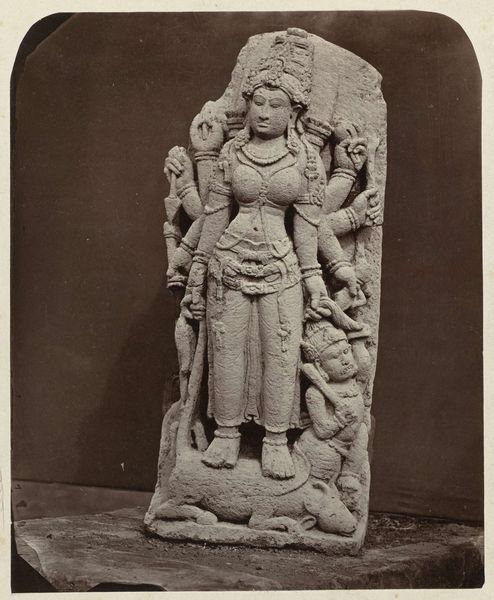

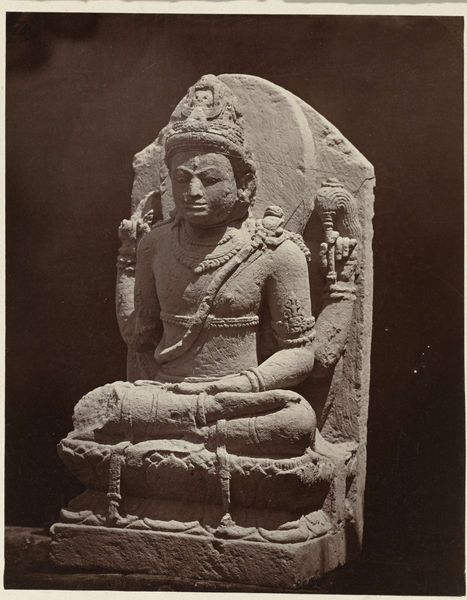

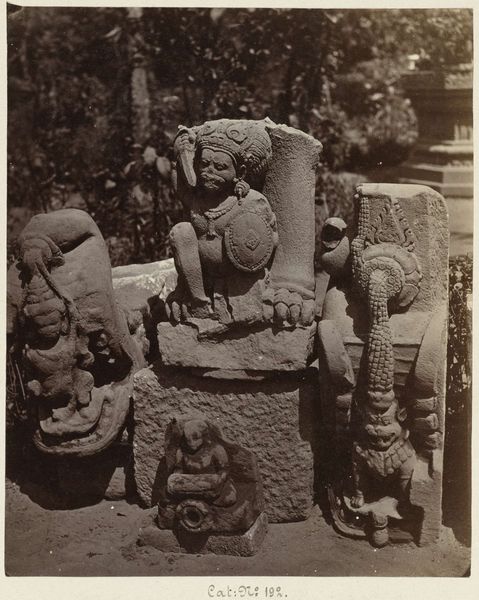

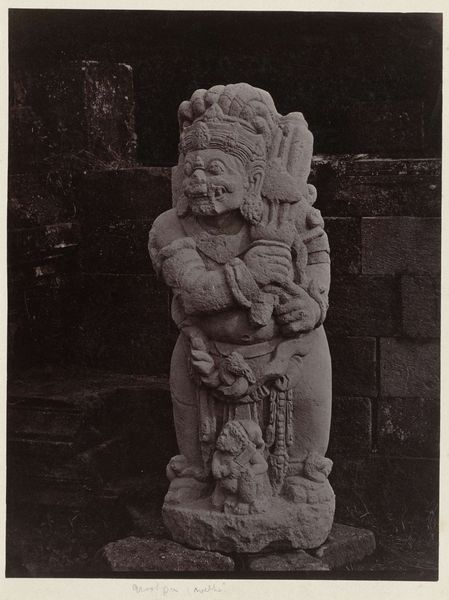

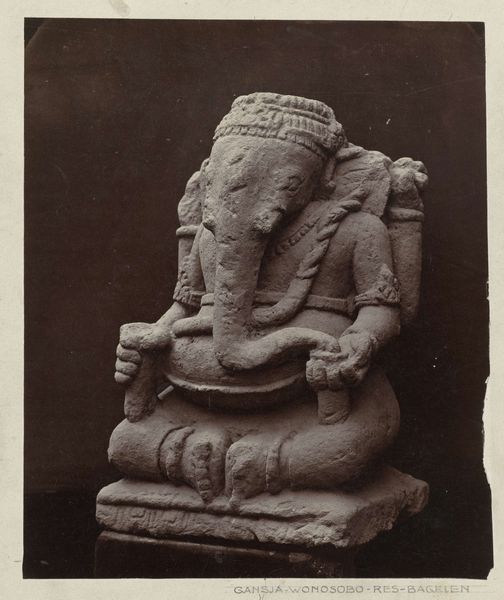

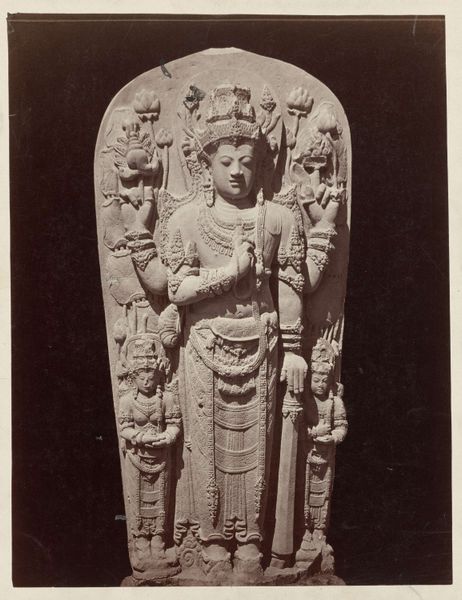

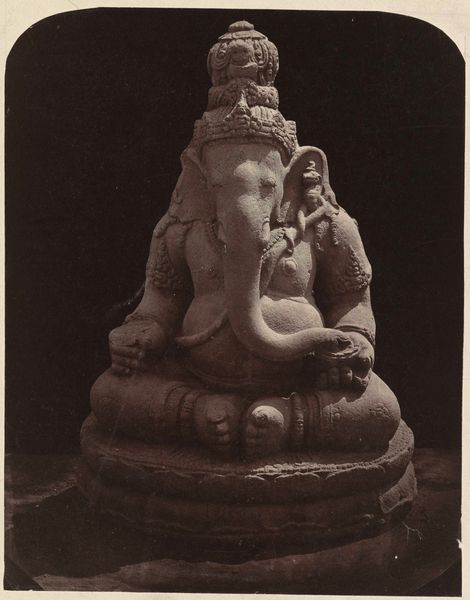

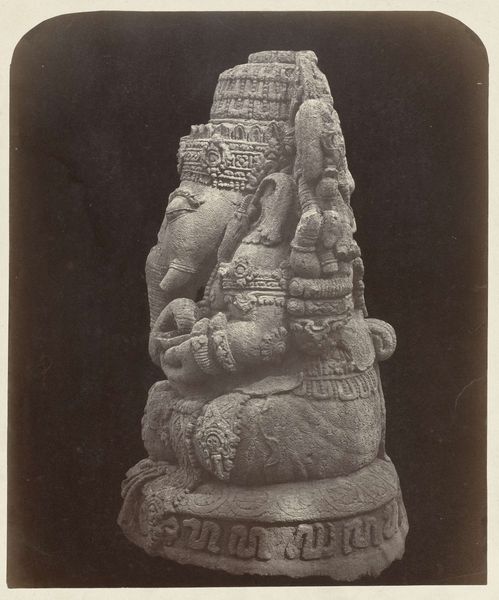

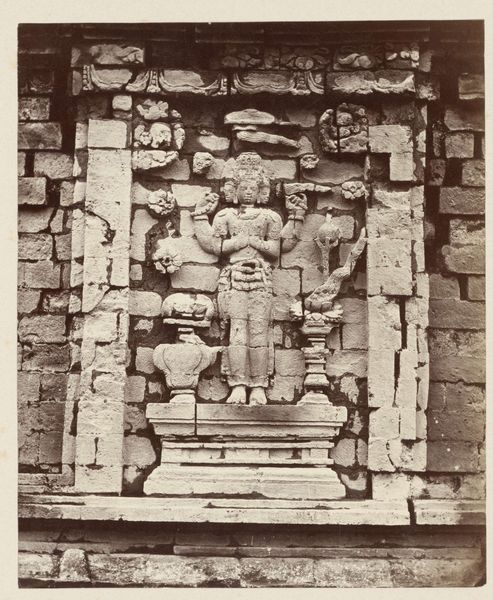

Candi Panataran (Temple Complex), Main Temple; dated dvarapala (with female attendant) guarding the left staircase, Panataran, Blitar district, East Java province, 1323-1347 AD, Indonesia Possibly 1867

0:00

0:00

tempera, bronze, photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

statue

#

tempera

#

asian-art

#

bronze

#

figuration

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

unrealistic statue

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

statue

Dimensions: height 274 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a photograph taken possibly in 1867 by Isidore Kinsbergen. The image captures the Main Temple at Candi Panataran, focusing on a dvarapala—a guardian statue—flanked by a female attendant. These sculptures date back to 1323-1347 AD and stand guard at the temple complex in East Java. Editor: Immediately, the photograph feels burdened, heavy. The stonework is imposing and looks incredibly weathered, especially the primary figure who is significantly damaged and almost looks like he’s weeping. The skulls decorating his feet send a clear message about power, mortality, and the role of a guardian. Curator: The image's historical significance lies not only in documenting the temple but also in Kinsbergen's role as one of the first photographers to extensively document the Dutch East Indies. He helped craft a specific vision of the region. His images became part of colonial displays. Editor: It’s interesting to think about photography as a colonial