Copyright: Public domain

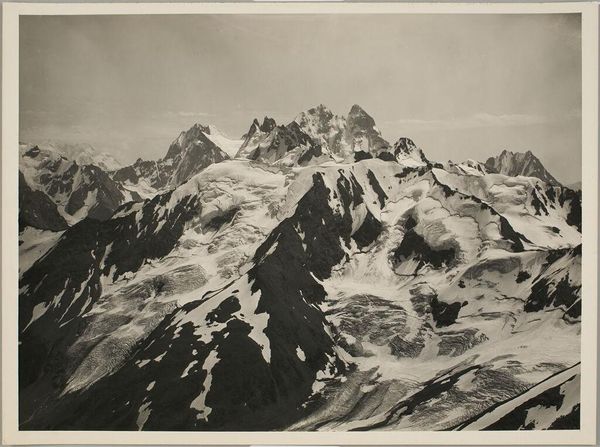

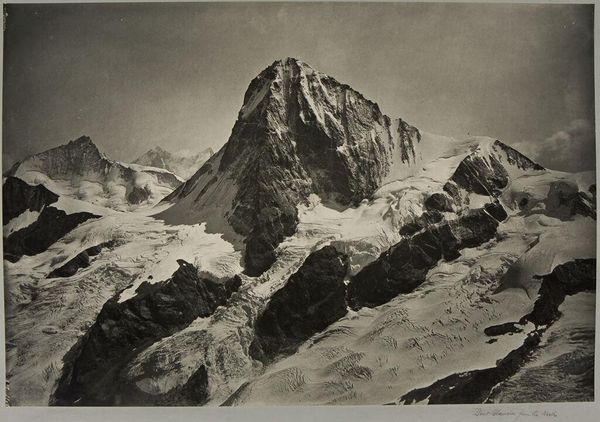

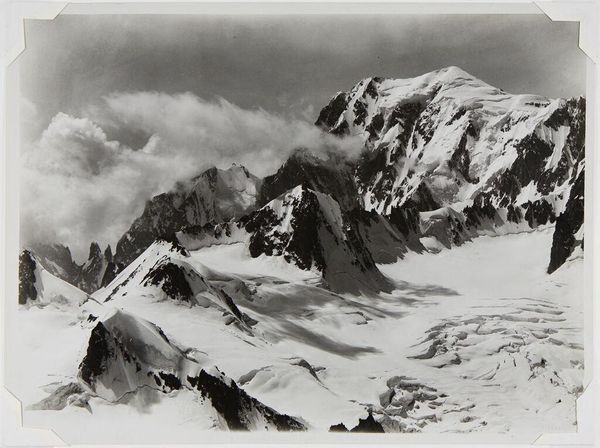

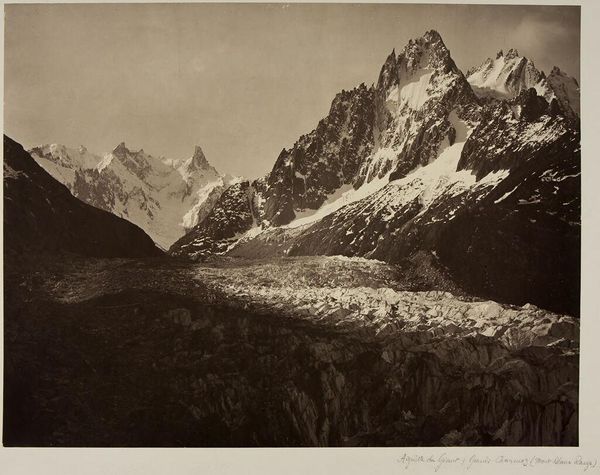

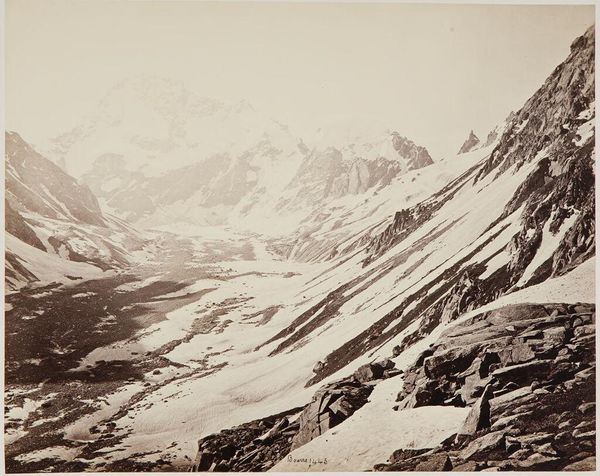

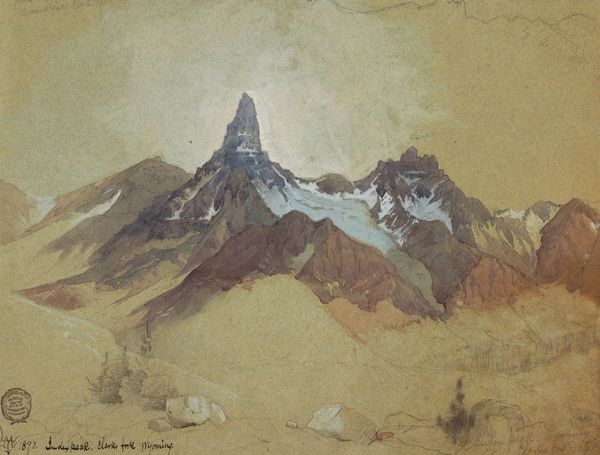

Curator: I'm immediately struck by the bleakness of this mountainscape—the monochrome palette, the sheer, jagged rock faces. It feels quite imposing, a little scary even. Editor: We’re looking at "The Aiguille Blaitiere," a drawing completed in 1856 by John Ruskin. Executed in charcoal and graphite, it exemplifies his keen observational skills and romantic sensibilities applied to the natural world. Curator: Romantic sensibilities? It’s more gothic horror to me! That stark contrast between light and shadow feels… almost oppressive. I keep thinking about class conflict during the time. Do you think industrialization and class struggles influenced the work? Editor: It's impossible to ignore those forces when considering the context. Ruskin was deeply concerned with social reform and the destructive aspects of industrialization. Mountains represented untamed nature, something pure and eternal against the backdrop of societal changes. His art becomes intertwined with that cultural context, reflecting his concerns for social justice and the environment. Curator: It definitely highlights a tension, then—between human ambition and the indifference of nature. Are we dominating the landscape, or are we utterly insignificant in its face? I think, in this particular drawing, he suggests the latter. And, I can definitely feel that pull between detail and atmosphere. Like the artist is losing himself within these mountains, yet wanting to express their sublime terror. What are your thoughts? Editor: Precisely! And that feeling is a thread we see repeatedly through Romantic art in Europe. Ruskin’s rendering is exceptionally meticulous, even scientific, in its detail, from the rock formations to the glacial striations. But it's also a grand, awe-inspiring vista, encapsulating that Romantic concept of the sublime, you’re so spot-on! That overwhelming power of nature contrasted with human frailty is hard to avoid with this drawing. Curator: I also detect this quiet undercurrent about the power of the earth's resources in both an artistic sense as well as a commodity during the Industrial Revolution. What sort of a message do you think Ruskin might have wanted to transmit with it? Editor: What message did he hope to send? It's tricky. I think he probably wanted us to reflect on our relationship with nature, the ephemeral against the permanent, while also holding it up for others to use nature itself in a means of solace or study. The mountains in this work represent more than geological formations; they embody cultural, societal, and spiritual meanings, and perhaps it would do us good to give them a moment's thought now. Curator: I find it incredibly powerful in its starkness and the questions it subtly provokes, even centuries later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.