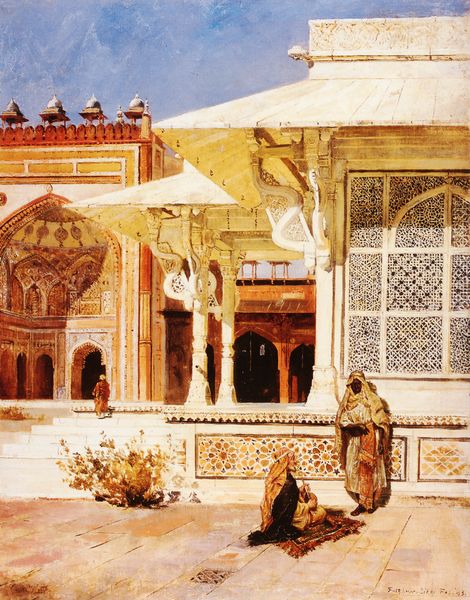

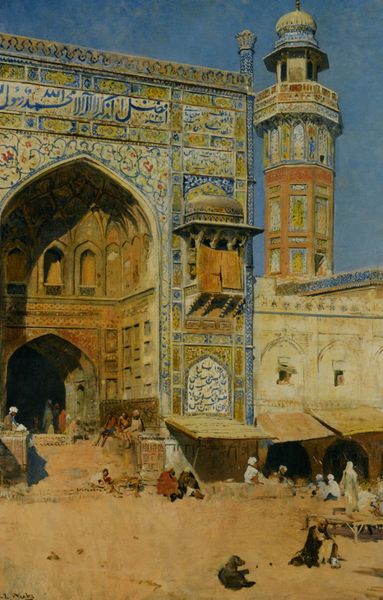

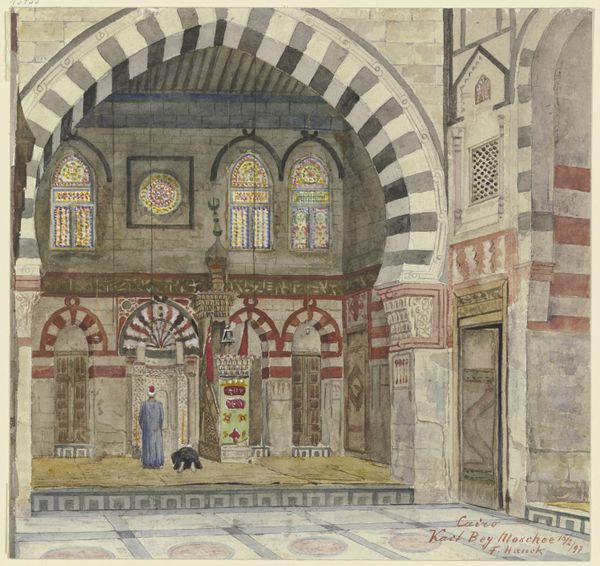

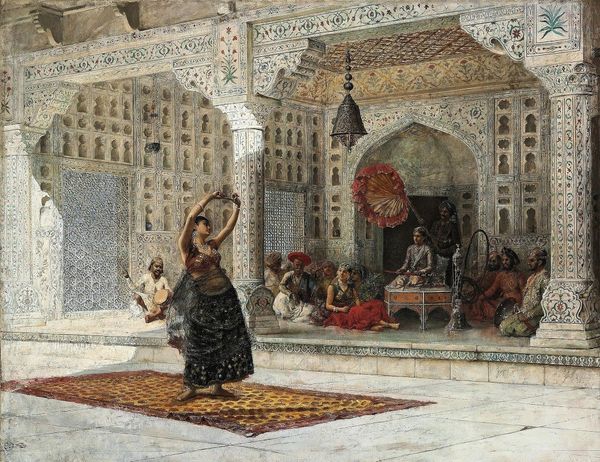

painting, watercolor, architecture

#

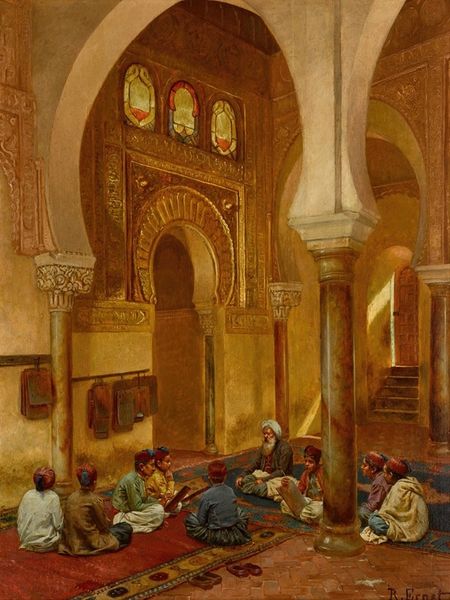

painting

#

traditional architecture

#

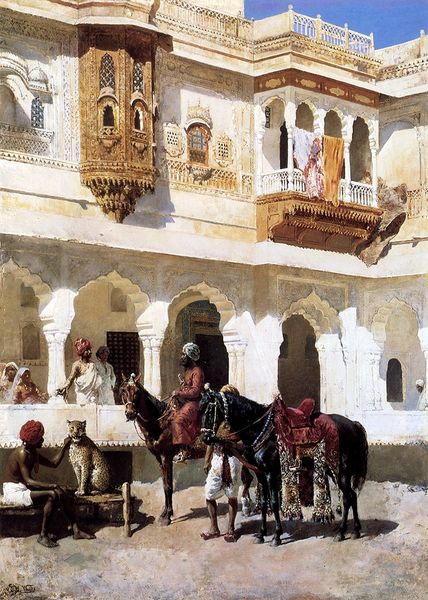

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

orientalism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

architecture

#

historical building

Copyright: Public domain

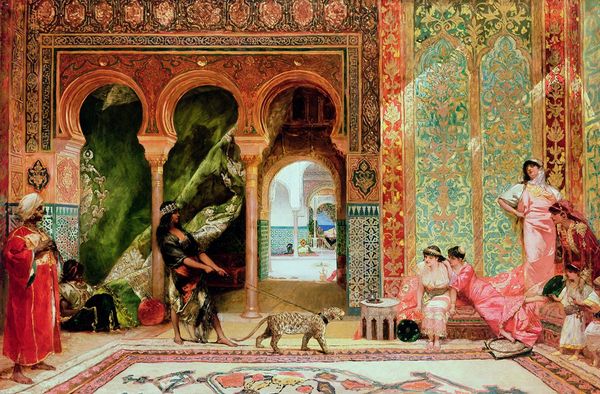

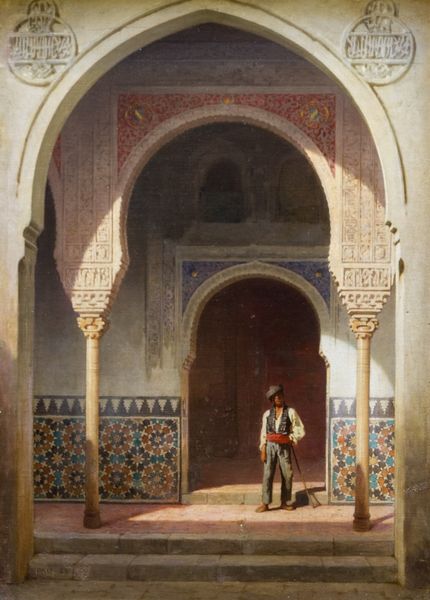

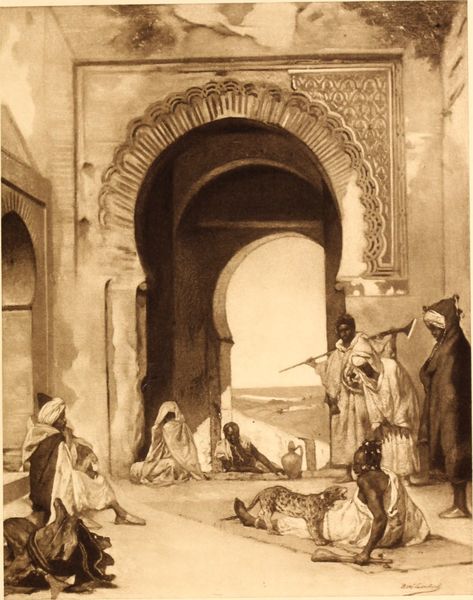

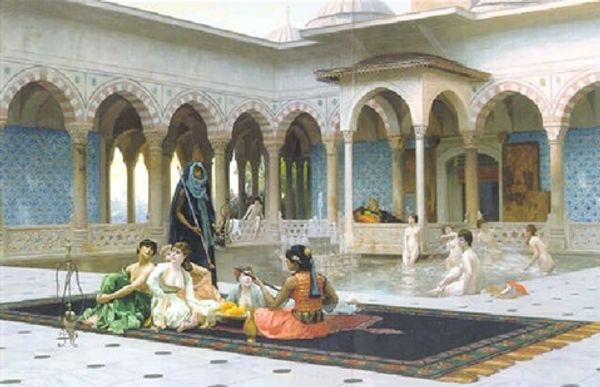

Curator: This watercolor painting, "Bazaar in Orleans", was created by Théodore Chassériau in 1849. It's a wonderful example of the artist's Orientalist period. What are your initial thoughts on it? Editor: My first impression is a sense of hushed, quiet observation. The muted palette gives the whole scene a soft, almost dreamlike quality. I find myself wondering about the unseen observer, looking onto this private world. Curator: That's a great observation. Chassériau was part of a generation grappling with France's colonial relationship with North Africa. Paintings like this need to be seen as both artistic explorations of another culture but also reflecting colonial power dynamics. Consider the gaze, who is invited to view this scene and on what terms? Editor: Exactly. The gaze is definitely mediated, a colonial encounter represented for a European audience. The figures within seem caught in a timeless space, framed and arguably ‘othered’ by the architecture and the artist’s hand. I also wonder about gender and spectatorship – how does the inclusion of women on the balcony influence the politics of the image? Curator: Chassériau's romanticism plays a huge role. He’s not presenting a documentarian’s reality, but a carefully constructed image. And let's talk about that architecture. The repeating arches, the delicate patterns. They construct a sense of order, but also confinement, framing each individual narrative within a larger, overarching structure of power and expectation. Editor: Yes, it evokes both beauty and, perhaps subconsciously, control. Looking at the specific historical moment, this image contributes to the broader Orientalist narrative, impacting how Europe perceived, and ultimately controlled, the regions it depicted. The choice of medium—watercolor—adds a layer of delicate fragility, reinforcing, maybe even sentimentalizing, the colonial perspective. Curator: Thinking about art's public role and the politics of imagery helps contextualize its original consumption. The bazaar, normally a site of trade and bustling activity, is depicted with this careful, almost studied stillness, it raises fascinating questions about artistic intent, socio-political context, and legacy. Editor: Indeed. Thinking about identity, race and colonialism provides essential frames when grappling with the work's visual vocabulary. I walk away understanding better both the aesthetic accomplishment and the layered ethical quandaries of cultural representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.