tool. How this image might have been used to convey the exotic, to reinforce a narrative of power and ownership over a distant and ancient culture. It really does become a political act when reframed through that lens. Curator: Indeed. We have to remember how the colonial gaze impacted representation, which is a relevant consideration when discussing ancient Javanese sculpture through the eyes of a 19th-century European photographer. Look, however, at the detail still visible. Editor: And those details do provide access points, right? We see an ornate headdress, an intricate necklace; despite the damage, there's still a visible sense of regal ornamentation, hinting at the complex hierarchies and spiritual beliefs interwoven into the temple's creation. It's also an invitation to interrogate who the attendant is: the sculpture reveals she has equal significance and stature in this sacred place. Curator: The gelatin-silver print itself enhances the feeling you describe, I think, doesn’t it? It evokes a stark realism, but at the same time—like all photographs—offers only a carefully constructed fragment. Editor: I agree. Thinking about the work photographically also begs the question of erasure, given the state of the dvarapala’s head; maybe that becomes a starting point to examine ideas around lost cultural heritage, acts of destruction both deliberate and incidental, and the responsibility that we bear now. Curator: The photo compels us to really question preservation ethics, doesn't it? Also, consider the complexities around image appropriation from former colonies. This work opens multiple important historical and sociopolitical conversations. Editor: It's more than a record; it’s an invitation to dismantle the layers of colonial storytelling. That's how we start to fully embrace this place’s deep and dynamic legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.