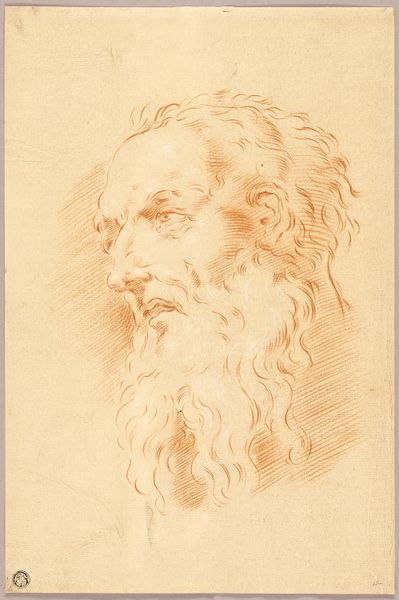

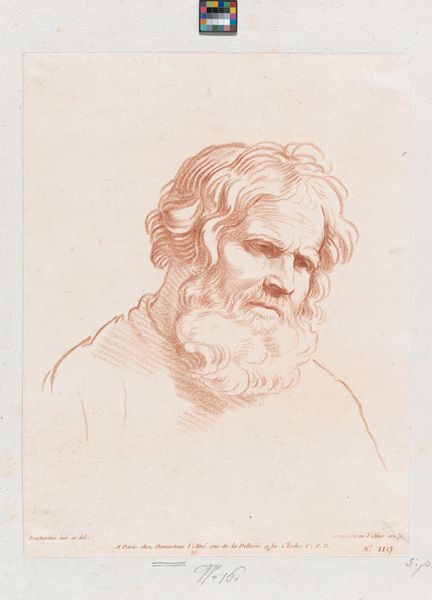

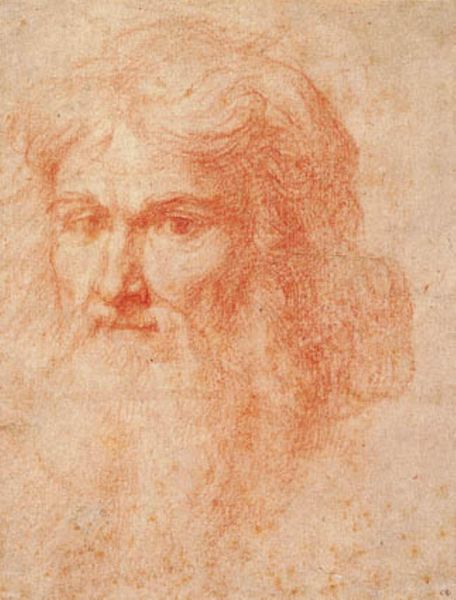

drawing, red-chalk

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

high-renaissance

#

red-chalk

#

13_16th-century

#

portrait drawing

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This drawing is attributed to Parmigianino, dating from around 1523 to 1525. It's titled "Head of a Bearded Man, looking right," rendered in red chalk, and currently held at the Städel Museum. Editor: The immediate impression is one of melancholy. There’s a quietude and weight in the downward gaze of the man, an air of contemplation or perhaps resignation. Curator: Parmigianino's drawings often served as studies for larger paintings. It makes me think about patronage during this period, particularly within the Church. A face like this might have been used for any number of saints or prophets commissioned to fill newly decorated chapels. Editor: Yes, but consider also the iconography of the beard. It instantly connects us to ideas of wisdom, age, authority... He’s not simply a man; he’s embodying a concept, an ideal that resonated deeply within Renaissance culture, echoing images from antiquity onward. The man's hair is long, it gives a sense of the philosopher. Curator: I agree, though I also think the act of drawing itself held social significance. Portraiture, even in preparatory sketches, served as a display of status, both for the artist demonstrating their skill and for the subject whose likeness was deemed worthy of capture. Look at the precision! Editor: And notice how Parmigianino uses red chalk? It softens the lines and gives the image a warmth and approachability that contrasts with, say, the cooler precision of pen and ink. He's invoking a humanism. He connects it with inner emotion through visual symbols. Curator: It is definitely a humanist approach but that’s largely thanks to commissions from wealthy families, like the Farnese, who influenced Parmigianino. Patrons expected not only artistic skill but also a specific reflection of their values and ideals, essentially a visual statement of their power. It’s difficult to divorce that social context from how we interpret this image today. Editor: Context and technique interweave, absolutely! What remains striking for me, though, is that the piece creates an individual portrait but connects at a deeper cultural reservoir to collective ideas of dignity, learnedness, even sorrow. That is what still gives it power after all these centuries. Curator: It certainly offers an invaluable window into artistic practices of the High Renaissance, along with all the complexities inherent in art production during that period. Editor: And reminds us how artists shape visual memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.